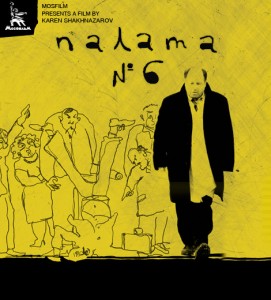

I first discovered the work of Karen Shakhnazarov last year during an MFA retrospective on his work. On a whim, I decided to go to a screening of his film Gorod Zero, a great decision for two reasons: First, the Kafkaesque study of Russia’s modernization is now one of my favorite films of the 1980s, and second, Shakhnazarov himself was there, taking questions. Even though I was one of the few non-Russian speakers in the audience and couldn’t understand everything, it did help me realize that Shakhnazarov, now the director of Russia’s powerful Mosfilm studios, is a man who loves to play with expectations and subvert traditional means of storytelling, something he does wonderfully in his new film, Ward No. 6, co-directed with Aleksandr Gornovsky, based on a great short story by Anton Chekhov and Russia’s official submission to the academy awards this year. The script for this project has been floating around for decades with any number of filmmakers, from Russia and beyond, attached and actors from all over, including the great Marcello Mastroianni, set to take the lead role, eventually filled by Vladimir Ilyin. Chekhov’s original is one of my favorite short stories, and I’m proud to say that this is as good adaptation as one could expect.

I first discovered the work of Karen Shakhnazarov last year during an MFA retrospective on his work. On a whim, I decided to go to a screening of his film Gorod Zero, a great decision for two reasons: First, the Kafkaesque study of Russia’s modernization is now one of my favorite films of the 1980s, and second, Shakhnazarov himself was there, taking questions. Even though I was one of the few non-Russian speakers in the audience and couldn’t understand everything, it did help me realize that Shakhnazarov, now the director of Russia’s powerful Mosfilm studios, is a man who loves to play with expectations and subvert traditional means of storytelling, something he does wonderfully in his new film, Ward No. 6, co-directed with Aleksandr Gornovsky, based on a great short story by Anton Chekhov and Russia’s official submission to the academy awards this year. The script for this project has been floating around for decades with any number of filmmakers, from Russia and beyond, attached and actors from all over, including the great Marcello Mastroianni, set to take the lead role, eventually filled by Vladimir Ilyin. Chekhov’s original is one of my favorite short stories, and I’m proud to say that this is as good adaptation as one could expect.

The film begins with a series of interviews with patients in a real Russian mental institution. These interviews are somewhat unsettling as it is never made explicitly clear who is an actual patient and who is an actor. We then get a cinema-verite style sequence in which the new doctor at the head of the facility (this time an actor) leads us around before introducing the main story, about the downfall of his predecessor, Dr. Ragin (Ilyin). Ilyin is wonderfully pathetic as the old doctor. His lack of a true moral center is well-portrayed without worthless exposition. The rest of the film is split between verite footage of Ragin and his former friends in the present, archival “home-video” footage of him in the past and traditionally filmed sequences of him in the past. The archival footage mainly comes from the camera of his friend Mikhail, whom the doctor considers the only other intellectual in town. This footage includes a trip to Moscow that Ragin clearly has no interest in. The shots of endless traffic and tourist areas are backed up by an ironic up-tempo jazz score that gets kind of annoying after the first minute. The traditional sequences generally involve Ragin’s philosophical discussions with Gromov (Aleksei Vertkov, who is excellent in the role), one of the patients. Ragin is sane, and he argues for an impractical stoicism, but the insane Gromov argues for a more realistic view on life. Eventually, Ragin’s friends begin to question their relationship and the doctor himself is thrown into the asylum, where he lapses into silence following a stroke.

Chekov’s story follows a similar pattern. In the beginning, he explains the backgrounds of the other patients on the ward, before focusing on the doctor’s story, and I thought Shakhnazarov’s way of echoing this technique was absolutely brilliant. The mental patients being filmed (some real, some actors) all have one goal: to escape the institution, but their varying degrees of eloquence and sanity make them more interesting, and the patients interviewed at the beginning pop up in the background throughout the film. The whole thing was filmed in a real psychiatric ward, and throughout the film, as the characters walk around the ward, real mental patients look up and follow them, creating a disturbing realism. Shooting in a real Russian mental hospital limits the aesthetic possibilities, so the realistic documentary-style camera movement works best. Even though the building was originally built as a monastery, the interior is made up in the standard bleak Soviet utilitarian style, which means the film is drenched in grays and other drab colors, adding to the realism, while limiting the lighting and color schemes.

