How many times have we seen this picture of the modern American West: kitschy, raunchy cities naïvely clinging on the edge of enormous, bare landscapes? The backdrop of Taylor Hackford’s Love Ranch is not unique in the movies; Nevada and California’s mountains and canyons, juxtaposed with a protagonist’s capitalist hubris, make for an instantly recognizable theme: the futility of trying to control one’s fate when the world is so unforgiving. But if Love Ranch, written by Mark Jacobson, starts off in this well-explored territory, some narratives are worth repeating–especially when the main character is not the little man fighting destiny, but this vain American dreamer’s tragically resigned, clear-sighted wife.

How many times have we seen this picture of the modern American West: kitschy, raunchy cities naïvely clinging on the edge of enormous, bare landscapes? The backdrop of Taylor Hackford’s Love Ranch is not unique in the movies; Nevada and California’s mountains and canyons, juxtaposed with a protagonist’s capitalist hubris, make for an instantly recognizable theme: the futility of trying to control one’s fate when the world is so unforgiving. But if Love Ranch, written by Mark Jacobson, starts off in this well-explored territory, some narratives are worth repeating–especially when the main character is not the little man fighting destiny, but this vain American dreamer’s tragically resigned, clear-sighted wife.

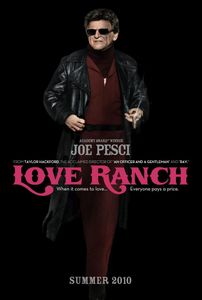

Helen Mirren plays Grace Bontempo, the madam of the Nevada brothel of the title. Her husband Charlie (Joe Pesci–what a co-star for the Queen of England!) co-owns the brothel and benefits from it far more than she does–taking from it 50% of the profits, sexual gratification in its bevy of tolerant girls, and most importantly a sense of self-worth. Through a combination of violence, political extortion and bargaining, Charlie has managed to force through the legalization of prostitution. He regards this as more than a practical gain; faking a Southwest accent, strutting around a cowboy tycoon–never mind that Grace has most of the brains and does most of the work–he can forget his beginnings as a small-timer “off the Jersey prairie,” as his wife sarcastically defines him.

Grace, for her part, reserves some stern affection for her rowdy girls, and handles the men (her husband as well as the customers) skilfully if without much pleasure. But early on in the film, she learns that she has cancer. She decides to keep this news from everyone, as always subordinating her own needs to the demands of business. Mirren shows Grace’s emerging bitterness without sentimental or self-pitying gestures: even facing death, Grace seems to assume that her feelings don’t interest anyone.

Then Charlie adopts a former boxing champion, a long-haired Argentinian named Armando Bruza (Sergio Peris-Mencheta). Charlie plans to invest in him for publicity’s sake and cajoles Grace into being his “manager.” The film’s publicity has made no secret that Love Ranch is a love triangle, so of course the audience knows that the handsome young boxer will convince sixty-year-old Grace to shed her apathy. But, thank the lord, the filmmakers depict the future lovers’ awkward first meetings as convincingly as their ardor later on. With his cheerful roar of a voice and huge grin, Bruza’s apparent clownishness renders the seduction improbable at first, as do Grace’s exasperation and confusion at his shambling friendliness.

Much of the film works this way: it presents us with situations we recognize from other movies, yet uses them as a springboard for genuinely thoughtful and persuasive performances. It’s as if, by some minor magic, clichés that sagged under thousands of lousy productions are suddenly nourished back to life by some terrific actors and a script that lets them act. Never mind that we’ve seen the sensitive, self-destructive boxer before. Love Ranch lets us believe in this one.

Bruza’s presence rebukes American capitalism, which the film associates with masculine bravado and violence. Americans like Charlie will offer him money, girls and stardom as long as he remains safely in the category of an investment. Not too subtly, the film shows that Charlie treats him just the same as the prostitutes–as flesh, a good “better than gold–you don’t have to get your nails digging for it, and the good Lord keeps making more of it.” The moment Bruza claims something beyond material appeasement–the right to return Grace’s love–his protectors start trying to destroy him.

Peris-Mencheta is so good, he doesn’t have to strain for attention alongside Helen Mirren, who for her part is absolutely free of the “grande dame” syndrome that sometimes overtakes renowned actresses playing world-weary unfortunates. And yes, they do have a sex scene together, one that will please the tender-hearted but not the prurient.

Cinematographer Kieran McGuigan makes the film look great, by turns gaudy, grubby and serene. No one has ever filmed white hooker boots in the mud so offhandedly and poetically. People’s faces look real and expressive–Mirren’s frank and sad, Peris-Mencheta’s warm and ruddy in the outdoor scenes, while Pesci, with his doggy jowls, is sadder and nastier than I’ve ever seen him.

Here is a film that happily plays with the elements of lurid melodrama, only to defy Grace Bontempo’s initial philosophy: “Selling love will make you rich. Just don’t put your heart in it.” Hollywood sells love too, but (on occasion) not without believing in it.

-Julia Zelman