March 12, 2017 at 12:32 am

“Anxiousness reminds us of existence; happiness momentarily forgets it existed.” The power of ‘it’ in that wonderful bit of existentialism comes in the ambiguity of its reference, and so reminding us of the closeness between ‘anxiety’ and ‘existence’, almost anagrams. One of the appeals of the existentialists, then, comes in their trying to work out the tension between these two; a tension which, unsolved, pulses with an anxiety of its own. Professor Shahidha Bari, writing for the TLS, recites some of the questions raised during a panel at the London School of Economics to open discussion about the ways in which these thinkers are not only relevant but needed. Serious problems sometimes ask for solutions that give us not only gravity but levity:

Its true that existentialism isn’t always easy, but it helps that many of the existentialists themselves were irresistible. As a young man, Sartre hurled water bombs from classroom windows, yelling Thus pissed Zarathustra! Simone de Beauvoir improvised elegant solutions to the straitened circumstances of life in Nazi-occupied Paris, wearing turbans when she could not secure a haircut, and sleeping in ski-wear to save on heating. Albert Camus, who was investigated by the FBI at the request of J. Edgar Hoover (the file was mislabelled Canus), could sit in the street in the snow, lamenting his love life, until two in the morning. He adored his cat, a creature blessed with the perfect moniker: Cigarette. Tell me whats not to love about these existentialists.

Professor Bari goes on to list many of the virtues of the philosophy and its thinkers. Besides charming anecdotes about Sartre’s scatological therapy for eschatological problems, Bari writes about the contentious friendship he shared with Camus, which persisted even when the latter ceased to exist.

Read her full post at The TLS

By Kush Ganatra

|

Posted in Great Ideas

|

Tagged albert camus, existentialism, sartre

|

March 10, 2017 at 11:30 am

Greetings, scholars! We hope spring break is treating you well. Here on the blog, we couldn't rest until we had compiled the choicest links for your perusal. Or something like that.

Wolfert at work on his one-man show. Via Sara Krulwich for the New York Times.

- The MFA is hosting a lecture at the end of this month called "The Benaki Museum and the Greek Narrative: The Role of Culture in Crisis." Lecturer Pavlos Geroulanos, former Minister of Culture and Tourism in Greece, will be focusing on the extensive collection of Greek art and artifacts located at the Benaki Museum and its connections to Greece's economic crisis.

- Seventeen years late, the movie The Man Who Killed Don Quixote is finally in the works, with Terry Gilliam of Monty Python fame at the helm.

- In other Don Quixote news, the 1910 opera Don Quichotte is being performed by the Island City Opera of Alameda, California through March 12. The opera is loosely adapted from the Cervantes text (as in, we've spotted DQ, Sancho Panza, and the windmill incident, but composer Jules Massenet has added something about a quest for a stolen necklace and now we're confused and flipping through multiple translations of Don Quixote for an explanation).

For the first Paris production in 1910. (Public Domain)

That's all for this week. We'll see you next week for more exciting adventures in the world of Core.

By cdossett

|

Posted in Uncategorized

|

Tagged weekly links

|

March 5, 2017 at 8:42 pm

It is one of the most valuable purposes of reading imaginative literature that it allows the reader to sympathize with the values of a culture different from his or her own. Having done so, memory, strengthened by the force of narrative, will also preserve those values. Peter E. Gordon therefore aptly begins his review of When Memory Comes, amemoir of historian of Nazism and the Second World War, Saul Friedlnder, by relating Canto 16 from Dante'sInferno,in which the pilgrim is beseeched by shades of the Florentine nobility to remember them once or if he makes it back up (as we know, he way overshoots the mark, landing in Paradise). For Professor Friedlnder (good name), though having managed with his family to escape Nazi persecution, nevertheless held powerfully in his conscience the tragedy which we are fortunate to learn about from the safe distance provided by the history books. Of the relationship between history and memory

Saul Friedlnder in Paris, 1978. (Ulf Andersen / Getty Images). Photograph for The Nation

Friedlnders two-volume Nazi Germany and the Jews suggests an answer to this question. Theorists of trauma have noted that first-person experience is often fractured, resistant to summary. Allowing such memories to punctuate a historical synthesis undoes the illusion of completeness; it reminds the reader that historical understanding is not just an obligation but a privilege. Historical scholarship occurs later, at a safe remove from the horrors it describes. In this crucial respect, the it was of history often differs from the I was of memory: The first integrates and promises comprehension; the second disintegrates and conveys incomprehension. The work of the historianand this is Friedlnders singular achievementis to unite these tasks so that the reader can understand, however imperfectly, experiences of trauma that would otherwise seem to surpass understanding.

