Photography and cinema, Siegfried Kracauer observed, have a special power to portray happenstance. Often films, trying to use this power, spoil the effect with a certain portentousness: see Crash or the execrable 13 Conversations About One Thing. People encounter one another haphazardly, but random luck sends them in directions already meticulously charted: Initial conflict! Reluctant interpersonal perestroika! Self-discovery! Highly engineered “chance” and transparent moral messages tend to combine rather fretfully. The big problem is that “random encounters can affect people” is not a compelling insight, and seems only present as an excuse for Hollywood’s over-rationalized psychology of human connection.

Photography and cinema, Siegfried Kracauer observed, have a special power to portray happenstance. Often films, trying to use this power, spoil the effect with a certain portentousness: see Crash or the execrable 13 Conversations About One Thing. People encounter one another haphazardly, but random luck sends them in directions already meticulously charted: Initial conflict! Reluctant interpersonal perestroika! Self-discovery! Highly engineered “chance” and transparent moral messages tend to combine rather fretfully. The big problem is that “random encounters can affect people” is not a compelling insight, and seems only present as an excuse for Hollywood’s over-rationalized psychology of human connection.

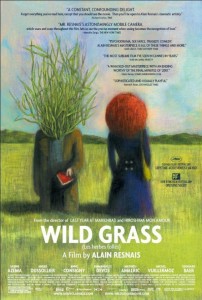

Instead of using happenstance as a pretext, Alain Resnais takes it as a philosophy. There is no real division of ordinary and unordinary. A chance encounter between two people may seem strange to them, but all of life is equally bizarre; it’s just that they’ve grown used to it. This, at least, is the most sense I could make of the story of Marguerite Muir and Georges Palet, the main characters of Wild Grass. Marguerite (Sabine Azéma) is a dentist and amateur aviatrix. Georges (André Dussollier), an eccentric older man with a wife, two grown children and a passion for planes, eventually finds her stolen wallet. After the return of the wallet, Georges becomes obsessed with the woman whom he knows only by her identity card and pilot’s license. By turns shy and scary, he at first provokes only her slightly pitying exasperation with bizarre, confessional letters and voicemails. But Marguerite, even after having called the police on him, suddenly changes her mind halfway through the film for reasons Resnais never quite lets us know. She madly dashes back into his life, seemingly desperate for contact, even befriending his astonishingly tolerant wife (Anne Consigny).

These characters may act oddly, but their real aura of strangeness lies more in Resnais’ distant approach to them than in their irrational acts. The first time we see Marguerite, the camera frames only her high-heel-shod feet while a voice-over narrator tells us that she’s on her way to buy shoes at her favorite store. Since she has extraordinary feet, she only frequents this particular store. Resnais continues to deny us her face even as the narrator describes her personality, but the camera does reveal her incredible, frizzy, near-maroon hair that seems to cushion her from the rest of the world.

The fateful moment arrives, in slow motion, with the snatching of Marguerite’s bright yellow purse. She throws up her hands in shock. We still cannot see her face–the camera tracks around with her as she turns her head–but the narrator reveals her internal reaction: she thinks of shouting, but “the words get stuck.” Life is like that, continues the narrator. The minor trauma of being robbed expresses the truth that, even dying, “we’re too scared to call out.”

This sequence demonstrates what you might call the film’s novelistic feel: it’s as though the real protagonist is an invisible reader, and the film represents the inside of his or her mind. Her face hidden, Marguerite might remain simply “the woman with red hair and extraordinary feet,” a stand-in or figment instead of an actual woman. Wild Grass is in fact based on a book by Christian Gailly. The novelistic approach extends throughout the film, even as the characters develop. Resnais borrows literature’s ability to express the protagonists’ thoughts directly: Marguerite and Georges’ voices occasionally join the mysterious voice-over narrator’s. Time and space elide–long a recognized capacity of film editing, but here especially effective in isolating our point of view from the characters’. Visually, we’re rarely allowed to share their perspective, despite having access to their thoughts.

From Wild Grass’s affinity with literature emerges a paradox that brings us back to happenstance. Are these characters, endowed with particularities like Azéma’s sensitive, hoarse voice or Dussollier’s shifty smile, meant to be “real” people, subject to random luck, or abstractions controlled by an author’s mind? Does their love of planes–and its connection to their eventual fate–represent the desire to escape ordinary life, or is such an interpretation a distraction from the simple idea that chance can knock our lives askew for no reason we can understand?

At the very least, the film’s expressionist use of color warns us not to take the plot too literally: the rich green light in Georges’ study, the neons in Marguerite’s bedroom, the unreal-looking blue Georges paints his house. And Resnais’ playful approach with the cinema’s conventional signs (for example, “The End” appears just before the film’s actual climax) suggests that he’s more concerned with how films work on the audience than with exploring character. The ambiguity can be somewhat frustrating at times, particularly at the film’s enigmatic ending, during which the camera suddenly travels to an unknown location to catch a surreal line spoken by a little girl who may or may not be Marguerite as a child.

But audiences who seek out a Resnais film probably know ahead of time that they will not be granted facile, cathartic riddles. If you can cope with the film’s slippery surface, its tricky beauty may stay in your mind longer than the unanswerable questions.

-Julia Zelman

One Comment

D.C. Douglas posted on November 25, 2010 at 6:01 am

Excellent review. One thing I would add for background, though, is how remarkable it is that an 87 year old directed it!