By: Michael Zank

Passover is the first Jewish holiday I remember. My mother, a German Jew who had survived the war in England and returned to Germany in 1950, took me to a community Seder in the Jewish old-age home in Neustadt/Weinstraße, near our hometown of Bad Dürkheim. The event included sitting at one of the many tables that had been arranged in a large rectangle inside a non-descript hall and listening to a darkly clad rabbi read aloud from a book. We sat right across from the rabbi. The first Hebrew word I caught after a while and remember forever was the most often repeated one: mitzrayim. It also occurred in the variation of mimitzrayim. Mimitzrayim, as I eventually learned, means “out of Egypt.” After the meal, a youth group sang some songs, accompanied by bongo drums.

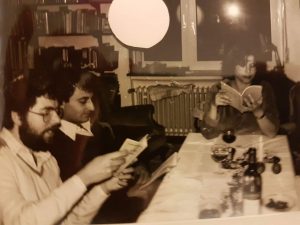

I am glad that Passover was my first encounter with the Jewish tradition. I have loved it since. When I was a student in Jerusalem, my friend Gavriela, a German convert to Reform Judaism, gathered a motley crew of friends around her living room table for the first Seder I helped conduct. I had studied up by then. I had attended a mock Seder, held in the bowels of the Ratisbonne monastery on Rehov Shmuel Ha-Nagid by the charming Shalom ben Chorin, then a major Jewish German voice in Christian Jewish dialogue, and I had studied the Goldschmidt Haggadah, with its historical commentary. I accrued a collection of facsimile Haggadot with wild ornamentation that indicate what children really did year after year during interminable stretches of reading before dinner. The beauty, care, joy, worry about getting things right, the tastes, the cacophony of voices, the rhythm of the evening, the repetition year after year, all this imprinted Pessach into my DNA as a belated Jew.

Pessach is now a tradition in my family, though not a simple or straightforward one. We always have Christian friends at our table and the question is always, what is this holiday about? The quick answer is: we celebrate our liberation from slavery in the Exodus from Egypt. The longer answer is that Passover, which coincides with Hag ha-Matzot, the Feast of Unleavened Bread, combines two distinct seasonal traditions, one rooted in the religion of semi-nomadic herdsmen who celebrated the firstlings of their flock, the other rooted in sedentary populations of Canaan, marking the beginning of the barley harvest and the counting of the “Omer,” a fifty-day period, until the beginning of the wheat harvest. Both the firstlings of the flock and the first harvest of the year reflect the fragility of the lives of herdsmen and subsistence farmers in the ancient southern Levant where everything depended on rain falling at the appropriate times. Anyone who has had the chance of seeing the wonders of the Judean desert blooming in early spring understands this dependence of life on the clouds opening their gates at the right time.

What is more difficult to explain to our Christian friends are some of the passages in the traditional Haggadah that reflect centuries of Jewish pain and persecution. The call for God to “pour out his wrath” over our enemies, the ritual of opening our doors in answer to the medieval Christian suspicion that the Jews conducted nefarious rituals in their homes, the sadness of exile embedded in the hopeful call at the end of the Seder to celebrate the next Passover in Jerusalem. No matter the degree to which we have changed and amended the Haggadah to be more inclusive and more universal, Passover ritually reminds us of our foreignness and alienation. It celebrates our origins as a nation singled out by divine salvation. And yet, the Haggadah accomplishes the seemingly impossible. Tonight, we welcome strangers, we invite those who are hungry to come and eat, we imagine the passage from slavery to freedom together with our guests, looking toward a better, more just and less hateful future.

Our friend Susannah Heschel placed an orange on the Seder plate to symbolize inclusion of difference. Originally, the orange symbolized the need to accept every Jew, regardless of sexual orientation. If we associate the fruit with the success story of the “Jaffa Orange,” then perhaps it can also remind us that the orange belongs to all people of Israel and Palestine, Jews and Muslims, Druze and Christians alike; that our freedom remains incomplete until everyone is free to enjoy the fruit of their labor and the produce of the land; until everyone can rest in the shade of their olive tree. May we celebrate Passover Next Year in a Jerusalem rebuilt as a shared city for Israelis and Palestinians alike.

Wow what a lovely blog information is very useful