Prompted by Dean Sapiro’s lecture on Mary Wollstonecraft to question why there are so few women authors in the Core Humanities, Prof. David Green had his CC 202 students this week momentarily put aside Pride and Prejudice and the question of whether happiness in marriage is a matter of chance to consider the criteria for including authors in our curriculum. In the following guest post, Prof. Green reports on the results of those conversations, and gives his own reflections on the matter of Core and the canon.

Most of the students I have had in my classes over the last fifteen years have been women. Before enrolling in the program, most, if not all, are familiar with the list of authors that includes Homer, Aristotle, Virgil, Dante, Shakespeare, Cervantes, Milton, and Dostoevsky. They choose to study these authors for a variety of reasons, but that doesn’t mean they don’t wonder about the dearth of women authors. And when we finally reach March of the second year and begin reading Wollstonecraft, Austen, and Dickinson, there is often a sense of “well, about time.”

In my Wednesday classes last week we began by asking, “What is the purpose of the program?” In other words, “why do we read these authors?” The answer was almost always, “To provide a foundation,” or more specifically, “an intellectual foundation of our civilization.” Upper level courses can build on that foundation and explore various developments in the history of ideas by focusing more narrowly on specific periods or genres or themes. For example, if a student studies deconstruction as a senior, it is essential to have some knowledge of Platonic metaphysics. If one studies Fielding’s novel Joseph Andrews as a junior, it is helpful to know Don Quixote. If one studies contemporary art theory, it is important to know the contributions of Velazquez and Rembrandt.

While the Core reading list is canonical, there is no such thing as a fixed and comprehensive Canon. Contrary to a popular misconception, the list we use is regularly subject to modification. Every year the Core faculty discusses possible changes not only to the reading list, but also to the list of artists and musicians, and more often than not, depending on the course, one or two works will be added or taken out. So students are often surprised to learn that their predecessors read Job, Aeschylus, or Kant’s Groundwork, but may not have read Dostoevsky or Voltaire. Before I started teaching in the second year, students read Christine de Pizan, and in recent years, I have taught the following authors who are no longer on the list: Chaucer, Rabelais, Donne, Emerson, Thoreau, and Chekov. We also studied Goya and van Gogh in the past.

In this constant process of reassessing the curriculum, we are accustomed to asking ourselves why one text should be included and not another. And we are acutely aware of the arguments that we should include more women and minorities. If the humanities component is canonical by design, then our criteria for inclusion must be consistent with the nature and purpose of the canon. So what is a canon? Originally the term was used to designate the books that would be included in the Bible. Those left out were called the apocrypha. So from its inception, the idea of a list has been exclusive as well as inclusive. Historically the western canon has been determined by editors, social commentators, scholars, critics, established authors themselves, and the public. The people who participated in these discussions were usually white males in Europe. And though the words “white males” can immediately rouse suspicions of bias, it’s only natural that those who participated were also those who were more highly educated and had leisure to devote to books and ideas.

That is no longer the case, and so the canon being established today, if the list of Nobel Prize winners is any indication of longevity, may include Pablo Neruda, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Wole Soyinka, Octavio Paz, Nadine Gordimer, Derek Walcott, Toni Morrison, Kenzaburo Oe, V.S. Naipul, Gao Xingjian, and Doris Lessing. Still not representative of the world population, but a better representation than in the past. Does the fact that more minorities and women are being recognized for their writing today mean that more minorities and women should now be included in the historical canon? After all, even the Constitution of the United States is subject to change by amendment. Or does the canon have a validity of its own, for better or worse, as a loosely constructed historical artifact that may be used to discuss not only what was included in the past, but also what was excluded, and why?

When my classes discussed the criteria for inclusion, two stood out in particular. First of all, our reading should include works that were critically influential and helped to determine our intellectual history. For example, our current form of government was established by Enlightenment figures who read not only Machiavelli, Shakespeare, Locke, Hobbes, Swift, Voltaire, Rousseau, and Kant, but also Plato and Aristotle. The second criterion mentioned was that these works should conform to the highest quality of artistic achievement and intellectual value. In other words, as one student said, to be included, a work must be “as good as” the others. But another student immediately pointed out that any sense of value has been culturally determined by a select minority of people. Both comments are persuasive.

So I asked my classes what it means to be “as good as”? I told them that many years ago I was interested in a popular writer who is often included in the canon of modern American Literature. I opened up one of her books at random and read that a child had eyes the color of caterpillars. I put the book down and never picked up another by this author. Caterpillars come in variety of colors and so the description was vague to the point of being meaningless. The writer had not achieved a high level of artistic quality. At the time I read this passage, I was teaching in a Catholic high school for young women and asked my students if they liked this author and one said she did because the author described a family where all the sisters had different hair, and, the student explained, in her family all her sisters had different hair. The most important criterion for this student when appreciating a work of literature was whether she could identify with it or not.

Has identification become the principal criterion for deciding whether a work belongs in the current or even historical canon? Does a student need to find authors similar to him or herself in gender and race in order to feel the readings are valuable? As a white man, I may not be the best person to answer this question because most works we read were written by white men. But I will say that in general I can identify with texts that were written by women and minorities—unless those texts were specifically about experiences that only women and minorities have. And even if I can’t identify with a work that doesn’t address universal human concerns, I can still learn to understand and empathize with lives that are unlike my own. In this way such a text is valuable.