The memoir closes the distance between reader and experience like the distant retelling of history cannot. Friedlander lost his parents in the camps; they succeeded in getting him to safety, and he succeeded in Proustian fashion to preserve their memory; but as his own memory fails, the least we can do is make it a part of our own by reading his memoir.

Read more at The Nation

By Kush Ganatra

|

Posted in Great Personalities

|

Tagged history, Holocaust, Memoir

|

March 3, 2017 at 11:30 am

Good afternoon, scholars! Before you shove off for spring break, we hope you'll take the time to read this week's links.

- The earliest-known image of Confucius was found in the tomb of the Marquis of Haihun, who briefly (and we mean brief--we're talking less than a month) reigned as emperor of China in 74 B.C. Discovered on the wooden cover of a bronze mirror, the philosopher's likeness is included alongside two of his students and 2,000 Chinese characters detailing stories not found in other Western Han Dynasty documents.

- Prof. Philippe Desan of the University of Chicago spills the goods on a certain French Renaissance philosopher and politician in his new biography Montaigne: A Life.

"Que sais-je?" Montaigne: A Life, by Philippe Desan. Translated by Steven Rendall and Lisa Neal. 2017.

- Harlem School of the Arts Theatre Alliance reshapes Euripedes' The Trojan Women to give it a contemporary flair. Set in a modern city, the play is directed by HSA Artistic Director Alfred Preisser, and it will take place from February 24 through March 19 at HSA Theatre in New York City.

- The Martha Graham Dance Company recently wrapped up their season at the Joyce Theater last Sunday, February 26, with performances working with the theme of Sacred/Profane. One program in particular, by Belgian choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, is inspired by Sufi mysticism and incorporates Middle Eastern music.

- The Boston Philharmonic's performance of Beethoven's Concerto for Violin, Cello, and Piano, receives a favorable review over at the Boston Globe. The Boston Trio (featuring Irina Muresanu on violin, Joan Ellsworth on Cello, and Heng-Jin Park on piano) played Beethoven's Triple Concerto and Bruckner's Symphony No. 9 last week at Sanders Theatre and Nec's Jordan Hall.

The trio. (Via Boston Philharmonic Orchestra.)

Well, that'll do it! We hope your break leaves you well-rested and ready for the remaining weeks of the semester.

By cdossett

|

Posted in Uncategorized

|

Tagged weekly links

|

February 26, 2017 at 9:39 pm

Eric Ormsby at Literary Reviewengages in his latest review with Christopher de Bellaigue'sThe Islamic Enlightenment. The relationship between the two has not been easy, but that it has been unrequited for either is a misimpression that has gained popularity in some circles, namely populist ones. That is too bad, because de Bellaigue argues that the Sunny side of the Islam has been getting brighter for the last two centuries (Shi'a right... Ormsby thinks):

De Bellaigues title turns on a paradox. We seldom, if ever, think of Islam, at least in its current form, as exemplifying, let alone promoting, enlightenment. Yet his intention is to demonstrate that non-Muslims and even some Muslims who urge an Enlightenment on Islam are opening the door on a horse that bolted long ago. He goes even further when he states that for the past two centuries Islam has been going through a pained yet exhilarating transformation a Reformation, an Enlightenment and an Industrial Revolution all at once. This seems to me somewhat overstated.

Through the course of this absorbing review Mr. Ormsbymanages to insert his opinions while also interesting the reader about what the book has to say. A question that proved especially difficult for the Muslim intellectual of the nineteenth century was that of the seeming inequity of divine dispensation: why do the spiritually awry get more of the share than Muslims? A question that provoked the Christians too centuries before, and still does today even if in a different from. If after this stage of puberty Islam will settle into the moderate mildness like Christianity before it, then there is certainly a Sunny side at least in the future.

