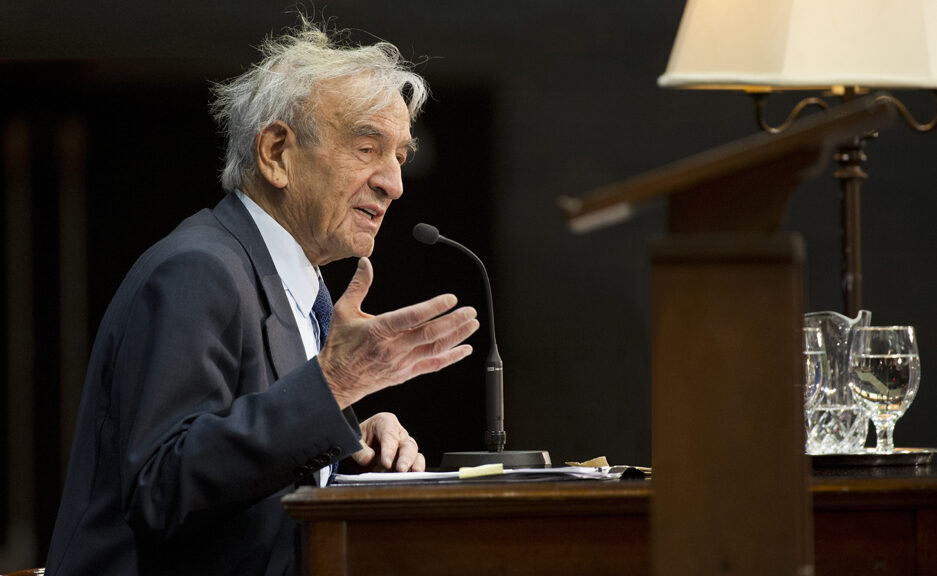

by Ingrid Anderson, PhD,

Associate Director of the Elie Wiesel Center for Jewish Studies

Ingrid Anderson earned Masters and Doctoral Degrees in Religion, with a specialization in Jewish Studies, at Boston University, where she has been teaching in the Kilachand Honors College, the CAS Writing Program, and the Jewish Studies program of the College of Arts and Sciences. This year, she has spearheaded teaching a new course, titled World Cultures of the Jews, which is a required course for the Minor in Jewish Studies. Her first book Ethics and Suffering since the Holocaust (2016) is a study of ethics as “first philosophy” in the works of Elie Wiesel, Emmanuel Levinas, and Richard Rubenstein.

The topic of Jews and race is complicated. But exploring race is more important now than ever. The Black Lives Matter movement has prompted many white Americans to become more aware of “white fragility” and white privilege. Meanwhile, anti-Semitic incidents in the U.S., as tracked by the Anti-Defamation League since 1979, reached an all-time high in 2019.

Officially, Jews have long been considered “free white persons” in the U.S. They were permitted to become naturalized citizens under a 1790-law passed by the first Congress. Yet in 1911, Jews were re-classified as “not quite white” by the Dillingham Commission Report, which identified 36 different European “races,” and some Jews were classified as “Hebrew.” The report was largely a reaction to the millions of Ashkenazi Jews from Central and Eastern Europe who flocked to America since the early 1880s. The first wave of refugees fled a Czarist Russia that fomented anti-Jewish violence. Other violent incidents followed in 1903 and 1905 (Kishinev pogroms). Ashkenazi Jews brought with them dreams of equality, and many were instrumental in creating the labor movement. America was, in Yiddish, di goldene medine.

