Every Jane Austen fan remembers her first time. Reading Pride and Prejudice, that is. Still I’ll never forget the first time I saw the BBC TV mini-series of Pride and Prejudice, the 1995 Simon Langton version so perfectly executed that the film adaptation gods must have wept when they watched it. Days later, I popped my mother’s copy of the 1940 Robert Leonard adaption into the VCR, anxious to watch the great Laurence Olivier in the role of my latest favorite fictional fella, Mr. Darcy. But Olivier’s portrayal sent me running back into the arms of my beloved BBC version, desperate to find the name of the actor that made Olivier look like a wuss. Who was the actor that made one of the most distinguished British actors of history appear as a weak and timid sap? It was Colin Firth.

Every Jane Austen fan remembers her first time. Reading Pride and Prejudice, that is. Still I’ll never forget the first time I saw the BBC TV mini-series of Pride and Prejudice, the 1995 Simon Langton version so perfectly executed that the film adaptation gods must have wept when they watched it. Days later, I popped my mother’s copy of the 1940 Robert Leonard adaption into the VCR, anxious to watch the great Laurence Olivier in the role of my latest favorite fictional fella, Mr. Darcy. But Olivier’s portrayal sent me running back into the arms of my beloved BBC version, desperate to find the name of the actor that made Olivier look like a wuss. Who was the actor that made one of the most distinguished British actors of history appear as a weak and timid sap? It was Colin Firth.

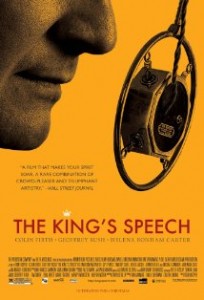

Since the late 1990s, Firth has been one of the most popular British actors in film, despite never being in a Harry Potter movie. His first film credit was in 1984 for a role in Another Country, but he didn’t really make his mark until 1995, over a decade later, when he landed his first role as Mr. Darcy. After that, Firth was popping up all over the place—Circle of Friends, The English Patient, Shakespeare in Love—but always as a supporting character. Now, at 50, he is finally receiving more attention as a leading actor, which begs the question: why now? In 2010, Firth was nominated for an Oscar for Best Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role for his portrayal of George Falconer in A Single Man. Last month, Entertainment Weekly named him “the man to beat,” expecting him to receive his second Oscar nod in two years for his role as King George VI in The King’s Speech. Perhaps it would be an overstatement to claim that Firth has been overlooked in the past; he has certainly had his share of flops (Mamma Mia! and The Accidental Husband come to mind). Nevertheless, Firth’s recent film choices suggest that not only is he “the man to beat,” he is the man to keep an eye on.

Pride and Prejudice was the film that established Colin Firth’s star persona—serious, proud, intellectual, dignified, even snobbish. Unsurprisingly (or consequently), his film characters often share these same qualities—Simon Westward in Circle of Friends, Geoffrey Clifton in The English Patient, Lord Wessex in Shakespeare in Love, Henry Dashwood in What A Girl Wants, and Richard Bratton in The Accidental Husband. His role as Mark Darcy in Bridget Jones’s Diary and Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason merely updated Mr. Darcy’s character to the 21st century (just as Renee Zellweger brought Elizabeth Bennet to 2001 London). Colin Firth doesn’t just play Mr. Darcy; he is Mr. Darcy, and perhaps his recent film choices are reflecting a desire to separate himself from the character.

In A Single Man (directed by Tom Ford), Firth brilliantly plays the polished and intellectual George Falconer, an English college professor who must cope with the death of his much younger partner. In a departure from his typical roles (this is definitely one of his riskier films), Firth perfectly captures the heartrending truths of mourning and grief. Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly, in his review of A Single Man, put into words what the rest of the film-going world was thinking: “Colin Firth is an intensely likable actor, but in every movie I’ve ever seen him in he is always…Colin Firth, witty, diffident, with that resignation hanging over his every grin and grimace. In A Single Man, though, I felt as if I were seeing him for the first time.” With 2008’s Mamma Mia! still fresh in our memories, we were shocked by his nuanced performance of a homosexual man in 1962 America.

More than just a film about a grieving man, A Single Man provides social commentary of an “invisible minority.” After the sudden death of his partner, George realizes that he has no other real relationships (this is the 60s, he can’t just announce to the world that he’s gay), and even his great friendship with Charly (played by the remarkable Julianne Moore) is full of tension. The film’s comparatively little dialogue merely allows Firth to embody the character more fully, and we see his Oscar-worthy acting in the subtle changes of his expressions and in the delicate care George takes in preparing for his suicide.

