Guest blog-post by Katya Tsvirko (CAS ’21), an International Relations major and currently a student in CASRN101/JS120 The Bible with Professor Zank.

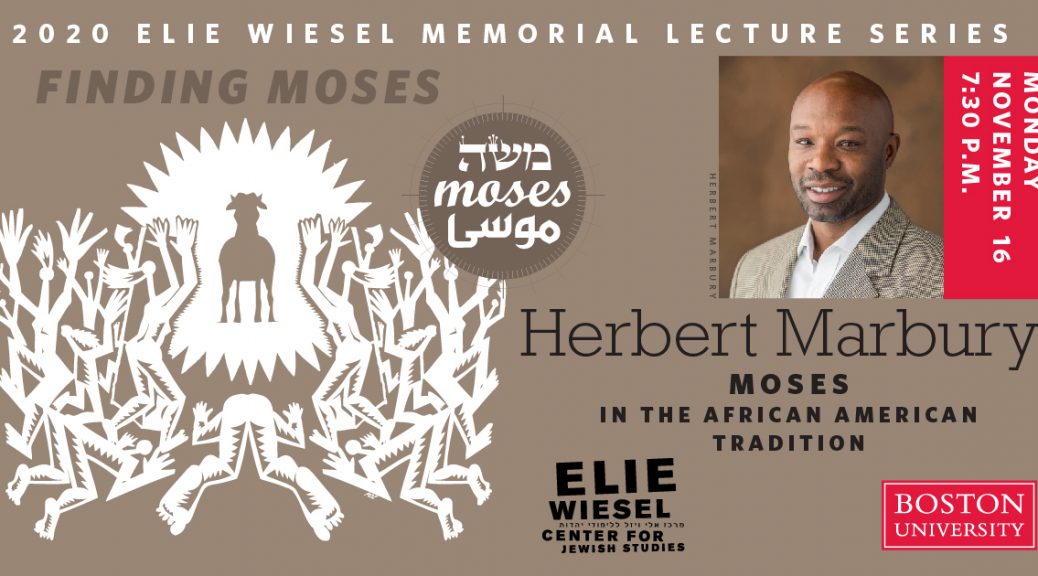

Dr. Marbury’s lecture left me reflecting on the power of biblical interpretation; his presentation answered one of the biggest questions I had since I first started reading the Bible this September: how do these chapters and verses impact their readers? In answering this question, Dr. Marbury looked at the cyclical interpretations of the Bible and biblical figures through the lens of racism, feminism, patriarchy, and oppression.

One part of the presentation that strikes me is the story of Gronniosaw, an enslaved man on the boat who encountered the Bible for the first time. Through Dr. Marbury’s summary, I understand the story this way. Gronniosaw sees his white captain reading a book (the Bible) aloud and decides to attempt to hear the book on his own; however, when he puts his ear on the book, it doesn’t speak. His conclusion is that the book, like everything else in his world, hates him because he is Black. To give context to Gronniosaw’s actions and deep hurt, Dr. Marbury explains that in traditional African religions, spiritual objects such as talismans often speak to people and believers. It is for this reason that the main character in this story feels so defeated and rejected that the book which spoke to the white man chose not to speak to him. What was particularly striking in Dr. Marbury’s retelling of this story is his analysis that, naturally, the book was silent to both men, but their separate politics is what fills that silence— “the vanquished versus the conqueror.”

In extending this story to the larger history of African Americans in the United States, Dr. Marbury introduced a conceptual framework for looking at the African American interpretation of the Bible: mythic cycles. He proposed the idea that during slavery, the promised land meant emancipation; from the mid 19th to the early 20th century, the promised land meant self-development, and during the Civil Rights era, the promised land meant equal civil standing. This idea of a mythic cycle also extended to the time of the Harlem Renaissance, in which the promised land now equaled the product of self-improvement, rather than self-improvement by itself. Dr. Marbury gave an extensive outline of the African American experience in WWI, from the creation of a new urban Black working class, to the recruitment and authoritative experience of Black men serving in the U.S. army during their deployment in Europe, and then the desire for authentic Black representation in art; this was the context to Zora Neale Hurston’s book Moses, Man on the Mountain.

Dr. Marbury’s clear analysis of the book was compelling, and I hope to read the book myself sometime soon. I was fascinated by the feminist lens he adopted in his analysis of Moses’s sister Miriam. His argument that her imagination is what forms the glory and legend of Moses was incredibly thought-provoking. Perhaps it even ties into recent discussion during a RN101 lecture in which it was pointed out that much of the backbone of religion is human fantasy; although it is powerful and incredibly significant for its followers, the fantasy is what drives the religion. Thus, Dr. Marbury posits that it is a woman’s fantasy/imagination that establishes, for an entire community, this idea of Moses and his glory. The woman, Miriam, is able to enjoy community leadership and authority, until Moses returns and can’t accept female leadership. Then, she is made powerless against him and even feels that he controls the power of life and death. In essence, this relationship compels the readers of Hurston’s book to consider the odd fact that Moses, a figure whose glory is owed to Miriam, ends up overpowering her.

With this message, Dr. Marbury concluded his lecture, saying that Hurston’s biblical interpretation attempted to give the power of religion back to the people; it was people that could lead themselves to transcendence, they didn’t necessarily need to wait around for an individual, a messiah, to lead them.

All in all, Dr. Marbury’s presentation was thought-provoking, compelling, and clarifying for a student who began reading the Bible only three months ago. Entering a sphere as complex as religion is a difficult and rewarding task, but understanding how people interpret religious texts makes it easier to read the Bible as literature. The authors of the Bible were driven by their political and social issues, and readers are also susceptible to interpret it according to their socio-political needs. I wonder what religious texts would look like if they hadn’t been written with an angle? Would people still have felt drawn to them? As Dr. Marbury quoted, “‘Gods always love the people that create them,’” and with this in mind, I hope to continue neutrally analyzing religious literature while exploring its social and political interpretations.

If you missed Dr. Marbury’s lecture, you can watch it on our YouTube channel at https://youtu.be/m4JQghlWGX4.