If you’ve heard anything about Derek Cianfrance’s Blue Valentine, it was probably in the context of the MPAA’s laughable decision to stick the film with the dreaded NC-17 rating (since reversed to a still-too-harsh R), or maybe you have a bearded, plaid-loving friend who keeps gushing about Grizzly Bear writing the film’s score (as a Grizzly Bear fan, I can say that this is, at the very least, just as cool as Daft Punk scoring Tron), but what you really should know is that it is the best American film of 2010 (so far). I want to clear up the MPAA issue early, so I can devote the rest of this article to the film itself. There is nothing, and I mean absolutely nothing, in this film that comes even remotely close to deserving the NC-17 rating, which would mean a virtual ban from theaters and from television advertising. There are a few moments of nudity, occasional cursing and a more realistic view of sexuality than you’d find in a PG film, but if you had told me that it was rated PG-13, I would not have been that surprised. The only offensive thing here is that an organization as contradictory and backward thinking as the MPAA is still allowed to have such an impact on what movies we see in America.

If you’ve heard anything about Derek Cianfrance’s Blue Valentine, it was probably in the context of the MPAA’s laughable decision to stick the film with the dreaded NC-17 rating (since reversed to a still-too-harsh R), or maybe you have a bearded, plaid-loving friend who keeps gushing about Grizzly Bear writing the film’s score (as a Grizzly Bear fan, I can say that this is, at the very least, just as cool as Daft Punk scoring Tron), but what you really should know is that it is the best American film of 2010 (so far). I want to clear up the MPAA issue early, so I can devote the rest of this article to the film itself. There is nothing, and I mean absolutely nothing, in this film that comes even remotely close to deserving the NC-17 rating, which would mean a virtual ban from theaters and from television advertising. There are a few moments of nudity, occasional cursing and a more realistic view of sexuality than you’d find in a PG film, but if you had told me that it was rated PG-13, I would not have been that surprised. The only offensive thing here is that an organization as contradictory and backward thinking as the MPAA is still allowed to have such an impact on what movies we see in America.

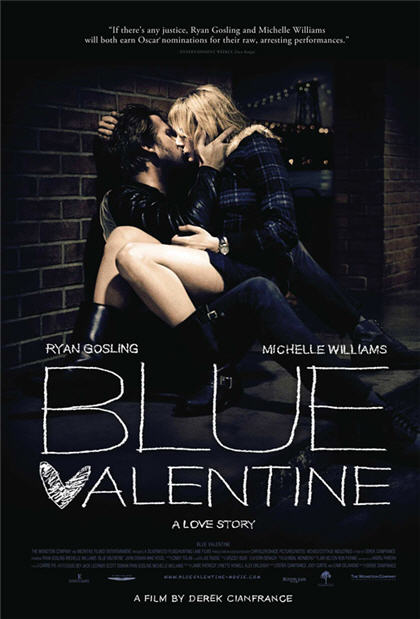

Ryan Gosling and Michelle Williams play Dean and Cindy, a married couple at the end of their relationship. They have a daughter, and they’ve likely stayed together so long because of her, but the film follows the final events leading to the dissolution of their marriage, interspersed with flashbacks to their first meeting and other major events. It opens at their rural home, as the clearly strained family tries to find their missing dog, a search that does not end well. Cindy and Dean both clearly love their daughter, but it’s quite clear from the opening scene that something is wrong with their relationship. When they met in Brooklyn, Cindy was an idealistic med student and Dean was a goofy, but artistically talented and charismatic, mover who meets Cindy in a nursing home. In the flashbacks, we follow them from the first date through their marriage, and it is through these scenes that we understand why their relationship failed. Cindy’s parents and grandparents all suffered through lifelong loveless relationships, turning her against the whole idea. Dean’s mom left when he was a kid, and he just wants to find something to love that he can hold on to for the rest of his life. Between the day they were married (the end of the flashbacks) and the one brutal day that makes up the present in the film, we have to infer that things have gone wrong. Dean’s potential has led nowhere, he paints houses, but he, at least, is happy because the job allows him to spend time with his family. Cindy has failed as a doctor and now earns her living as a very stressed nurse. She is miserable because all of the promise they once had is seemingly gone, and she cannot accept her current lifestyle. She runs into an ex on the way to the one-night motel where Dean is trying to save the marriage, and she tells him that she’s “been here, stayed here, never left here,” the bitterness in her tone explaining everything you need to know about her situation.

