Robert Warshow said, “A man goes to the movies. The critic has to be honest enough to admit that he is that man.” As a man who is not really even a critic, I present my ten favorite movies of the decade. These are not the ten “best.” I possess neither the experience, the expertise nor the cajones to claim to know such information.

10. Memento

It was the gimmick of the year: Take the story of a man with no short-term memory and tell it backwards, so that the audience has no short-term memory, either. The idea was tricky and ingenious, and could have failed spectacularly in any number of ways, not least by being confusing as all heck. Although Roger Ebert argued in his 2001 review that “confusion is the state we are intended to be in,” Memento is actually quite simple to understand after the fact, once we can fit all the pieces together in our minds. Before and during the fact, however, Memento is indeed a challenging experience, even on subsequent viewings, when we are somehow thrown back to square one and made to forget what eventually happens (or rather, has already happened) to the movie’s hero, Leonard Shelby, played by Guy Pearce. Directed by Christopher Nolan, the movie is about Leonard’s journey to avenge his wife’s murder—the assailant’s attack also caused Leonard’s “condition”—and its many twists raise provocative questions about the nature of memory, trust, friendship and happiness. I like a movie that considers the Big Questions and also manages to be inherently fascinating and intellectually stimulating. Memento is that movie.

9. The Dark Knight

The superhero movie was not invented in the last decade, but in recent years we have seen this once-campy action subgenre evolve into something almost respectable. Not only has the quality of movies based on comic books, or “graphic novels,” dramatically increased—with exceptions—but so has their reach. For every Spider-Man and Ironman there was also Ghost World and American Splendor—stories about ordinary people with ordinary problems that were nevertheless adapted from the pages of comic books. Yet the best of the best—the movie that brought together action, humor and tragedy into a remarkably engrossing whole—was Christopher Nolan’s Batman sequel, in many ways the most traditional of the superhero sagas. The casting proved superlative—from the brooding and charismatic Christian Bale and Aaron Eckhart to the dignified and God-like Michael Caine and Morgan Freeman—capped by the mad stroke of genius in the form of the Joker, played by Heath Ledger. The question that will never be answered is whether the movie would have been so mesmerizing had Ledger not died six months prior to the film’s première, sparking the perfect storm of anticipation and morbid fascination that helped the film become the biggest moneymaker of the decade. When I queried Globe critic Ty Burr in an online chat, he was as mystified as I was.

8. Kill Bill

Because Quentin Tarantino’s four-hour revenge epic is presented as two “volumes”—the first is more Eastern while the second is more Western—the story goes that your personality type can be explained by which volume you like the most. At the moment, I split the difference by liking Vol. 2 more but admiring the first volume’s “Showdown at House of Blue Leaves” more than any sequence in the whole set. In any event, I love Kill Bill as a whole and could watch it from any given point onward. The saga’s supreme feat of cleverness comes from splitting it in half: As advertised, Vol. 1 is pure kung-fu action of a profoundly shallow nature. Because it provides hardly any back story about the Bride (Uma Thurman) and because Bill himself (David Carradine) hardly appears at all, Vol. 1 is essentially a well-made, gory guilty pleasure. Vol. 2, then, sneaks up on us by developing not only the story but also the characters, including the relationship—rudely interrupted by the wedding chapel massacre that got the whole thing started—between the Bride and Bill, which is further complicated by an 11th hour revelation that leaves the Bride thunderstruck. Kill Bill might also represent a kind of weird flowering of contemporary feminism, since most of the major characters (and all the ones who survive) are strong, independent women. Admittedly, when I ran this theory past my mother, she wasn’t the least bit more inclined to see the damn thing.

7. Spirited Away

Hayao Miyazaki is the most valuable Japanese import to America since the Toyota Corolla. His hand-drawn animated films have seen only modest success in the United States, but around the world and within the film industry he is considered a deity. The reputation is well-deserved. While Pixar has churned out one computer-generated money-maker after another—clever and entertaining, one and all—Miyazaki has spent the last quarter-century producing full-length cartoons that are both high entertainment and high art. Some recent high points have included Princess Mononoke and Howl's Moving Castle, but 2002’s Spirited Away is in a class by itself. It’s as wondrous and inventive as any animated film I’ve seen, and deserves comparison with Disney’s golden age—appropriately, Disney has been Miyazaki’s distributor here in the States. Spirited Away is essentially a more solemn and mature retelling of "Alice in Wonderland," following a 10-year-old girl named Chihiro as she stumbles upon a bathhouse inhabited by creatures of the spirit world, necessarily drifting away from the world of her parents. The movie considers the importance of individualism, courage and determination in its young heroine, who proves herself worthy of the challenge. She is granted many guardian angels along the way, but the ultimate mission of returning home is left up to her. Spirited Away is about a child, but it’s not a “children’s movie” any more than New Moon is a movie for vampires.