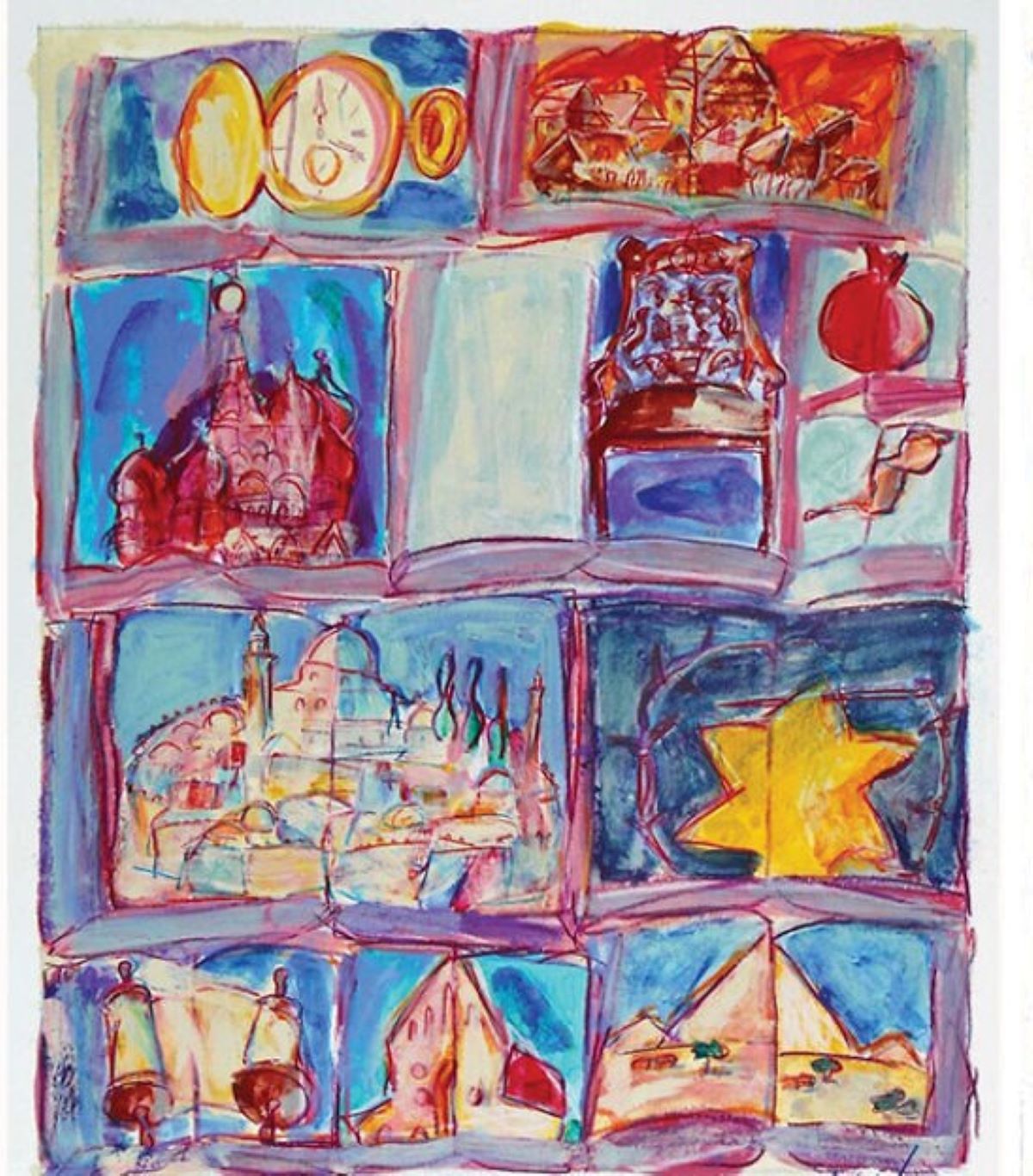

The influx of Ashkenazi Jews, who today make up about 80% of American Jewry, profoundly changed the demography of the American Jewish population. The first Jews to settle in the Americas had been Sephardi Jews from Southern Europe and North Africa. The two oldest synagogues in the U.S., Touro Synagogue, Newport, RI and Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim Synagogue, Charleston, SC are Sephardi, and they are still in use today.

In 1924, the passage of the Johnson-Reed Act (also known as the 1924 Immigration Act) established a quota system that limited primarily Jewish and Slavic immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe and barred Asian populations completely. This racialization of Jewishness set the tone for the interwar period as the most anti-Semitic period in American history. In the decades following the end of World War II, life began to improve for many American Jews, especially for those who had served in the war and were eligible to receive GI Bill benefits that emphasized education. The GI Bill helped foster a long term expansion in white wealth, including white Jewish wealth. Black Americans benefited far less from it than whites, especially in the South. The GI Bill did not, in fact, lead to a significant growth in Black wealth. The law benefited many American Jews, especially those who “presented” as white, even though religious stereotypes and prejudice against the Jews prevailed, leaving them with a sense of distrust toward non-Jewish America’s “embrace” of Jews.

However, not all Jews are white people, even if most Americans say they are. 12-15% of American Jews are people of color, and many young Jews who grew up in multiracial households identify as non-white. This means that 1 million of America’s 7.2 million Jews are non-white, and Jews of Color account for approximately the same percentage of the American Jewish population as Black Americans represent in the general population. Counting Inconsistencies, a new study by the Stanford Graduate School of Education, found considerable inconsistencies in how Jews of Color were counted in recent population studies of American Jews, because many studies didn’t even ask about race or ethnicity. This is likely because they assume that Jewishness is a race or ethnicity that any Jew would name as their primary identification. That many researchers who focus on Jews and Jewishness think of Jews as white and of Eastern European extraction—with a few “statistically insignificant” exceptions that “prove the rule”—means that American Jewry is largely ignorant of its own diverse nature and subsequently denies the powerful presence of racism in their own institutions.

Founder and Executive Director of Jews in All Hues, Jared Jackson, reports that on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish liturgical year, he gets calls from Jews of Color who are refused entrance to their synagogues. Their Jewishness is denied because of the color of their skin. Many Jews report that their experiences of micro-aggression and racism (subtle as well as overt) keep them from participating in Jewish communal life as much as they would like. Jews are not, in fact, “a race.” The Jewish community is much more diverse than many may suspect: Jewish communal life is a global affair; hence our required course on “World Cultures of the Jews” (JS100).

Jews of Color experience racism from their fellow Jews and anti-Semitism from non-Jews on a regular basis. Jews of Color are often demeaned in conversations with their fellow Jews in ways that white Jews are likely not even aware of. The most basic example of this are questions like “So, HOW are you Jewish?” or “When DID your family convert?” Jews of Color are even accused of lying when they tell fellow Jews that they are Jewish. Despite their physical presence in Jewish spaces, they are often made to feel invisible.