The biggest difference between the story and the film comes from the setting. Chekhov wrote his version in 1892, under the pre-revolutionary terror of the tsars, while the film is set in the dreary, empty modern countryside of post-Communist Russia. Instead of living in total fear, the people live in a state of dreary ennui. This is reflected by the changed ending of the film. The book ends with nothing but despair. The film, on the other hand, is a bit more ambiguous. First, there is a brilliantly absurd dance sequence involving patients from the men’s and women’s wards which would have fit right into a Bela Tarr film, and then there is a final interview with Dr. Ragin’s neighbors, and a hauntingly ambiguous final shot of two children that he helped out. Also, in the original story, Chekhov explains much more about Ragin’s past, and he becomes a more sympathetic character. The film is barely even 80 minutes long, so it is much harder to truly care for his plight. Rather, his story must be seen as a means of creating interesting conversations and getting ideas across.

Aside from the conversations on the meaning of life, which are more of a surface level distraction designed to build the relationship between Ragin and Gromov, the film’s main purpose is to study the thin, blurred line between sanity and insanity. Gromov has a persecution complex, which he fully admits to, but Ragin’s illness is never made clear. He is thrown into the asylum, seemingly only because he has lost interest in the people around him, something that is made much clearer in the original story. Ragin’s replacement says, early in the film, “incidentally, the borderline between psychotic and normal people is pretty illusory.” We have an idea as to why others thing Ragin is insane, but we have no idea whether or not they are correct. On the other hand, Nikita, the head guard, beats the inmates and shows no care for their health and safety. What makes him sane? The invisible line is what makes the film interesting. Are people all the same and is it just random that one person is a doctor and another is a patient, or is that line something clear and tangible that separates the sane and the insane? Overall, while there are certain aspects of Chekhov’s work that I would like to see put in here, this is a worthy adaptation of a great story that works perfectly well on its own.

-Adam Burnstine

Ward No. 6 is unrated and in Russian with English subtitles

It begins a limited run at the Boston Museum Of Fine Arts on January 27th

Written and directed by Karen Shakhnazarov and Aleksandr Gornovsky; based on a short story by Anton Chekhov; director of photography, Aleksandr Kuznetsov; edited by Irina Kozhemyakina; original music by Evgeny Kadimsky; production designer, Lyudmila Kusakova; produced by Karen Shakhnazarov; released by Mosfilm. Running time: 1 hour 23 minutes.

With: Vladimir Ilyin (Ragin), Aleksei Vertkov (Gromov), Aleksandr Pankratov-Chyorny (Mikhail Averyanovich), Yevgeni Stychkin (Kobotov) and Viktor Solovyov (Nikita).

Mexican artist Damien Ortega’s first comprehensive exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, leaves the visitor a little giddy, as art objects are both literally and metaphorically suspended within the galleries. Material presence seems to be in a state of hanging, suspension, and unsteadily balance. Objects, visitors, artistic concepts, theories and ideologies seem to be held in a state of abeyance.

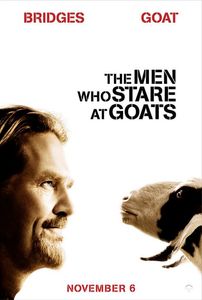

Mexican artist Damien Ortega’s first comprehensive exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, leaves the visitor a little giddy, as art objects are both literally and metaphorically suspended within the galleries. Material presence seems to be in a state of hanging, suspension, and unsteadily balance. Objects, visitors, artistic concepts, theories and ideologies seem to be held in a state of abeyance. In his seminal essay “Bad Movies” J. Hoberman writes that really “bad” movies are not without merit and that “it is possible for a movie to succeed because it failed.” However, sometimes movies come around that are not just bad but something much worse. They are entirely middling. Such is the case with Grant Heslov’s The Men Who Stare at Goats.

