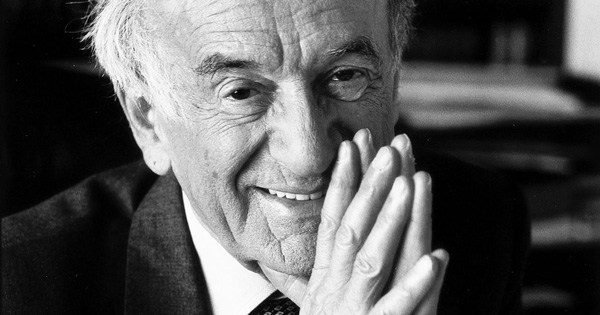

Sultan Doughan earned her PhD in Anthropology from UC Berkeley and currently serves as post-doctoral fellow at the Elie Wiesel Center for Jewish Studies. We spoke with her about her current Anthropology course on the meaning of memorials. The conversation is edited for clarity.

EWCJS: Why do we put up memorials? What's their purpose?

Sultan Doughan: When I say memorial, I refer to public sculptures and monuments as well. A memorial is characterized by its function to prompt us to build a particular relationship with a past event. We put up memorials to make claims about the past in the present, but we also do it for future generations. We memorialize important events or personages we associate with such events. Consider war memorials for example. They remember the fallen soldiers and immortalize them as foundational for the national-political order. The memorial commutes the soldier’s death into a sacrifice and also keeps his or her memory alive to the community. Memorials of this sort are a recent phenomenon, because they combine political events with a notion of history that orients the modern state and its legal institutions toward the future.

EWCJS: Surely there have been memorials from time immemorial.

Sultan Doughan: There were older monuments and sculptures of course, and in a sense temples and houses of worship are memorials, too, but religious sites prompt and organize memories to cultivate a tradition that transcends our secular-historicist understanding of past, present and future. However, modern memorials have a very different function; they organize and trigger very different practices. The purpose I think is most important: remembering the dead and offering a form of grief, or bringing justice by displaying their death publicly as something that served a greater political purpose. Or a memorial can point to death that still needs to be reckoned with such as the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, informally known as the Lynching Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama. The Lynching Memorial commemorates a particular form of murderous crime that Black communities have been experiencing since the abolition of slavery. As a site that thematizes lynching, it still asks for justice by displaying unresolved and ongoing injustice. Those who visit might see a warning from a racist past, but also the possibility to reflect on the ongoing racism and inequality. The memorial lends itself to both of these perspectives, by having names etched into the hanging slabs and short case descriptions on placards. It is a memorial that warns and prompts to reflect on an unfolding history.

EWCJS: You grew up in Germany, a place many associate with its Nazi past, but that is also hailed for the way it has been coming to terms with that past. How would you characterize the difference between German and US memorial cultures?

Sultan Doughan: In the German language there is a crucial difference between ‘warning memorials’ (Mahnmal) and ‘thinking memorials’ (Denkmal). Warning memorials can display a catastrophe and a stain of shame and guilt such as the various memorials that are dedicated to Jewish suffering and death under the Nazi-regime. Some of these memorials include photos of Nazis, but the purpose of the site is clear, and it is obvious that what is on display is not to be celebrated or engaged with in a casual manner.

‘Thinking memorials,’ in contrast, have a wider range of expression and can be dedicated to all kinds of historical events and public personages. The main objective is to make you think, wonder, and reflect. In a way, the German memorial landscape provides you with a normative map, whereas in the US, you can have many different memorials standing equally next to one another without that distinction in naming, but you might see differences in material, form, color and structure.