Without question, A Single Man was a giant step in the right direction for Firth, if he was seeking an Oscar. The subtle and artistic film is a kind of second arrival on the film scene for Firth, who was in many ways resting on Mr. Darcy’s laurels from Pride and Prejudice and both Bridget Jones films. In fact, George Falconer could not be any more different from Mr. Darcy, except, perhaps, in his love of literature. So we must ask, have we become so used to Firth playing Mr. Darcy that anything new is refreshing?

The King’s Speech is refreshing, not just for Firth, but for all film audiences accustomed to the cold portrayals of British royalty. The film (directed by Tom Hooper) takes us back to England in the years between World Wars I and II. Thanks to radio, monarchs and political leaders can no longer sit in an office to rule the world in peace; they must regularly address world through radio broadcasts. The film begins as the Duke of York (Colin Firth) addresses a large stadium on behalf of his father, King George V. Public speaking is not his forte, not because of fear of an audience, but because of an unconquerable stutter. The subject of his speech is irrelevant; no one can focus on anything other than the stammer. The echo in the arena only exaggerates his stutter, sounding mercilessly like sinister laughter.

Despite countless attempts to overcome his speech impediment, the Duke (lovingly called Bertie by his family and speech therapist) resigns himself to the fact that he will always have a stammer. This truth does not signify too much, since Bertie believes that he is safely beyond the chance of ever becoming king (his older brother, Edward, is next in line). But after his father’s death and his brother’s abdication (the film surpasses Wikipedia as a brief history lesson of British government), Bertie finds himself in the unexpected role of king and must rely more heavily on his unconventional speech therapist to present himself as an image of authority in the early days of World War II.

The King’s Speech deserves academy recognition solely because it is one of the few films this year that is devastatingly beautiful to look at, with its gorgeous pale blues and greens and the elegant set design of the palaces. The supporting cast, which includes Geoffrey Rush (as the speech therapist Lionel Logue) and Helena Bonham Carter (as Queen Elizabeth), superbly balances the drama and humor of the film. But the bulk of the praise must go to Firth, who takes possession of his role—indeed takes possession of the whole film—in a way that he has not done in any of his earlier work. More than anything else, he brings humanity to the royal family (even more than Helen Mirren in The Queen), comprehending Bertie’s roles as husband, father, Duke, and eventually king.

Firth effortlessly controls his performance, avoiding the traps of schmaltz and dramatic overkill. He does not over-play the heartbreaking moments of the film (which of course makes these scenes even more tragic), such as when he struggles to tell his daughters a bedtime story or when he sings about how he was abused by his nanny (Logue encourages Bertie to sing his sentences to defeat his stutter). Throughout the film, Logue insists that he and his patients must be equals in order for his methods to work. But in the course of the story, Bertie (and by extension Firth) becomes our equal, allowing us to see the British king as an authentic, sympathetic, and human character. If Firth doesn’t win the Oscar for that, then the academy will be hearing from me.

So what makes Firth the new leading-man of choice for films about middle-aged men? Well, for starters, he is still very popular with the female audiences. Second, despite his flops, Firth has proven that he can handle different kinds of roles, from serious parts (Girl With the Pearl Earring) to funny roles (The Importance of Being Ernest) to characters in children’s films (Nanny McPhee). Firth himself weighed in on the question during an interview with Entertainment Weekly’s Dave Karger (who described the actor as “the thinking woman’s heartthrob”), stating, “The stories about men my age are rather interesting. They have a past. Maybe I’ve been given an opportunity which has perhaps invited me to raise my game.”

We can expect to see Firth raising his game and exercising his versatility in his upcoming thrillers of 2011, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and The Promised Land (where he will work with fellow Mr. Darcy, Matthew MacFayden). More importantly, we can see Firth in the roles of writer, director, and producer in his 2010 documentary The People Speak UK, a film about various moments of dissent and rebellion in British history. At an age when most actors are slowing down and taking on less roles, he is expanding into various aspects of the film industry. Nevertheless, we can look forward to great things from the actor, as long as he continues to challenge himself with complex, humanist roles. Now, if only I could look beyond Firth as Mr. Darcy in his more recent films: Mr. Darcy as spy, Mr. Darcy as king, Mr. Darcy as ABBA fanatic.

Directed by Tom Hooper; written by David Seidler; director of photography, Danny Cohen; edited by Tariq Anwar; original music by Alexandre Desplat; production design by Eve Stewart; produced by Iain Canning, Emile Sherman and Gareth Unwin; released by the Weinstein Company. Running time: 1 hour 58 minutes.

With: Colin Firth (King George VI), Geoffrey Rush (Lionel Logue), Helena Bonham Carter (Queen Elizabeth), and Guy Pearce (King Edward VIII).

Review by Melissa Cleary