6. Almost Famous

Cameron Crowe’s quasi-autobiographical tale of growing up as a teenaged Rolling Stone reporter during the “death rattle” of rock ‘n’ roll is a pleasure to behold. Not only is Almost Famous one of the great movies about the 1970s American music scene, but it’s also one of the great movies about journalism. I must admit that two big reasons I so love Almost Famous are, first, its glorious soundtrack—featuring The Who, Led Zeppelin, Elton John, The Beach Boys and Simon and Garfunkel, to name a few—and second, its protagonist, William Miller (Patrick Fugit), in whom I undoubtedly saw bits of myself as I was preparing to shove off for college in the hopes of becoming a writer. The movie does not exactly romanticize the writing profession, since William spends most of his time failing to get his subjects to talk to him. But the band he follows—a struggling, fictional outfit named Stillwater—provides him an enlightening and entertaining exposure to sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll, as does the band’s groupie-in-chief, Penny Lane (Kate Hudson), who becomes his unofficial guide through the haze of ego, ambition and bullshit that is the American music industry. Two other reasons to see it: Frances McDormand as William’s irrepressible mother, and Philip Seymour Hoffman as the rock critic Lester Bangs, who knows a good writer when he sees one.

5. No Country for Old Men

How ironic that when the Oscar for Best Picture was finally bestowed on Joel and Ethan Coen—two of the most visionary minds in cinema—it would be for an adaptation. Just as it seemed odd for Martin Scorsese, an Italian from Manhattan, to be showered with the ultimate praise for an Irish movie set in Boston, it didn’t feel quite right that the creators of Fargo and The Big Lebowski should be similarly honored for a story that was not their own. And yet No Country for Old Men is a considerable achievement in its own right—a cat-and-mouse game between a relentless killing machine and a crafty but blundering welder who gets in way over his head. The villain, Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), is the latest movie bad guy who seems to be on screen more than he actually is; his menacing presence haunts every scene. Last summer I wrote a 3,500 word essay about Chigurh’s pathology (for academic purposes), and I can’t say I’m any closer to understanding what makes him tick. Other stars of the film are the camerawork and the sound mixing, which give the movie an urgency and a crispness that mesh so well with the story and characters. The ending infuriated a lot of people, but I thought it was absolutely on-target in reflecting what the movie was really about.

4. City of God

Oddly enough, there is no movie on my list directed by Martin Scorsese. This is notable, first, because he is probably the best living filmmaker in America (if not the world) and second, because this ends his streak of making arguably the best movie of three decades in a row: Taxi Driver in the 1970s, Raging Bull in the 1980s and GoodFellas in the 1990s. He made several good movies in the 2000s, but none were of the same caliber as those timeless and visionary works.

Although Scorsese himself is not represented here, my top ten is not without a movie in the classic Scorsese mold—namely, a movie with passion and excitement, teeming with life but also the constant threat of violence and death, following the lives of characters who inhabit a world on the fringes of civilized society and have to deal with the realities of that existence. In this decade, City of God, directed by Fernando Meirelles and Katia Lund, filled the void.

Like GoodFellas, City of God follows many years in the fortunes of its protagonist and the assorted lowlifes he encounters. His name is Rocket, and he lives in the lawless slums of Rio de Janeiro that are run by armed gangs of teenagers whose leaders typically live halfway into their 20s before being killed off and replaced, often by their own deputies. The movie is an expose of sorts, and a demonstration—especially in the climactic gang war—that this cycle of violence will continue forever until outside forces intervene. If the cops in this movie are any indication, such a solution is easier said than done.

In early 2003, City of God was the subject of one of the most shameful moments in Oscar history, when the Academy failed to nominate the movie in the foreign film category after 60 people reportedly walked out of the official screening for Academy voters. The incident was a scandal that, to its credit, the Academy rectified the following year by nominating the movie in four categories: Direction, editing, cinematography and screenplay. The movie has gained traction in the public eye ever since, and is currently ranked No. 16 on the Internet Movie Database poll of the all-time best films.

