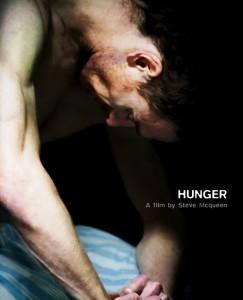

There is a man lurched forward. His shirt is off, but his striped blue and white pants radiate in the background. The man’s face is emaciated but his expression is without pain or happiness. Where his skin isn’t stained red from blood or bruising, it is a bland pale white. This image is featured on the cover of one of Criterion’s latest release, the 2008 film Hunger. The man is Irish Republican Army member Bobby Sands (Michael Fassbender) during his (in)famous hunger strike in 1981 as shown in Steve “not that one” McQueen’s debut masterpiece.

There is a man lurched forward. His shirt is off, but his striped blue and white pants radiate in the background. The man’s face is emaciated but his expression is without pain or happiness. Where his skin isn’t stained red from blood or bruising, it is a bland pale white. This image is featured on the cover of one of Criterion’s latest release, the 2008 film Hunger. The man is Irish Republican Army member Bobby Sands (Michael Fassbender) during his (in)famous hunger strike in 1981 as shown in Steve “not that one” McQueen’s debut masterpiece.

Sands’ hunger strike was part of a movement in the early 1980s by the IRA to have its prisoners recognized as political prisoners, rather than common criminals. As prisoners of war, they would be able to wear their own clothes, and demonstrate politically. The British government steadfastly continued its tradition of thinking that he I.R.A. as nothing more than street thugs. McQueen sets this situation up right from the film’s beginning in which a speech from Margaret Thatcher echoes on the radio “There is no such thing as political murder, political bombing or political violence. There is only criminal murder, criminal bombing and criminal violence…There will be no political status.” The radio is owned by prison officer, Ray Lohan (in a quiet but incredible performance from Stuart Graham). Lohan begins his daily routine: showering, munching on eggs and ham, checking his car for bombs, and driving to work (the prison) where he beats Irish prisoners. This set up is really the only glimpse of the outside world that Hunger gives; most of the film takes place in the trappings of the Maze prison.

The first act follows Lohan, the next act traces two prisoners surviving in the prison. This beginning half of the movie is notable for a variety of reasons, perhaps the most obvious being its utter lack of almost any dialogue. It is also not really until the film’s halfway point that the audience is even introduced to Bobby Sands. The majority of the film’s dialogue then takes place in a 22 minute scene, between Sands and a priest (Liam Cunningham) that is almost entirely one take. But, none of these plot details really matter, because Hunger is not driven by plot.

Hunger is not like other films, such as In the Name of the Father, that have been made about the IRA. The film is uncompromising in its depiction of the British and the Irish, and also in its faith that the audience will participate in the film rather than simply sit back. This is not the tale of one man’s heroic charge against an evil government, nor is it a prison film in the traditional sense. There is no blossoming male camaraderie. There is no triumphant music. There is no great grandstanding. There are simply people who are put into incredibly difficult, inhumane situations. Director Steve McQueen’s claim in an interview that the audience is “dragged through the process of someone starving himself” is only partly true. Hunger is not simply about a hunger strike, but instead the shades of complexity that exist in prison. As much as the film is sympathetic to Bobby Sands and the IRA, McQueen and co-writer Edna Walsh do not reduce the IRA’s political struggle to a Manichean struggle.

What Hunger is, however, is a fascinating, lyrical and haunting film about the events of 1981. The film is filled with incredible images: the prison walls covered in excrement, prisoners pouring urine into the hallway, Bobby Sands emaciated, almost to the point of death, body. They are never beautiful but always indelible. Even further each shot is meaningful. Precisely because McQueen never idolizes his prisoners, the audience gets a much more interesting view of a day in prison. Just as arresting of an image as those mentioned are the images of the prison guards. McQueen gives the audience a quick glimpse into the life of a young, new prison guard whose only way of dealing with the sheer brutality of the prison is to cry behind a wall as his fellow guards beat the prisoners on the opposite side. McQueen focuses in close up on the man as he slowly falls apart from the new world that he has entered. And yet, it is just as much a part of the prison situation as anything else in the film. When one of the movie’s most brutal acts of violence occurs (the assassination of a prison guard while he is visiting his mother) the film does not linger. It is just part of the story.

Other than Fassbender’s emotional, physical and all-around incredible performance one of the aspects of the film that has received great attention from critics has been the 22 minute conversation between Sands and a priest. Rarely has a static shot been so captivating. While both men are cloaked in darkness and speaking in heavy Irish accents, the obscurity of the situation only adds to the dramatic tension. What begins as meandering babble about cigarettes and life soon becomes a war between the priest, who sympathizes with the IRA but believes that Sands’ hunger strike is a suicidal crusade to get his name in history books, and Sands who is steadfast in his conviction. As Sands blows on his cigarette the air gets smokier and smokier just as the understanding of what is morally correct becomes hazier and hazier. After all the discussion, the only thing left for Sands is action.

If McQueen has one obsession, it is the face. Sands’ face is constantly returned to in the close up, tracing his deterioration and eventual death. Although the doctor who watches over Sands is only shown a few times, his face, a combination of anger, frustration, and sheer sadness, tells a life story. Prison guards’ faces are shown, some seem confused, and others show a certain ecstasy from the violence. Each face is richly textured and it is in the face that each actor delivers an incredibly complicated, complex and deep performance.

Hunger won the prestigious Camera d’or award (for first feature film) at Cannes, and its win was rightly deserved. Rarely has a director seemed so confident and assured in a debut. If Hunger were a more flippant film, I would be tempted to make a silly Pete Hammond-esque pun ending this review (“I have hunger for Steve McQueen’s next film” or “I am hungry to see what McQueen has to offer”). But that would devalue the work McQueen and his actors have done here. Hunger is by no means an easy watch, but its ability to refuse clichéd narrative tricks and hagiographical depictions result it in being one of Britain’s greatest cinematic accomplishments from the last few years.

Special Features:

The film looks stunning. One claim that has been levied against McQueen is that he frames the prison too beautifully, and that the story deserves a grimier treatment. While Hunger is gorgeous it never shies away from the grotesque or the ugly. Criterion has done a great job in the transfer. With a film this dark it’s important to have “deep blacks” and Criterion follows through. While no audio commentary was included in the extras, there is an interview with director Steve McQueen that sheds some light on his approach. He goes into depth talking about how he became interested in Bobby Sands and he also talks at length about the conversation between Sands and the priest in the film. McQueen is clearly passionate and his passion shows throughout the fascinating interview (he makes the polemical claim that the hunger strikes were “the most important event in modern times” for the British). There is also a respectful interview with Fassbender where he goes into what the performance took and how amazing of an experience it was working with McQueen. The way Fassbender’s mental approach to the film seems to coincide with his physical approach to losing the weight is interesting as well. Also included on the disc is a short “Making of” featurette. The piece becomes a bit self congratulatory, and even redundant as much of the information is covered in the two interviews, however any addition is a welcome addition. A trailer for Hunger is also included but perhaps the most interesting supplement is a British investigative news show titled “The Provos’ Last Card?” from 1981. It runs about 45 minutes and illuminates the cultural sentiment towards the IRA at the time. What is perhaps most fascinating is just how much the piece echoes American news shows during the Civil Rights Era. The British narrator uses loaded phrases and repeatedly undermines the IRA movement, describing their actions as a “continuing campaign of murder.” Much of the prison is filmed in this piece and it interesting to re-watch the landscape from the film covered in documentary form here. The great transfer and solid supplements make this a great package overall.

-Nicholas Forster