In the US, a widely-held assumption seems to have been that all these different and mutually exclusive memories can coexist peacefully. But as we have seen over the last few months, with statues beheaded and monuments defaced or disputed for what they represent, it has become clear that these memorials are not necessarily growing out of a historical past, but are often the result of a desire to shape the political present through myths that have sustained a certain social hierarchy. Many of the confederate statues were built not right after the Civil War but during the Jim Crow era that cemented racial segregation. So clearly these were not warning memorials meant to remind citizens of a catastrophic past, but they served to display a reclaimed and renewed past through the towering figures of confederate generals. Memorials that came directly out of the Civil War and honored the Confederacy were usually commissioned by the “United Daughters of the Confederacy” and here is an interesting gender-aspect to it. As widows, mothers, wives, sisters and daughters these women were grieving the loss and defeat of their male kin and remembering them as unjustly broken and killed heroes. As women and relatives no one could possibly deny their felt grievances. Certainly showing grief was more acceptable for women than for men. Building monuments to remember confederate soldiers as honorable heroes meant to keep up a certain spirit, even when that spirit is nominally defeated. In other words, even those memorials were not simply expressions of grief over private loss but the expression of a patriotic spirit with all its nationalist, mythical, and racial imaginaries. Perhaps it is no coincidence that over the years these memorials have acquired celebratory status and are not associated with rites of mourning.

EWCJS: What exactly is at stake here? Is this about contested pasts, about resistance to change, or a struggle for the future? Can there be memorials that overcome, rather than enhance, the racial and political divides?

Sultan Doughan: So, this is a really interesting point. First of all, I think US-Americans (please allow me that generalization, I will specify in a bit) have a curious relationship to history. In a way, I think that Germany, my primary research context, and the US have a lot in common: a fascination with, and an anxiety about, their own past. History, in this sense, means to be able to tell a story, to have a narrative about a place, to come to a certain judgment on an era or a political event. History, as an object of national story-telling, is often reenacted by volunteers, who participate with a sense of pride. But the way history is displayed in monumental ways seems like an anxious gesture to meticulously reproduce artefacts of evidence that Americans are really rooted here as a nation, when in fact the most iconic memorial sites point to the inability to be one nation. Consider for example some of the monuments on the National Mall in DC, such as the Lincoln Memorial, or the Vietnam War Memorial that caused a controversy because it was designed by Maya Lin, an Asian-American female architect. History as a narrative of certain events that can be memorialized then remains fragmented and points to divisions within larger society. These divisions are never fully articulated in monumental display, but what event becomes memorialized and which communities are included in public display is telling in itself. It is no coincidence that Martin Luther King Jr. chose those particular stairs in front of the Lincoln Memorial to deliver his famous “I have a dream” speech. Besides the fact that Lincoln led the Civil War to abolish slavery and promised some form of basic equality, the memorial itself can be understood as a tribute to this incomplete promise. Dr. King literally stepped into the Pantheon of the United States to bear witness to the absence of African-Americans from these sacralized spaces and laid a claim for a different future.

EWCJS: This is very interesting. Can you say more about that?

Sultan Doughan: Absolutely. And here I want to become more specific about my earlier claim about US-Americans. African-Americans are never fully present in these grand histories about the US. I think scholarship on African-American history is an absolutely vibrant field, but it’s knowledge and archive is barely reflected in public memorials and monuments. There are of course initiatives to build memorials to major events and eminent personages in African-American history such as “The Embrace” Boston is planning to honor Marin Luther King Jr’s non-violent legacy, or memorials to slavery such as the one on the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, campus. But one also has to keep in mind that most parts of the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville, were built by Thomas Jefferson’s slaves. Some of those campus sections are a UNESCO world heritage site. They may as well be a memorial site in itself, bearing witness to what African-Americans have contributed to this country by their very labor, while being excluded from benefiting from it. But what do these memorials tell us about the conditions of African-American life right now? What do they tell us about the incomplete achievements of political equality, given that African-Americans remain underrepresented in elite spaces like the university? Given that Black lives are systemically victimized by the manner in which law and order is administered across the country, what do we make of a memorial that tells us that we should be proud of Dr. King’s non-violent legacy? Why do we exceptionalize non-violence when we memorialize African-American history? Is it because, deep inside we know that the violence of 400 years of brutal inequality could have begotten far more violent reactions from African-American communities? My point here is that these clearly designated memorials seem to give shape to a present anxiety of wanting to correct history, when simply all the signs point in a different direction.