3. Minority Report

Steven Spielberg is the most successful film director in the history of the medium, and so we sometimes forget how good many of his movies are. In the first decade of the new century he was as productive as he’s ever been, directing seven features and producing more than a dozen more. Granted, some of these were throwbacks (Indiana Jones 4, War of the Worlds) and others were good but forgettable (Catch Me if You Can, The Terminal). On the other hand, Munich was a serious and chilling piece of dramatic history and A.I.: Artificial Intelligence was a project of extraordinary ambition and audacity that A.O. Scott was compelled to call “the best fairy tale Mr. Spielberg has made.”

For me, the best of the best in the recent Spielberg canon—as emotionally sober as Munich and as visionary as A.I.—was Minority Report. All but forgotten by a sizable cross-section of 21st century moviegoers, Spielberg’s 2002’s sci-fi thriller was his most artistically successful film of the decade because it combined all the elements that comprise his best work: Dazzling special effects, a compelling story with memorable characters, told in a physical and moral environment that is recognizable but also wholly unique in the world of film.

The plot of Minority Report is not only compelling but also highly political without stepping into outright preachiness. The situation: In Washington, D.C., in 2054, a successful law enforcement program called “Pre-crime” is preparing to expand across America. The program works thanks to three human oracles, or “pre-cogs,” who can predict violent crimes in near-perfect detail, allowing the cops to “catch” the offenders before the crimes actually occur. The trouble starts when the chief officer, played by Tom Cruise, is accused of being a future criminal himself—destined, according to the pre-cogs, to murder someone he doesn’t know in less than 36 hours.

The ensuing chase is superbly entertaining and entirely logical. The same can be said of the film as a whole. The story contains very little of the usual Spielberg manipulation that, for example, prevented A.I. from being a true masterwork. At the same time, Minority Report contains twists so clever that I was delighted by them on my first viewing and have appreciated their ingenuity ever since. Critics of the film have faulted the third act for being too soft, but I think it succeeds in reinforcing the human element of the story, which gives the movie its moral center.

2. Adaptation

The first question you ask when a friend recommends a movie is, “What’s it about?” I don’t think I have ever had a more difficult time answering that question than in conversations about Adaptation, made in 2002 by Spike Jonze.

Adaptation is about flowers. About their allure to greedy Florida poachers and their Native American friends who’re allowed to steal them from state-owned lands with impunity. About the obsession of one such poacher, John Laroach, who makes a living from flowers but seems to switch lifestyles every few years, as though obsession itself is his only real calling.

Adaptation is about screenwriting and the enormous difficulty it takes Charlie Kaufman to turn The Orchid Thief, a book about Laroach, into a film script. About Kaufman’s insecurities and self-doubt about his writing abilities, even after penning a big hit. About his self-loathing and sweating and need to impress the right people and get the girl.

Adaptation is about Darwinism, and the ways different flowers seem to be designed to attract different bees into the act of pollination, which is all that keeps the world from falling into darkness. About the need for passion—to be driven by a desire for knowledge, wisdom and transcendence.

Most of all, Adaptation is about the process by which Charlie Kaufman utterly failed to adapt The Orchid Thief into a movie and, in the midst of his failure, ended up with one of the great original screenplays of modern movies.

Adaptation was the first R-rated movie I saw theatrically. The initial experience blew me away to the point of utter mystification. In the intervening years I have watched it as much as any movie of its kind and I never tire of it because it is so damned complicated. I would call the experience “rewarding” if that weren’t such a facile word. “Exhausting” is probably more accurate, but I know that won’t gain many converts, either. Adaptation boasts some of the best names in the business—namely Meryl Streep, Nicolas Cage and Chris Cooper—but it is very much a niche movie for a small audience.

What I know for sure is the brilliance of the screenplay, which operates on at least three levels of reality at once but contains no tricks of logic or continuity. Again, this was a movie whose ending upset a lot of people—mostly critics, in this case—who thought it concluded on a cheap note. In fact, given the movie up until its final twist, no ending would have possibly made sense except the one we have. That Charlie Kaufman is one smart cookie.

1. Lost in Translation

I must admit that I am often a man of contradictions. I just finished explaining that I adore Adaptation for its unparalleled complexity and I am now concluding my list with a film that is a study in unadulterated simplicity.

The story: Bob Harris (Bill Murray) is a fading, tired movie star who is shooting a whiskey commercial in Tokyo. During his first night in the hotel bar he meets Charlotte (Scarlet Johansson), a young American college graduate who is in Tokyo with her photographer husband. Bob has been married for 25 years, Charlotte for two. Over the next few days they follow each other around, check out the fabulous Tokyo nightlife together and engage in idle but thoughtful conversation about the meaning of their lives and marriages.

