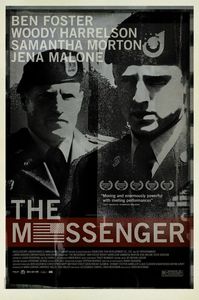

Maybe it was wrong of me, but for a minute there, I really thought that we would get a second great film dealing with the war in Iraq this year, which would of course bring the total number of great films dealing with the war in Iraq up to two. Unfortunately, The Hurt Locker must remain alone on that list, as Oren Moverman’s The Messenger may not be a bad film, but it just isn’t that good. I’m not sure why I expected something more, given the rather pathetic history of films dealing with Iraq, and the fact that it is Moverman’s first film as a director, but he did co-write Todd Haynes’s brilliant I’m Not There. Plus, the cast includes Ben Foster, Woody Harrelson, Samantha Morton and Steve Buscemi, all of whom have done great work in the past. The film was praised coming out of Sundance (even though that really doesn’t mean a thing anymore), and it won a Silver Bear at Berlin for best screenplay. Unfortunately, all it amounts to is an inconsistent, shallow, cliché mess with a few bright spots.

Maybe it was wrong of me, but for a minute there, I really thought that we would get a second great film dealing with the war in Iraq this year, which would of course bring the total number of great films dealing with the war in Iraq up to two. Unfortunately, The Hurt Locker must remain alone on that list, as Oren Moverman’s The Messenger may not be a bad film, but it just isn’t that good. I’m not sure why I expected something more, given the rather pathetic history of films dealing with Iraq, and the fact that it is Moverman’s first film as a director, but he did co-write Todd Haynes’s brilliant I’m Not There. Plus, the cast includes Ben Foster, Woody Harrelson, Samantha Morton and Steve Buscemi, all of whom have done great work in the past. The film was praised coming out of Sundance (even though that really doesn’t mean a thing anymore), and it won a Silver Bear at Berlin for best screenplay. Unfortunately, all it amounts to is an inconsistent, shallow, cliché mess with a few bright spots.

Ben Foster plays Sgt. Will Montgomery, who has been injured in Iraq, and ordered to spend the final three months of his enlistment as a casualty notification officer teamed up with Captain Tony Stone (Harrelson). They both have to deal with their own emotional traumas, and Montgomery’s are complicated when he begins to fall for Olivia (Morton), one of the widows with whom he must speak. Even though I called it a film dealing with the war in Iraq, there are no battles in this film. Every scene takes place back in America as the three main characters struggle to come to terms with everything that has happened in their lives. Foster is perhaps best known for his great role as a sociopathic killer in the otherwise insipid 3:10 To Yuma remake. This is his first major starring role, and while I wish he had been a bit less reserved at certain moments, he does a fine job. Harrelson essentially plays a less funny version of the same falsely jaded character he did in Zombieland, but it works in this film. He brings just the right combination of audaciousness, humor and poignancy to create a good character. Stone tries to get by on fortune-cookie philosophy and a false tough-guy act (he says, “We’re just there for the notification. Not God. Not Heaven”), but throughout the film, cracks in his armor begin to form, and the job, considered by many to be the worst in the army, begins to take its toll. Unfortunately, the usually great Morton is given a role that nobody could work with. The writers try to have her character use whatever simple language they expect out of an army wife, but they still have her make big speeches with complex ideas. The worst example of this is late in the film, as Olivia and Will begin talking about her late husband, and how he had changed when he first came home from Iraq, before reenlisting. The writers try to get across complex ideas on the horrors of war through dialogue that essentially breaks down to “he was real mean to us,” and it comes off as forced and silly. Ultimately, through these characters, the film tries to achieve a lot, but does not succeed. Some ideas are just underdeveloped, such as the motivation of the soldiers and the grief of the families they meet, while others have been explored in better films before, especially the role of the individual and his or her emotions vs. procedure. This last one is arguably the main theme of the film, but they get it across in cliché dialogue along the lines of “You didn’t follow procedure!” “Oh yeah, well fuck procedure.” The film awkwardly jumps through various storylines (Will and his ex, Tony’s alcoholism, Olivia and her son, Will and Olivia’s relationship, Will and Tony’s friendship, etc), each one with a different tone and rarely coming together. Will is the center of it all, and even though Foster is pretty good, he is not a strong enough character to bring a real sense of cohesion to the film as a whole.

As Montgomery and Stone make their trips, the moments of sadness begin to pile on top of each other in what eventually becomes little more than a montage of grief. Of the dozen or so notifications that we see, you may remember that one was in Spanish, or one was a father and daughter or a husband and wife, but only two of them stick out with any detail. The rest are the same screams and the same nameless loved ones. I’d say this was an intentional decision to explore the casualty team’s job a bit further, but during these scenes Moverman switches to a hand-held camera, which becomes nothing more than a cheap way to try to manipulate the emotions of the audience. Morton’s first scene sticks out because she does not start screaming and she becomes a major character later. The other noteworthy one, which is undoubtedly the highlight of the film, features Steve Buscemi in a cameo as a father who gets angry at the officers. Despite only having a few minutes of screen time, he gives the best performance of the film, because his anger and his emotions feel much more real than anyone else’s. The notification scenes could have given a full, deep picture of the spectrum of human emotion, but Moverman chose to make most of them the same and he achieves nothing more than simple manipulation. I found the shifts in camera-movement particularly bothersome. It has become a trend in recent years to use a shaky camera to punctuate emotional moments by adding a hint of realism, but, unless it’s used throughout an entire film (Rachel Getting Married), it generally comes off as a way to add extra emotion to a scene that doesn’t entirely work on its own. In a film that already features a story that fluctuates in tone, it adds an extra degree of annoying tonal inconsistency. While the film does have a few good features, including the decision to remain politically neutral, which is vital in a story about people rather than ideas, these tonal inconsistencies and obvious manipulations lead to an emotional shallowness that prevent it from aspiring to anything above mediocrity.