Are the works written by men in the Core about experiences that only men can have? Are they about what it means to be a man? Or are they works that deal with universal human concerns? Just because a work does not address experiences specific to being a women, does that also mean it doesn’t address the experiences of women as human beings? Do women develop ethical characters by employing Aristotelian practical wisdom? Are women subject to the allegorical leopard, lion, and wolf of Dante’s Divine Comedy? Can women feel the same way Don Quixote feels about Dulcinea when he says, “And to put it in a nutshell, I imagine that everything I say is precisely as I say it is, and I depict her in my imagination as I wish her to be, both in beauty and in rank.”

Two related questions that may be worth asking here are whether only women can write authentically about the perspectives and experiences of women and whether only men can write about the perspectives and experiences of men. Is Jane Austen’s depiction of Mr. Darcy inauthentic? Is Goethe’s depiction of the plight of unmarried mothers in the eighteen century? Many of the most memorable depictions of women have been conceived by men from Chaucer’s Wife of Bath to Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth to Ibsen’s Nora Helmer to Joyce’s Molly Bloom, to Fugard’s Miss Helen. And many of the most memorable depictions of men, like Mr. Rochester, Heathcliff, and Flannery O’Connor’s Haze Motes have been created by women. Are they inauthentic?

Because many of the authors we read were writing about a time before women received formal educations, they did not include women directly in their discussions. For example, when writing on “Of the Education of Children,” Montaigne is addressing a noblewoman and assumes that her unborn child is a boy (because, he says, “you are too noble-spirited to begin otherwise than with a male”) , and then goes on to write about boys, but when I read works like this, I often include the feminine pronoun or ask, is this also the case for women? I do this when reading Montaigne because most of what he goes on to say on the subject of education applies equally to women and men. At the same time, we may take a moment to reflect on the kinds of prejudices that existed toward women historically—evidenced by the parenthetical remarks.

As things stand now, when we consider works for possible inclusion in the Core reading list, we primarily focus on the degree to which those works have influenced subsequent thought, provide insight into the human condition, contain profound ideas, and achieve a high level of artistic merit. Of course the fact that these criteria are, as my student pointed out, culturally determined makes any deliberation using them open to question. Are there works that were not influential because of cultural ignorance or indifference that deserve to be included because they represent important social, philosophical, or artistic developments that we have failed to consider?

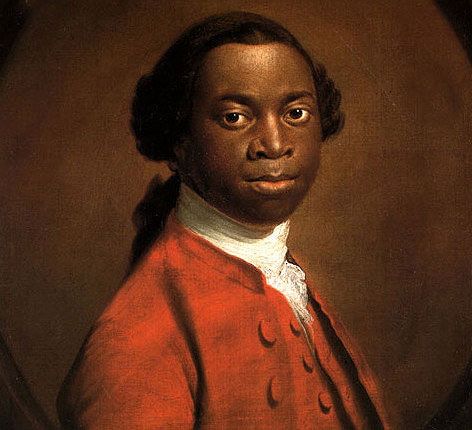

Three works that were suggested for inclusion in either the lecture, my class, or the Core office were Olaudah Equiano’s The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko, and Juana Inés de la Cruz’s “First Dream.” I haven’t read any of these works and so at present can’t evaluate them using three of the criteria mentioned above. But it is fair to ask whether the experience of a twenty-eight year old Englishman reflecting on time past while looking over the Wye valley is more culturally significant than the experiences of an African slave who bought his freedom. Was Equiano’s work only excluded from the historical canon because he was black or because his experience was unflattering to those who determined the canon? If so, then his work deserves to be considered. Behn’s work is already in the canon in the sense that it appears in the Norton Anthology of English Literature, and therefore satisfies the criteria for artistic merit and cultural significance. Juana Inés de la Cruz’s work, the subject of an important study by Octavio Paz, is more widely known in the Spanish-speaking world than in the English. If a good literary translation is available, her work might also meet the most important criteria for inclusion.

The next question is which works would we take out of the program? When I began teaching in Core almost fifteen years ago, we read more books and overall number pages in the humanities courses than we do now and it’s unlikely we would want to increase that number, so something would have to go. To use the words of my student, are the works of Equiano, Behn, and Sor Juana “as good as” the works of Goethe, Rousseau, Austen, Dostoevsky, and Nietzsche? Another criterion that has not been discussed yet is whether these works fit in to the thematic arcs that span the courses and semesters. Since many of the works we study exist in conversations with each other, we might lose that facet of the course if a work exists outside that conversation.

It is another misconception to think that because we teach canonical works we are not interested in works that lie outside the canon. In fact, I think we all encourage our students to pursue their interests in women’s studies, or world literature, or minority literature in their other courses. We see our role not in some kind of political opposition to these more specific areas of study, but as providing a strong foundation upon which these later courses can build. Also, given the tightness of the humanities syllabus as it stands, works dealing more directly with issues of social injustice might be covered more effectively in the Social Science courses, which can provide a more comprehensive conversation on that subject. Eventually we may be able to add a third year of Core Humanities and we would certainly have Virginia Woolf on the list of canonical twentieth century authors. Marcel Proust and Richard Wright might add to the diversity of that course.

A canonical reading list should not be regarded with suspicion as an attempt to diminish the value of works that it doesn’t include. It is the result of a great deal of deliberation and even sacrifice on the part of the faculty. We understand better than anyone what it is like not to have a work we value on the list, and if we were allowed to write our own lists, they would be distinct from the one we use in common. A broader question is whether there is still a role for a course that teaches a collection of many of the most influential literary, philosophical, and artistic works of western and eastern civilization. I would argue that with more and more diversification of the subject matter in college courses, there is an even greater need for a program devoted to those works that helped to make us who we are.