EWCJS: If I understand you correctly, there is more to memorials than just the commemoration of a past.

Sultan Doughan: History in itself is more than just a narrative account of past events. Genre and emplotment shape our understanding of a certain history, but also the kinds of concepts we use in telling the story. And I am obviously saying this as someone who engages with history not as a historian, who reads archival documents, but as an anthropologist. My basic unit of analysis is the subject whose actions are embedded in a particular practice and rationale. From this perspective, memorials are a fairly recent phenomenon. Communities and groups have built these types of monuments with the intention of shaping a particular kind of modern subject, one that thinks within the horizon of the nation-state.

On the one hand, the desired subject of these memorials is aligned with a particular public narrative, a politics of memory, if you will. By virtue of that narrative, communities re-organize and synchronize themselves within the time of the nation-state. This may include claims to transitional and racial justice. On the other hand, as objects embedded in a practice and a particular narrative, memorials change because the commemorating subjects change due to generational shifts, due to the emergence of different sentiments, due to shifts in political orientation. In other words, changes in the political present make it possible to forge a different attitude toward a memorialized past event, such that it can no longer be reconciled with the promise of national belonging, citizenship, or justice. Memorials can turn into empty symbols or remainders of broken politics. At the peril of making a presentist argument, I would say that memorials also have the function to sustain a political order in the present. When that political order crumbles, memorials lose power as well. The desire to break them is interesting in itself, because most often something is left when a statue is removed, an empty pedestal or pieces of the monument point to the absence of something that used to be there. Perhaps not visible anymore, removed out of sight, but those who know the history can see behind the absence another layer of a present past. Ruins are examples of indexing absence through presence. The full meaning and effect of such a ruin is a fascinating subject of research. I am mostly thinking of confederate and colonial statues in the US, Germany, and the UK. For many people who have been active protesting on behalf of Black lives, confederate statues are a materialized piece of segregationist terror that Americans of color have lived with. In the UK, the story is about addressing post-colonial inequalities, decolonization in its materially inflected sense. In Germany, a consequential debate about Germany’s colonial past has not really started yet. But in all of these cases, a more thorough discussion about racial inequalities is needed. These sedimentations of historical events have shaped us as communities, societies, and nations. They shape the way we approach these built artefacts with our senses and sensibilities. These sedimentations are only epitomized in the memorial, but never just residing there. History education and public commemoration inculcate a form of experience that is expected by institutions of power.

EWCJS: Who is responsible for creating memorials? In Boston, the Jewish community raised money and helped build a highly visible and public Holocaust memorial. The Irish famine memorial was funded by a trust supported by private donors representing Boston's Irish-American community. Doesn’t this suggest that many memorials we see here are simply a reflection of the multi-ethnic makeup of American society?

Sultan Doughan: Ideally, the community affected has a say in the memorial, as in the examples you have mentioned. But there is something fascinating about your examples, because they reflect a passage from the old world and its burdens to America as the newly found safe haven. To memorialize the Irish famine and the Holocaust here and now associates geographical relocation with the judgement that things have been better since the arrival in the New World. In a way, this dovetails well with the story of the US about itself as a liberated post-colony. Europe is a space of terror, injustice, scarcity and poverty, while America provides space for betterment and communal revival. There is certainly an old world/new world divide here, but also a promise of those who left not to forget and from this pledge to cultivate their own communal identity.

In my survey of memorials in the US, I have noticed that memorials of tragedy are usually attributed to the outside. This outside is either territorially external, as in the Vietnam War Memorial, or it is a spirit of evil that should be banished and removed. Monuments that commemorate slavery and violence against African-Americans in this country reverses this logic in that it casts the US as a territory of captivity and tragedy. It therefore counters the narrative of freedom and democracy that the US has produced about itself and exported to the rest of the world.