That’s it. That’s the whole movie. Indeed, with a premise like that, the miracle is that the damned thing got made at all. Lost in Translation was written and directed by Sofia Coppola, who had only made one movie before this one but had the obvious genetic advantage of being Francis Ford Coppola’s daughter. Nepotism is alive and well in Hollywood, but rarely does it result in a movie this remarkable.

It’s one thing to tell a story. To encapsulate a feeling, or a mood, is infinitely more difficult. Lost in Translation is about its characters—about their melancholy, their yearning, their ambivalence about the decisions they’ve made, their happiness and the ordinary ways they express these feelings. It has always been true that the best way to express universal truths is to be as specific as possible. Because this movie is so intensely about Bob and Charlotte—and about nothing else at all—it becomes a movie about everyone and everything.

One of my more literate friends once complained about the teaching of Shakespeare in high school, saying, “Shakespeare cannot be analyzed—he can only be appreciated.” That is what Lost in Translation means to me. Coppola’s film is not above criticism, it’s not perfect and it’s not Shakespeare. But it affected me in a way that makes any analytical statement beside the point. Like the Disney animated classics that made up the formative years of my childhood, I regard this film as a fact of life—as though it happened to me—and not really as a movie at all.

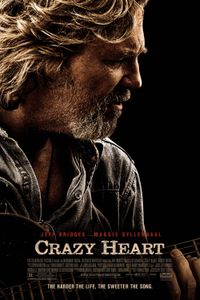

Crazy Heart, directed by Scott Cooper, and adapted from the novel by Thomas Cobb follows a pretty stereotypical plot. Jeff Bridges stars as country music singer Bad Blake, a performer who has seen better days. He is overweight, always drunk, and looks like he could use a good shower with a shave. Bad travels the country, performing his old tunes in bowling alleys and bars. He sleeps in motels that don’t look a whole lot better than the cab of his truck, and argues with his manager about future gigs. All in all, there is not a whole lot going for him but his past because he refuses to work on new material.

Crazy Heart, directed by Scott Cooper, and adapted from the novel by Thomas Cobb follows a pretty stereotypical plot. Jeff Bridges stars as country music singer Bad Blake, a performer who has seen better days. He is overweight, always drunk, and looks like he could use a good shower with a shave. Bad travels the country, performing his old tunes in bowling alleys and bars. He sleeps in motels that don’t look a whole lot better than the cab of his truck, and argues with his manager about future gigs. All in all, there is not a whole lot going for him but his past because he refuses to work on new material.

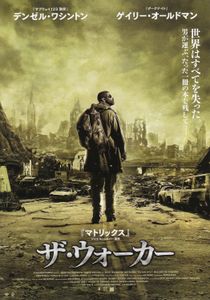

I’m no sociologist, but it would appear that the current socio-economic climate has finally caught up with Hollywood, and they have reacted pretty much as expected: with lots of explosions. The apocalypse has become a major feature in American film, spurred by a fear of the coming end of our time as the dominant country, the collapse of the economy and the imminent ruin of our environment. Whether the apocalypse is caused by the Earth itself (2012), the same vampires who have invaded our pop-culture (last week’s Daybreakers), angels from above (next week’s Legion), causes unknown (The Road) or good old fashioned nuclear war, like this week’s Book Of Eli, humanity’s struggle to survive in the face of doom has become fashionable again despite a brief post-9/11 dip in which it may have been considered tasteless by some. I think this sub-genre can lead to great art in most forms (I haven’t seen the film version of The Road, but the book won the Pulitzer for a reason), but, in film, more often than not, it leads to silly Mad Max rip-offs, as is the case with The Book Of Eli. You should never expect much out of a January action picture, and I’ve certainly seen worse over the years, but The Book Of Eli is just so over-stylized, so self important and so embarrassing for the pretty good actors involved that it crosses the level of normal bad film to pure unintentional hilarity.