-Adam Burnstine

The Messenger is rated R for language and some sexual content/nudity

Opens at the Kendall Square Cinema in Cambridge November 20th 2009

Directed by Oren Moverman; written by Oren Moverman and Alessandro Camon; director of photography, Bobby Bukowski; edited by Alexander Hall; original music by Nathan Larson; production designer, Stephen Beatrice; produced by Benjamin Goldhirsh, Mark Gordon, Lawrence Inglee and Zach Miller; released by Oscilloscope Laboratories. Running time: 1 hour 45 minutes.

WITH: Ben Foster (Staff Sergeant Will Montgomery), Woody Harrelson (Captain Tony Stone), Samantha Morton (Olivia Pitterson), Jena Malone (Kelly), Eamonn Walker (Colonel Stuart Dorsett) and Steve Buscemi (Dale Martin).

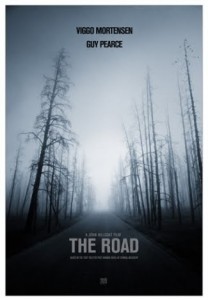

The official trailer for the film The Road scared me more than any horror film released this year. As a fan of Cormac McCarthy’s Pulitzer Prize winning post-apocalyptic novel, the rapid images of Earth’s demise and destruction intercut with a father and son fighting against the evil villains to survive in this new world are a far cry from the bleak yet touching story that brought tears of both joy and sadness to so many readers. (To see what I’m talking about, check out the trailer at:

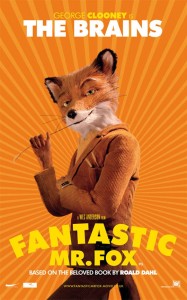

The official trailer for the film The Road scared me more than any horror film released this year. As a fan of Cormac McCarthy’s Pulitzer Prize winning post-apocalyptic novel, the rapid images of Earth’s demise and destruction intercut with a father and son fighting against the evil villains to survive in this new world are a far cry from the bleak yet touching story that brought tears of both joy and sadness to so many readers. (To see what I’m talking about, check out the trailer at:  At some point along the line, we all sort of knew Wes Anderson was going to try to make an animated kid’s movie. The set design and inserts from The Royal Tenebaums and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou all seemed like pastel throw-ins from Blue’s Clues. All of Anderson’s characters, from Max Fischer down to Francis from The Darjeeling Limited, exhibit the listless naivety of youth that comes from being a child or wishing to be one again. But given the somewhat more mature Darjeeling, it should be some sort of surprise that The Fantastic Mr. Fox is a work of stop-motion beauty, capitalized by a not-so-kid-friendly script adapted from Roald Dahl’s book of the same name.

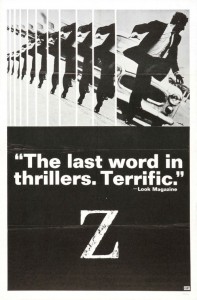

At some point along the line, we all sort of knew Wes Anderson was going to try to make an animated kid’s movie. The set design and inserts from The Royal Tenebaums and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou all seemed like pastel throw-ins from Blue’s Clues. All of Anderson’s characters, from Max Fischer down to Francis from The Darjeeling Limited, exhibit the listless naivety of youth that comes from being a child or wishing to be one again. But given the somewhat more mature Darjeeling, it should be some sort of surprise that The Fantastic Mr. Fox is a work of stop-motion beauty, capitalized by a not-so-kid-friendly script adapted from Roald Dahl’s book of the same name. One of the crucial lessons of 20th century politics is that authoritarianism is unsustainable in the long run, because people are naturally inclined to be free and the information that will allow them to be free will eventually, inevitably leak out. One or two people might be able to keep a secret, but an entire government cannot. The “9/11 Truth Movement” is ludicrous for that reason, as is the recent “Birther” phenomenon and the more fantastical theories regarding the Kennedy assassination. Truth might be stranger than fiction, but when it comes to government, usually the simplest explanation is the correct one.

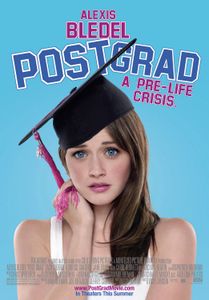

One of the crucial lessons of 20th century politics is that authoritarianism is unsustainable in the long run, because people are naturally inclined to be free and the information that will allow them to be free will eventually, inevitably leak out. One or two people might be able to keep a secret, but an entire government cannot. The “9/11 Truth Movement” is ludicrous for that reason, as is the recent “Birther” phenomenon and the more fantastical theories regarding the Kennedy assassination. Truth might be stranger than fiction, but when it comes to government, usually the simplest explanation is the correct one. The unemployment rate is expected to hit 10% this year. Companies and consumers are buckling down to spend less---meaning less job opportunities, fewer benefits, and lower salaries. Not a great time for young college graduates. The immediate future is a bleak and scary place, filled with endless interviews, student loan payments, and no silver lining on that college diploma. Just don’t tell that to the makers of Post Grad.

The unemployment rate is expected to hit 10% this year. Companies and consumers are buckling down to spend less---meaning less job opportunities, fewer benefits, and lower salaries. Not a great time for young college graduates. The immediate future is a bleak and scary place, filled with endless interviews, student loan payments, and no silver lining on that college diploma. Just don’t tell that to the makers of Post Grad.