Read his full post at Literary Review

By Kush Ganatra

|

Posted in Great Ideas

|

Tagged Enlightenment, Islam

|

February 25, 2017 at 11:08 pm

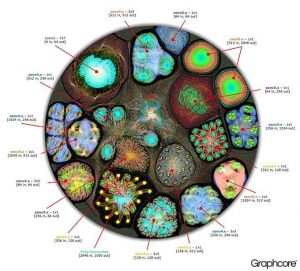

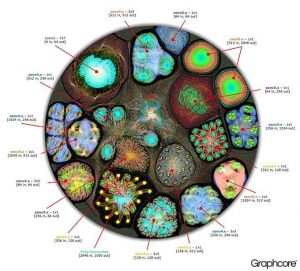

Graphcore is a start-up company that has recently secured $30m "to deliver massive acceleration for machine learning." One of its latest findings has been posted by Mark Frauenfelder at boingboing: "brain scans" of Graphcore's Intelligence Processing Unit (IPU), which is likea rudimentary brain that can performbasic processes related to learning and memory. Here's an image of its computational graph (used to help interpret information from data):

Image of Computational Graph for Graphcore

As for the most pressing concern: when will these things take us over? We do not know yet. But meanwhile we might spend our time pondering the kind of questions we've come to think ofas being typical at the Core, and perhaps even for the folks at Graphcore: the relation between appearance and reality. When that reality has to do with our perception of it, then introspection can only get us so far at a proper understanding. It reached its limits centuries ago, for the processes of the brain responsible for our sensation are not accessible to reflective analysis. We need the mediation of the kinds of instruments and machines that companies like Graphcore are working to develop. What's truly interesting is that-- *STATIC*... HELLO, MY NAME IS IPU:

READ HIS FULL POST AT boingboing

By Kush Ganatra

|

Posted in Great Photograph, Great Questions, In the News

|

Tagged appearance, artificial intelligence, Descartes, reality

|

February 24, 2017 at 11:30 am

Hello, Corelings! Enjoying the uncommonly good weather? We've compiled some equally good links for this week's round-up that might strike your fancy.

- Ipsa Dixit, by American composer Kate Soper, explores works by Aristotle, Plato, Freud, Wittgenstein, Jenny Holtzer, and Lydia Davis in an evening of theatrical chamber music. Alex Ross gets to the bottom of the performance in an article over at The New Yorker.

- A lost novella of Walt Whitman was recently discovered by grad student Zachary Turpin at the University of Houston. An anonymous work, Life and Adventures of Jack Engle: An Auto-Biography; In Which The Reader Will Find Some Familiar Characters (which is a fantastic name, we may add) was published in a New York newspaper in 1852 three years before Leaves of Grass.

- The National Portrait Gallery in London will be showcasing rare Old Master drawings, including those of Rembrandt and Leonardo da Vinci, in an exhibition The Encounter: Drawings from Leonardo to Rembrandt, starting July 13 of this year.

Figure studies by Rembrandt that will be on view at the National Portrait Gallery. (Credit: The Henry Barber Trust/Barber Institute/PA)

- Go! Go! Gilgamesh!, A Ragged Man production, takes place from February 15-28 during the 2017 FRIGID Festival of New York. Written by Phoebe Kreutz, the musical features a "super sexy cast" (including Kreutz herself) and "joke folk" songs.