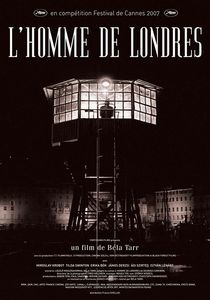

I’m no sociologist, but it would appear that the current socio-economic climate has finally caught up with Hollywood, and they have reacted pretty much as expected: with lots of explosions. The apocalypse has become a major feature in American film, spurred by a fear of the coming end of our time as the dominant country, the collapse of the economy and the imminent ruin of our environment. Whether the apocalypse is caused by the Earth itself (2012), the same vampires who have invaded our pop-culture (last week’s Daybreakers), angels from above (next week’s Legion), causes unknown (The Road) or good old fashioned nuclear war, like this week’s Book Of Eli, humanity’s struggle to survive in the face of doom has become fashionable again despite a brief post-9/11 dip in which it may have been considered tasteless by some. I think this sub-genre can lead to great art in most forms (I haven’t seen the film version of The Road, but the book won the Pulitzer for a reason), but, in film, more often than not, it leads to silly Mad Max rip-offs, as is the case with The Book Of Eli. You should never expect much out of a January action picture, and I’ve certainly seen worse over the years, but The Book Of Eli is just so over-stylized, so self important and so embarrassing for the pretty good actors involved that it crosses the level of normal bad film to pure unintentional hilarity. Bela Tarr is my favorite filmmaker, and The Man From London, coming soon to the MFA, is only his third film in the last twenty years. The last two, 1994’s Satantango and 2000’s The Werckmeister Harmonies are my favorite films of their respective decades, and the later is also simply my favorite film. Unless some kind soul decides to do a much-needed retrospective of his work, this will, in all likelihood be the only review of one of his films I write for this site. He has another film in production at the moment called The Turin Horse, but considering the fact that this is the Boston premier of The Man From London, nearly three years after its Hungarian premier, I’m not sure when we’ll actually see it. He’s claimed that The Turin Horse, which is rumored to be in consideration for Cannes this year, will be his last film. If this is true, then to simply call it a tragic loss for cinema would not be enough. The comparison has probably been made enough, but Tarr is the Andrei Tarkovsky of his generation. Not so much in an ideological sense, or even an aesthetic one, beyond their shared affinity for slower, more contemplative cinema, but in their greater shared mastery of cinema as an art. If that comparison must go on, then this is Tarr’s Nostalghia or his Sacrifice. For the first time in his career, Tarr’s film is not explicitly set in his native Hungary and does not concern itself with the problems of that nation, but rather society as a whole. Of course, rather than Tarkovsky’s forced exile, this was a choice afforded to him by the greater success of his last two films. This is the natural progression of his work, and while the film may not achieve the beautiful perfection of his last two, it is still a great film and a vital work in understanding the art of one of film’s greatest minds.

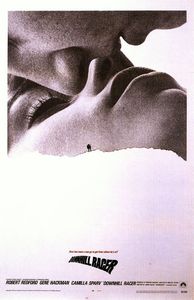

Bela Tarr is my favorite filmmaker, and The Man From London, coming soon to the MFA, is only his third film in the last twenty years. The last two, 1994’s Satantango and 2000’s The Werckmeister Harmonies are my favorite films of their respective decades, and the later is also simply my favorite film. Unless some kind soul decides to do a much-needed retrospective of his work, this will, in all likelihood be the only review of one of his films I write for this site. He has another film in production at the moment called The Turin Horse, but considering the fact that this is the Boston premier of The Man From London, nearly three years after its Hungarian premier, I’m not sure when we’ll actually see it. He’s claimed that The Turin Horse, which is rumored to be in consideration for Cannes this year, will be his last film. If this is true, then to simply call it a tragic loss for cinema would not be enough. The comparison has probably been made enough, but Tarr is the Andrei Tarkovsky of his generation. Not so much in an ideological sense, or even an aesthetic one, beyond their shared affinity for slower, more contemplative cinema, but in their greater shared mastery of cinema as an art. If that comparison must go on, then this is Tarr’s Nostalghia or his Sacrifice. For the first time in his career, Tarr’s film is not explicitly set in his native Hungary and does not concern itself with the problems of that nation, but rather society as a whole. Of course, rather than Tarkovsky’s forced exile, this was a choice afforded to him by the greater success of his last two films. This is the natural progression of his work, and while the film may not achieve the beautiful perfection of his last two, it is still a great film and a vital work in understanding the art of one of film’s greatest minds. When I saw that Criterion was releasing Downhill Racer I was surprised to say the least. I knew little about the film, but I did know it starred Robert Redford and that it was about skiing. Hollywood stars and sports did not seem in line with Criterion’s general release of foreign flicks, lost classics from the first half of the century, and art-house films. More than anything I was confused. That surprise and shock however slowly evolved into delight watching this minor masterpiece unfold.

When I saw that Criterion was releasing Downhill Racer I was surprised to say the least. I knew little about the film, but I did know it starred Robert Redford and that it was about skiing. Hollywood stars and sports did not seem in line with Criterion’s general release of foreign flicks, lost classics from the first half of the century, and art-house films. More than anything I was confused. That surprise and shock however slowly evolved into delight watching this minor masterpiece unfold.