By: Katherine Gianni

Grey skies and passing showers did nothing to deter those recognizing Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, on Thursday morning in Marsh Plaza.

Hosted by the Elie Wiesel Center for Jewish Studies and Boston University Hillel, students and community members alike were invited to light a candle, say a prayer, or remember a loved one who may have perished in the Holocaust. A ceremonial Reading of the Names began as Marsh Chapel’s bell tower chimed 9:00 a.m.

Miriam Angrist, a senior lecturer in Hebrew and Head of the Hebrew Language Program was one of the first people up at the podium.

“I’m reading the names of those who’ve perished to show that I will not allow them to be forgotten,” she said, her words echoing across the expanse of the plaza. One by one she recited the names from a booklet as thick as a dictionary. Hillel student president Connor Dedrick said that each participant will read for 10 minutes, getting through approximately 100 to 150 names.

“At the end of the day we leave a bookmark where the last reader finished up,” he explained. “In one year it’s impossible to get through all the names we have in this book. It normally takes six to seven years to read every single name.”

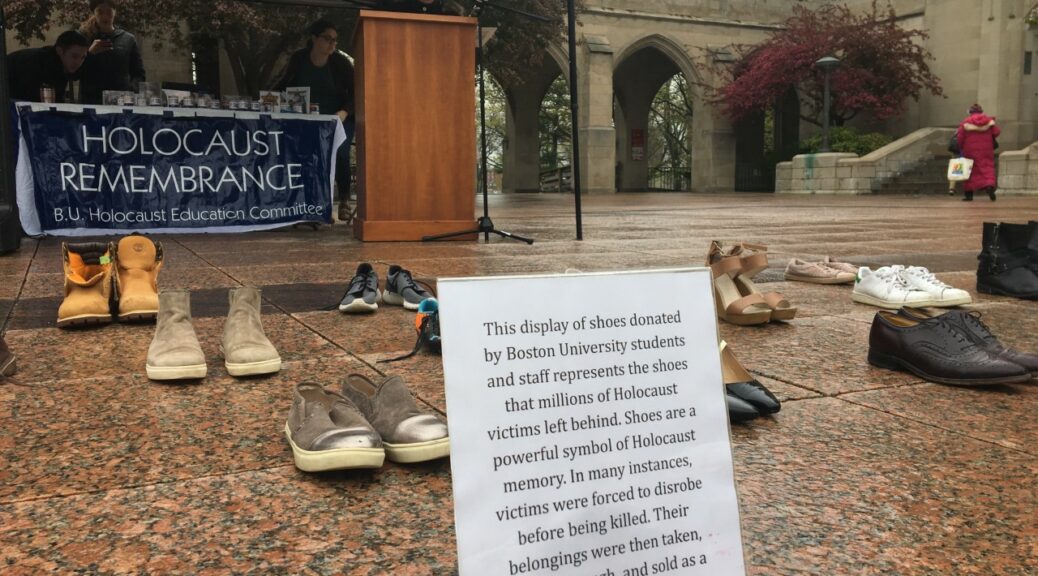

Rows of shoes were displayed in front of the podium to symbolize the millions of Holocaust victims. Hillel Holocaust Education Chair Tallulah Bark-Huss explained that shoes are often used in Holocaust museums and memorials around the world to commemorate those who lost their lives.

“The shoes themselves were donated by various BU students,” she said. “In many instances, Jews were told to take off their shoes before being killed. A famous memorial is in Budapest called the Shoes on the Danube Bank, so I was inspired, in part, by that. I felt like we should utilize all of the space we have here at Marsh Plaza.”

As the observance continued, one student approached the array of sandals, boots, and sneakers to add a pair of his own.

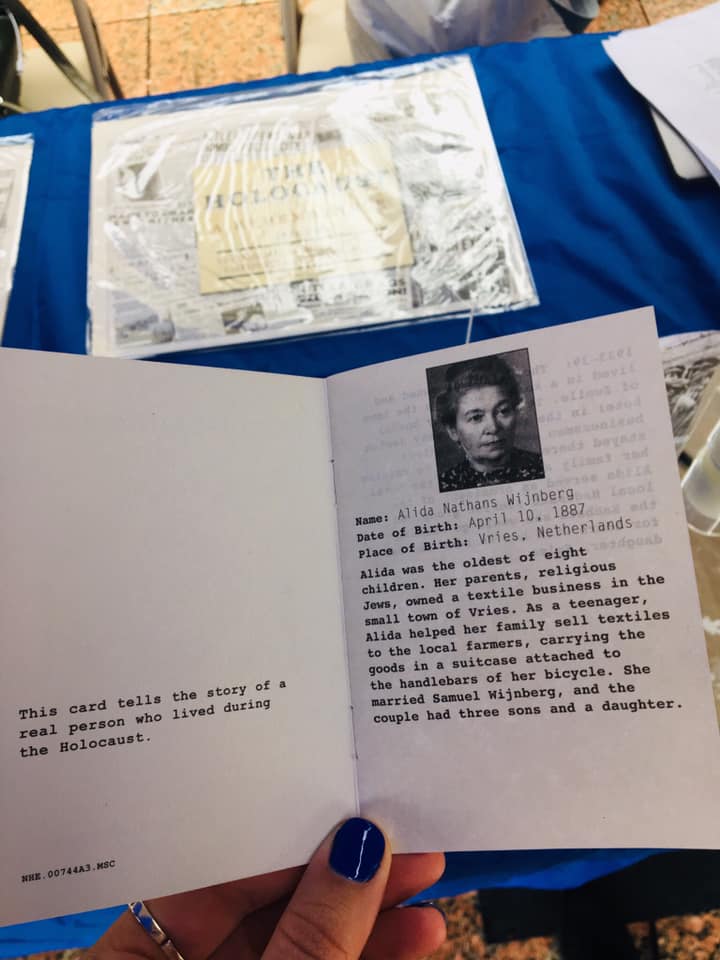

Two tables sat behind the podium, both showcasing an array of photographs, candles, and even identification cards from the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. Each card tells the story of a real person who lived through the Holocaust. BU senior Carmelle Dagmi, who organized the event two years ago, offered the cards to passersby.

“I really hope that when people come by today that they participate and help to keep the memory alive,” she said. “I feel like I have a personal responsibility to hear the names and remember the stories.”

Mr. Dedrick read his share of names following Professor Angrist. She stood alongside the display in quiet reflection.

“This means the world to me because not only do I recognize Remembrance today, I live it on a daily basis,” she said. “We are a community that gets together on special occasions, both sad and happy. I hope that people really just take a moment to reflect.”

At 5:00 p.m., event organizers, students, faculty and staff will convene for a short ceremony which will include speakers, poetry, and candle a lighting. All are welcome to join. For more information visit https://www.bu.edu/hillel/calendar/.