In his seminal essay “Bad Movies” J. Hoberman writes that really “bad” movies are not without merit and that “it is possible for a movie to succeed because it failed.” However, sometimes movies come around that are not just bad but something much worse. They are entirely middling. Such is the case with Grant Heslov’s The Men Who Stare at Goats. Unfortunately, I am nowhere near as familiar with the works of Leo Tolstoy as I’d like. I’ve been meaning to read War And Peace for years, but it’s hard to find the time. Thankfully, if nothing else, The Last Station, Michael Hoffman’s film on the final year of Tolstoy’s life, only covers Tolstoy as a man and a symbol, and knowledge of his work as an artist isn’t entirely necessary to understand the film. Tolstoy was a fascinating man, an aristocrat who turned on his heritage to write the most beloved examples of realist literature and spent the end of his life building the Tolstoyans, a cult of anarchistic non-violent resistance. A full biopic, like a full film version of War And Peace would be extraordinarily difficult and very unwise (I’m aware that the 1968 Soviet version of the novel is considered a classic, but it is also eight hours long and, adjusting for inflation, cost the equivalent of $700 million). Hoffman’s decision to only concentrate on the author’s final months and his relationships with his wife and close friends was a good one, as were the decisions to cast Christopher Plummer, Helen Mirren and Paul Giamatti in the main roles. Unfortunately, those are the only really good decisions evident in the final version, yet another well-acted, but by-the-book historical biopic that seems out of date after 2009’s radiant Bright Star proved just how great the genre could be.

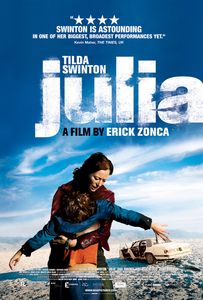

Unfortunately, I am nowhere near as familiar with the works of Leo Tolstoy as I’d like. I’ve been meaning to read War And Peace for years, but it’s hard to find the time. Thankfully, if nothing else, The Last Station, Michael Hoffman’s film on the final year of Tolstoy’s life, only covers Tolstoy as a man and a symbol, and knowledge of his work as an artist isn’t entirely necessary to understand the film. Tolstoy was a fascinating man, an aristocrat who turned on his heritage to write the most beloved examples of realist literature and spent the end of his life building the Tolstoyans, a cult of anarchistic non-violent resistance. A full biopic, like a full film version of War And Peace would be extraordinarily difficult and very unwise (I’m aware that the 1968 Soviet version of the novel is considered a classic, but it is also eight hours long and, adjusting for inflation, cost the equivalent of $700 million). Hoffman’s decision to only concentrate on the author’s final months and his relationships with his wife and close friends was a good one, as were the decisions to cast Christopher Plummer, Helen Mirren and Paul Giamatti in the main roles. Unfortunately, those are the only really good decisions evident in the final version, yet another well-acted, but by-the-book historical biopic that seems out of date after 2009’s radiant Bright Star proved just how great the genre could be. Erick Zonca’s Julia is a rare type of film, one that works largely in spite of its own script. Yes, it is twenty minutes too long, needlessly convoluted and it ends poorly, but through a combination of fantastic acting and some beautiful photography, it somehow finds a way to succeed. The film starts Tilda Swinton as a desperate southern California alcoholic who finds herself wrapped in a plot to kidnap the long-lost son of a casual acquaintance from his wealthy grandfather, but soon takes matters into her own hands in order to increase her ransom payment. The film is a reimagining of the 1980 John Cassavetes film Gloria. This has apparently made some people angry. These people have apparently forgotten that Cassavetes never really wanted to make Gloria, and that, while remakes are rarely good things, a very, very loose remake of one of his studio films is not the same as remaking The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. Anyway, whereas Gloria was an amusing pastiche of seventies revenge and exploitation films, replacing Clint Eastwood or Charles Bronson with a middle-aged Gena Rowlands, Julia is a far more serious and dramatic work. In fact, one could almost say it is too serious and too dramatic.

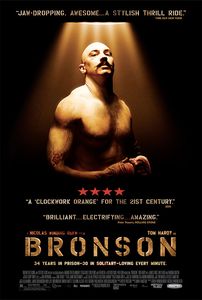

Erick Zonca’s Julia is a rare type of film, one that works largely in spite of its own script. Yes, it is twenty minutes too long, needlessly convoluted and it ends poorly, but through a combination of fantastic acting and some beautiful photography, it somehow finds a way to succeed. The film starts Tilda Swinton as a desperate southern California alcoholic who finds herself wrapped in a plot to kidnap the long-lost son of a casual acquaintance from his wealthy grandfather, but soon takes matters into her own hands in order to increase her ransom payment. The film is a reimagining of the 1980 John Cassavetes film Gloria. This has apparently made some people angry. These people have apparently forgotten that Cassavetes never really wanted to make Gloria, and that, while remakes are rarely good things, a very, very loose remake of one of his studio films is not the same as remaking The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. Anyway, whereas Gloria was an amusing pastiche of seventies revenge and exploitation films, replacing Clint Eastwood or Charles Bronson with a middle-aged Gena Rowlands, Julia is a far more serious and dramatic work. In fact, one could almost say it is too serious and too dramatic. I love Death Wish. It’s an all out crazy movie that is reined in just enough so that it doesn’t become complete parody, unlike its infinite iterations. Charles Bronson, the main star of that movie, is sort of crazy in a Wesley Snipes kind of way, except without the whole tax fraud thing. Bronson became the go-to guy when you needed an actor to kick a whole lot of ass throughout the 70s. He always did it with flair and Bronson’s craziness was always complemented by that element of “badassery.”