What can white American Jews do, who want to join the fight against racism and support anti-racist organizations and policies? Start in our own backyards! Many white people who want to support the Black Lives Matter movement turn to People of Color to tell them how. This is a mistake. If you want to join the fight against racism, teach yourself about the history of racism and white privilege. There are many resources available. Find out exactly how white privilege works, and if you are a white Jew, you need to understand that, in the U.S., white Jews have white privilege. Interrogate your understanding of Jewishness. Bravely consider how you, as a white Jew, despite the scourge of American anti-Semitism, may succeed more easily than Americans of Color because of your whiteness and in spite of your Jewishness. Learn more about American Judaism by studying the work of Jews of Color and support their efforts. Learn from the work of Jews of Color. Here are some suggestions on where to start:

There are many books, websites, newsletters, and films to choose from. Consider Rabbi Sandra Lawson, the first openly gay, female Black rabbi in the world. Read the amazing words of Shais Rishon, known as MaNishtana. His books include Thoughts From a Unicorn: 100% Black, 100%. 0% Safe, and The Rishoni Illuminated Legacy Hagadah; if you prefer fiction, look at Ariel Samson, Free Lance Rabbi, Rishon’s remarkable first novel. This is the story of a “black Jewish Orthodox rabbi looking for love, figuring out his life, and floating between at least two worlds.”

If you want to become involved in active Jewish anti-racism, consider Bend the Arc, a progressive Jewish action organization that has joined the Black Lives Matter movement. Or visit Jews in all Hues on Facebook to find out how this organization facilitates conversations about race. Subscribe to Alma and JTA, which regularly feature pieces written by Jews of Color.

How about Yitz “Y Love” Jordan? Yitz Jordan is a Black Jewish gay man who is a musician and JOC (Jews of color) activist. Jordan founded The Tribe Herald, a JOC news outlet, and is currently raising money for a JCC for Jews of Color. Shais Rishon and Y Love are also featured in Punk Jews.

Explore the work of Yavillah McCoy, who founded Ayecha, a non-profit Jewish organization that provides Jewish diversity education and advocacy for Jews of Color in the U.S. She is currently CEO of Dimensions, an organization that provides training and consultancy in diversity, equity, and inclusion. Or check out the play she co-wrote, The Colors of Water. Follow Amadi Lovelace, whose Twitter feed is an excellent source for information during BLM protests. Go to Tema Smith’s website, a collection of valuable resources about community building, Jews, race, diversity, and interfaith families.

Want to learn about initiatives for “building and advancing the professional, organizational, and communal field for Jews of color”? Visit the Jews of Color Initiative website. Attend a live online Be’chol Lashon event that celebrates Jewish diversity.

American Jewish communities are not alone in struggling with intra-Jewish racism. As painful as it is for some to acknowledge, Israeli society also suffers from long-standing prejudice against Jews of Color, let alone Jews of Arab origin. Israel is the home of diverse communities of Jews. Nearly 15% of the Jewish population is of African descent, 11% are of Asian descent, 38% are of Arab and other Middle Eastern extractions, and only 36% are of European descent. For many of my students, the diversity reflected in Israeli society offers a first glimpse of the surprising racial and ethnic heterogeneity of Jews and Jewishness. But this diversity is not always gladly embraced. Read the heartbroken words that model, singer, and radio host Tahuonia Rubel penned when Ethiopian Jews took to the streets during the summer of 2019 to protest the murders of Ethiopian Jews by Israeli police. Here is an excerpt from a June Instagram post from Rubel’s feed responding to Israeli celebrity posts stating that Black Lives Matter:

So much grief is caused here [in Israel] to ‘Blacks’ as you say in your do-gooder posts that I don’t remember that one of you uploaded a black picture when we blocked the roads [in summer 2019]! When you called us hooligans! When we broke glass! When we burned tires! When we cried tearfully the name of Yosef Salamsa! Solomon Tekah! Yehuda Biadga! And so many mothers who are crying every day for their children!! Get out of the horrifying bubble you live in! … You are far from empathizing with our pain!

Given that 40% of all Ethiopian Jewish men serving in the Israeli Defense Force have “seen the inside of a military prison,” Israel, too, must commit itself to identifying racist policies, abolishing them, and in turn adopt anti-racist policies.

Last but not least, white American Jews, when American Jews of Color like Shais Rishon say that “at least there is Israel” offers no comfort to them in times of American political turmoil, listen. They are telling you that the idea that Israel is a shelter from the disease of bigotry for all Jews is still, for now, just a dream.

If you had told me two months ago that I would be finishing college from my bedroom on Zoom, I would probably have laughed. A global pandemic? Postponing commencement? Nice try.

If you had told me two months ago that I would be finishing college from my bedroom on Zoom, I would probably have laughed. A global pandemic? Postponing commencement? Nice try. Look no further than actor John Krasinski’s new YouTube show,

Look no further than actor John Krasinski’s new YouTube show,