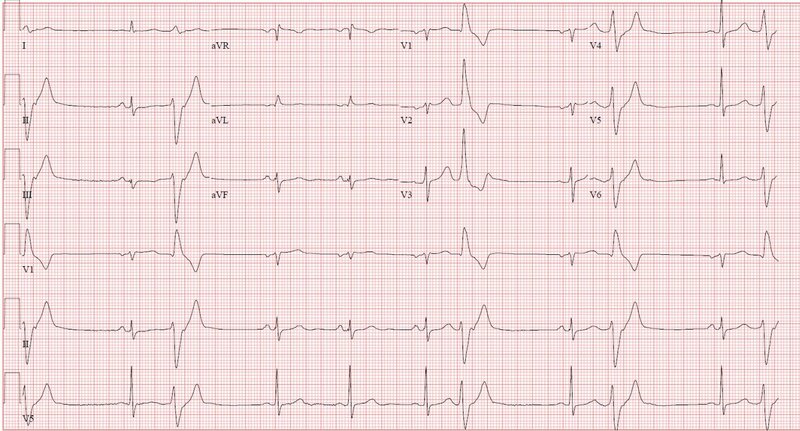

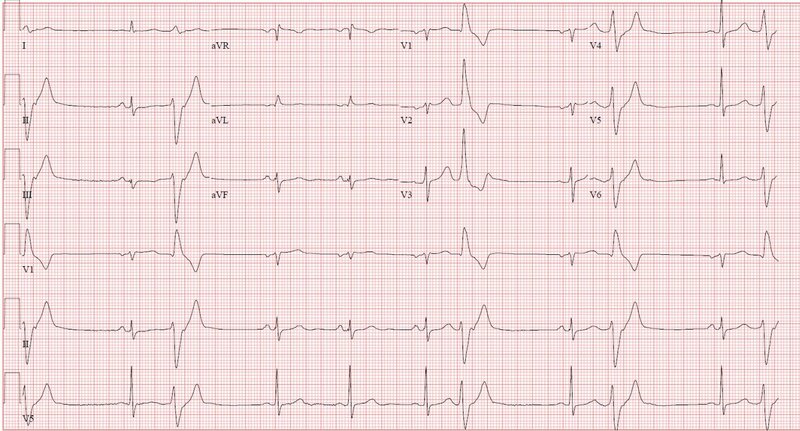

- A theory suggests that Beethoven may have suffered from cardiac arrhythmia, or more specifically a premature ventricular heartbeat, and that it influenced the "stuttering rhythms" of some of his works.

An electrocardiogram depicting multiple premature ventricular contractions. (Via Zach Goldberger)

That's all, folks! We hope you have a lovely last week before spring break.

By cdossett

|

Posted in Uncategorized

|

Tagged weekly links

|

February 23, 2017 at 10:56 am

Gary Taylor, lead general editor of The New Oxford Shakespeare, departs from the usual collections of Shakespeare's plays. For the first time, the three Henry VI plays add the name of Elizabethan tragedian and "bad boy of the English Renaissance," Christopher Marlowe, as co-author alongside the Bard. But that's not all--fourteen other plays from the 37-work canon feature other co-authors, including but not limited to Thomas Nashe, George Peele, John Fletcher, and several others.

Wild child. A 21-year-old Christopher Marlowe (allegedly) by an anonymous artist, 1585.

Do additional authors make Shakespeare's plays any less, well, Shakespeare? For many years now, various theories have cropped up regarding the playwright, including the Victorian era conspiracy that Shakespeare was more or less the pseudonym or public persona for an aristocrat, as New Yorker writer Daniel Pollack-Pelzner points out. Nowadays it is understood that a final screenplay, even from the sixteenth century, is the work of "many hands"--indeed, "individual hands" that the New Oxford Shakespeare has been able to identify. Another theory claims that Shakespeare's authority in Western literature stems from the mythology of the playwright rather than his skill, and that plenty of Renaissance writers existed who were just as good, if not better. But these aren't new ideas, Pollack-Pelzner tells us. Instead, the most interesting point that the New Oxford Shakespeare brings to the table is that:

[T]he canonization of Shakespeare has made his way of telling stories--especially his monarch-centered view of history--seem like the norm to us, when there are other ways of telling stories, and other ways of staging history, that other playwrights did better. If Shakespeare worshipers have told one story in order to discredit his contemporary rivals, the New Oxford is telling a story that aims to give the credit back.

The New Oxford Shakespeare hopes to challenge the assertion that Shakespeare is a flawless playwright. This belief is the same that prevents many of us from accepting that there may have been others at work alongside the Bard as he penned works that would be studied and performed for generations to come.

Read more about Marlowe as co-author of Henry VI and the mythology of Shakespeare in The New Yorker.

By cdossett

|

Posted in Core Authors, Great Books, Great Ideas

|

Tagged shakespeare

|

February 19, 2017 at 11:10 pm

One of the prime tasks of the literary critic is conservation; conservation of a tradition that has been formed in part by the books that have come from that very tradition. Yet this is a function that is wanting, alerts Professor Tony E. Afejuku, in African Literary Criticism.There are too many books in the inventory and not critics enough to catalogue them for the public and scholars. Another problem is the provincialism, nationalist and ethnic, that prevents African critics from identifying as such. What can we, the patron-saints of underrepresented books, do to help you, Professor Afejuku?

Illustration for The Guardian

Why do our contemporary critics wait for the West to applaud our writers before they themselves do so? We must now learn to discover our writers (and critics) for the West rather than the West doing the discovery for us. This is imperative for the growth of our contemporary literature and criticism. Indian literary scholars have been doing this for years. They do not wait for the West to tell them who is a good or talented Indian writer. They objectively and faithfully sell their writers to the West. Doing what I am hereby recommending will give Nigerian (and African) literary community its greatest happiness in no distant time.

Big Brother comes in two forms:one censors, the other patronizes. Afejuku writes before the closing no-thanks extracted above about the various ways in which critics at home can help African literature rise to its natural dignity, which means not depending onthe Western patronage that feels so solicitously obliged to dispense its charity. Could we atleast applaud that, Professor?

Read his full post at:

Thoughts on contemporary African Literary criticism

By Kush Ganatra

|

Posted in Uncategorized

|