Now, because of the temporally shifting romance and breakup and the hipster-friendly soundtrack, some have seemingly been compelled to compare it to last year’s 500 Days Of Summer, which is a disservice. I enjoyed that film for what it was, but Blue Valentine is a far better film in nearly every regard. Not only is it a better looking movie with some of the most realistic and frank dialogue in any film you’ll ever see instead of the annoyingly twee indie-speak that replaced human dialogue in the other film, but it features two of the best actors of our generation at the absolute peak of their respective careers. Most of Cindy and Dean’s problems, at least early in the film, are not outwardly articulated, but the two stars bring such an impressive degree of emotional intensity to their roles that all of their issues are completely clear. Each deserves every award-season accolade that they will no doubt receive in the next few months, but credit also has to go to the director. Cianfrance’s use of hand-held cameras and the film’s extreme emotional intensity will undoubtedly draw well-deserved comparisons to Cassavetes (and maybe some will note the irony that Gosling’s big break came in a pretty lousy film directed by the indie god’s actual son). Visually, Blue Valentine is quite pleasing, with very strong colors and a near-constant shallow focus, usually leaving only one character in the foreground. Notably, the constant shaky cam never gets in the way of the composition, which in my mind is the biggest risk directors run when they use that technique. The most important aspect of the film is the level of emotional rawness present in every single scene. Even though it spends roughly two hours focused on these two people, it never grows boring because every scene is cackling with energy, the result of a truly talented young director working with a really wonderful cast. The music by Grizzly Bear adds another layer of brilliance to the film, perfectly accentuating every scene in which it is used, but never calling too much attention to itself. Much of the score is made from pieces of their older songs, particularly “Foreground,” which serve the film’s mournful tone and Brooklyn setting quite well. I believe there were a few new pieces in there, but those expecting a new album’s worth of material may leave disappointed. I was quite satisfied with the music, and for my money, the only way they could have improved the score to Blue Valentine would have been to throw in some tracks off of the underrated Tom Waits album of the same name, which probably would have fit pretty well amidst all the melancholy.

Most films dealing with divorce tend to take one side of the issue. It’s not always a conscious decision by the writer or director, but you can always see that one side is being presented as “right” and the other as “at fault.” To use an example I watched recently, in Redford’s Ordinary People, there is some discussion of the Donald Sutherland character’s problems, but in the end almost all of the blame is laid at the feet of Mary Tyler Moore’s character. Neither is a particularly deep personality, which allows the director and audience to simply go with their surface criticisms of the wife. In Blue Valentine, both characters are so complex and well-rounded that Cianfrance is actually able to avoid this classic problem by making his audience understand that nobody is completely at fault, and that the forces of the outside world and the American dream can cause the end of even the most loving relationship. In doing so, he questions the possibility of the long-term relationship in today’s world. There is not a single example of a working, happy couple on screen except for the flashbacks of Dean and Cindy. At the very least, it seems to encourage the philosophy that marriage is an archaic institution that does not work today. Or maybe, to quote the song Dean sings on the first date, it is saying, “You always hurt the ones you love,” and that love is an inherently painful process, but there is something good in the end. Either way, this is an emotionally gripping, aesthetically impressive tour de force that should not be missed when and if it comes to your city.

-Adam Burnstine

Blue Valentine is rated R for “Strong graphic sexual content (which doesn’t actually exist in the film), language (minimal) and a beating (there are about six punches thrown total, and there is no violence against women).”

It opens in New York and LA on December 31st, and will come out in Boston some time in January.

Directed by Derek Cianfrance; written by Derek Cianfrance, Joey Curtis and Cami Delavigne; director of photography, Andrij Parekh, edited by Jim Helton and Ron Patane; music by Grizzly Bear; art director, Chris Potter; produced by Ryan Gosling, Michelle Williams, Lynette Howell, Alex Orlovsky and Jamie Patricof; distributed by The Weinstein Company; run time 2 hours.

With: Ryan Gosling (Dean), Michelle Williams (Cindy), Faith Wladyka (Frankie), John Doman (Jerry), Mike Vogel (Bobby) and Ben Shenkman (Sam Feinberg).