As we all know, Howard Zinn was a prominent activist under the “auspices” of Boston University, best known for hisA People’s History of the United Statesthat was popular in every sense of the word, one of the reasons for its having remainedso powerful. Understandably, on March 2, the governor of Arkansas, Kim Hendren introduced a bill to suppress the work of the great man that is being continued and advanced by the Howard Zinn Project. This organization of benign missionaries works to promote the works of Zinn among middle- and high-schoolers, in an attempt togive some balance to the history courses which take a tendentious recourse to patriotism against an emetic past.

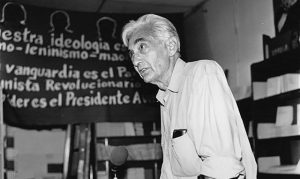

An Arkansas state representative is seeking to expunge books he doesn’t like from public school curricula — including those “by or concerning Howard Zinn.” (Photo: Slobodandimitrov / Wikipedia)

To limit access to Zinn’s work is thus an insult to the intellectual freedom and development of Arkansas students.

Hendren, confusingly, even seems to acknowledge the issues with his proposal, stating in his interview with Reason Magazine that his goal is not necessarily for the bill to be passed but rather “to start a conversation.” Perhaps for unintended reasons, Hendren has succeeded. But then it’s worth asking what he intended for the conversation to be about. If he were truly interested in sparking conversation about the alleged harms or “indoctrinating” power of Zinn’s book, he would respect the intelligence of Arkansas students and make the book (and their criticisms) available so they can be discussed and the students can come to those conclusions for themselves. Given the nature of his bill, it would appear the conversation he really wants to have is whether politicians should, in fact, have the power to expunge curricula of books they don’t like.

There is no reason why the working class cannot at the same time be the intellectual one. The efforts of the Howard Zinn Project to advance this in the classroom, and the reflexive opposition from adjudicators such as the introduction of this bill, would ask educators and students alike to be optimistic without being complacent.

Read Jas Chana’s full post at truthout