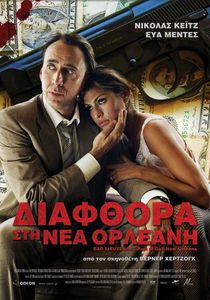

I love Death Wish. It’s an all out crazy movie that is reined in just enough so that it doesn’t become complete parody, unlike its infinite iterations. Charles Bronson, the main star of that movie, is sort of crazy in a Wesley Snipes kind of way, except without the whole tax fraud thing. Bronson became the go-to guy when you needed an actor to kick a whole lot of ass throughout the 70s. He always did it with flair and Bronson’s craziness was always complemented by that element of “badassery.” At this point, Werner Herzog stands in rarefied air, in the mix for every discussion of the “greatest living filmmaker,” and almost unquestionably the most influential living European filmmaker after some of the surviving members of the Nouvelle Vague, which made the announcement that he would be directing Nicolas Cage in a sort of-remake of Abel Ferrara’s 1992 Bad Lieutenant even more perplexing. Thankfully, he is still Werner Herzog, and not only has he vastly improved on the original, but Bad Lieutenant: Port Of Call New Orleans is his greatest narrative film since Nosferatu in 1978 (and yes, I know that means I’m saying it’s better than Fitzcarraldo). This is a stunning, beautiful and darkly comedic look at post-Katrina New Orleans anchored by Nicolas Cage’s best performance in years. It’s also Herzog’s strangest film since Even Dwarfs Started Small, although that seems likely to change soon, with the David Lynch-produced(!) My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done already opening in New York and LA later this month.

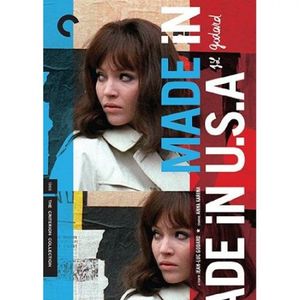

At this point, Werner Herzog stands in rarefied air, in the mix for every discussion of the “greatest living filmmaker,” and almost unquestionably the most influential living European filmmaker after some of the surviving members of the Nouvelle Vague, which made the announcement that he would be directing Nicolas Cage in a sort of-remake of Abel Ferrara’s 1992 Bad Lieutenant even more perplexing. Thankfully, he is still Werner Herzog, and not only has he vastly improved on the original, but Bad Lieutenant: Port Of Call New Orleans is his greatest narrative film since Nosferatu in 1978 (and yes, I know that means I’m saying it’s better than Fitzcarraldo). This is a stunning, beautiful and darkly comedic look at post-Katrina New Orleans anchored by Nicolas Cage’s best performance in years. It’s also Herzog’s strangest film since Even Dwarfs Started Small, although that seems likely to change soon, with the David Lynch-produced(!) My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done already opening in New York and LA later this month. If there were one film director most analogous to Bob Dylan it would probably be Jean-Luc Godard. Both released an astounding amount of brilliant, medium changing content representative of sixties culture (Godard 18 films, Dylan 9 albums) only to completely shift gears in the 1970s. While Dylan zoned in on the personal and started to sing about family life and how great it was to catch rainbow trout, Godard began branching out into the cold world of politics.

If there were one film director most analogous to Bob Dylan it would probably be Jean-Luc Godard. Both released an astounding amount of brilliant, medium changing content representative of sixties culture (Godard 18 films, Dylan 9 albums) only to completely shift gears in the 1970s. While Dylan zoned in on the personal and started to sing about family life and how great it was to catch rainbow trout, Godard began branching out into the cold world of politics. Café and Cabaret: Toulouse-Lautrec’s Paris

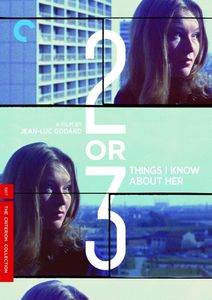

Café and Cabaret: Toulouse-Lautrec’s Paris Who is she? Who is “Her?” This is the first question that is inevitably asked of Jean-Luc Godard as the title cards repeat the nationally colored words: 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her.

Who is she? Who is “Her?” This is the first question that is inevitably asked of Jean-Luc Godard as the title cards repeat the nationally colored words: 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her.