EWCJS: What's the history of changing and removing memorials? How does a memorial change once it is placed in a museum or a collection designed to remind us of a bygone part of history, good or bad?

Sultan Doughan: I think a memorial can only change when it does not produce the same sensibilities anymore, and rather becomes a disturbance or a stain. I do not know the history of removing memorials, but I know that for example the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue was a big media event. The image circulated widely and was taken as evidence that Iraqis have finally liberated themselves from their dictator. Documentary footage, however, showed later that a group of men were brought in a bus from outside of Baghdad to do this act, and they were also aided by an American tank. In other words the toppling was staged. Of course, we don’t really know the motives of the participants, but it seems that the act of visible destruction was powerful enough to stand as a claim in itself. Famous cases of toppling memorials occurred in Russia following the collapse of the Soviet Union, where gigantic statues of communist leaders such as Lenin and Stalin were torn down. It turns out that the Russian government actually saved many of these sculptures by dumping them in the sea. From memorial to museum is an interesting question, one that has been on my mind recently, when the Hagia Sophia was turned into a mosque, once again. The building was originally a Byzantine Roman imperial church that, after the Fall of Constantinople became a mosque and that the Kemalist Republic of Turkey turned into a museum. To turn it back into a mosque, as was just done, demonstrates the decline of the Christian community, and – as a mosque in a country full of mosques – it is a site of Sunni-Muslim supremacy and an expression of religious-nationalist politics. I am not sure if it’s worse than having it kept as a museum; this would be an empirical question for the affected communities. It remains to be seen who will use this converted site for regular prayer. In this case, we went from claiming the site of another community as something that, while passé, is a cultural heritage worthy of preservation to claiming that same site for the purposes of majoritarian politics. This form of converting the meaning and function of a heritage site is not unique to Turkish politics. For example, a former Palestinian mosque in Safad was recently turned into a fancy Israeli restaurant. It seems that the mosque was partly destroyed and not in use anymore, but what became of it was decided by agencies and rationales from outside of the community that was originally attached to the site.

EWCJS: So what do you do in your course?

Sultan Doughan: My course on memorials deals less with these actions of repurposing. Instead I bring together notions of racial and transitional justice, after violent events, with the emergence of a built site. I want to understand how memorials become sites of evidence and claim-making as well as the kinds of practices they trigger and invite. For communities that have been the victims of violence, memorial sites become a place to unload and organize sentiments of grief, despair, hope, or even just a site to cultivate these sentiments. At the same time, memorials can also be completely co-opted by a nationalist politics or politics of denial or refusal, for example, when they are built by the community of the perpetrators who now want to help repair and reconcile. I am thinking for example of the war memorial built in Germany during the 1990s that commemorated all victims of war of all wars. This gesture also included Jewish victims, but the statue was a version of the Pieta leaning over her son, turning a specifically Christian image of a mother crying over her killed child into a universal gesture. But the Pieta, a well-known image, still represents the Virgin Mary. It is circulated as a Christian image of compassion. So how are we to understand this gesture in a memorial site that is supposedly also inclusive of Jewish victims? And should all victims be grouped together when there is a glaring inequality in the distribution of compensations? Does grouping them together enable a better or fairer distribution of justice? Again, I am obviously speaking here from the research case of Germany that has generated these partly unresolved questions. In the US-context we might see more of that in the future, as the demand for reparations gains more traction. This demand will have implications for other groups as well, such as the indigenous First Nations. So, in this sense I am interested in memorials as these ambivalent artifacts that have an effect on us and shape how we mourn, seek justice, remember, and imagine past and future in a nation-state founded on originary violence. In the course, I explore different historical cases and complicate notions and concepts that grow out of human rights discourse. I ask how these concepts, which emanate from those in power, develop a life of their own as they are perceived by social collectives. These concepts become organizing devices for certain groups to orient themselves in new experiences of violence.

EWCJS: Many thanks for speaking with us and good luck with your course!