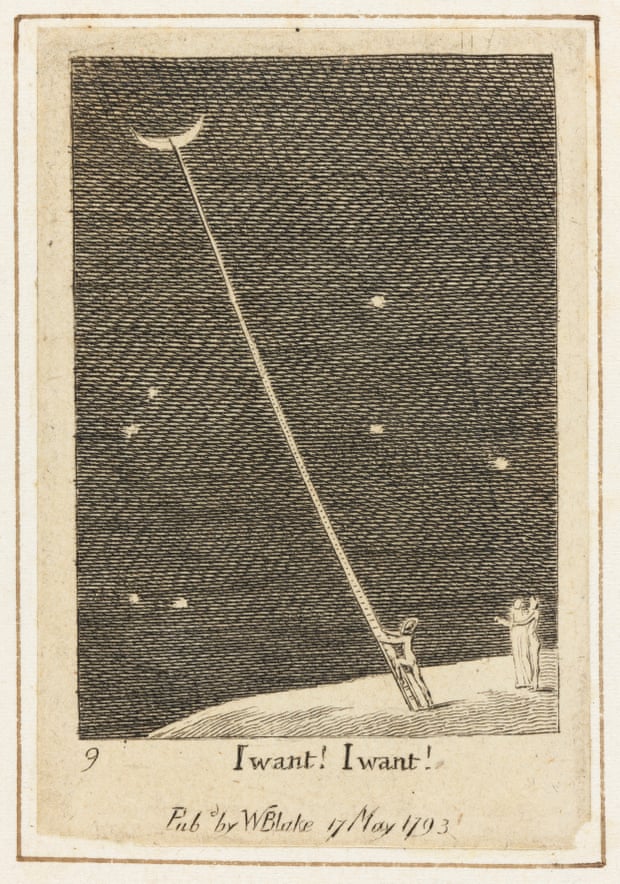

Rightly, Mary Beard in a recent article for the TLS takes for granted the question about whether the humanities should make it in the news at all. In a sense, it would be derogating from one of the signal purposes of the humanities if they were to be made the subject of more headlines. For if as Tennyson wrote, ‘Knowledge comes, but wisdom lingers,’ then in the welter of information we are routinely bombarded with it is likely that not only wisdom but knowledge too would linger. Are there honorable ways in which we can proffer the humanities without their coming to be degraded in this way? In other words, how does the Core Curriculum accomplish this?

I remember a few years back I was giving a lecture at a northern university (with a particularly active press office) on the Philogelos or Roman joke book. They had hyped the lecture in a big way, as new insights (which in some important ways it was). On the train up, journalists kept ringing my mobile. Their first question was: where had I found this text? The right answer was obviously I dug it up from the sands of Egypt. When I said that I found it on the library, they instantly lost interest even though I was doing something with the text that no one (I think) had done before.

What counts as new and newsworthy is the question.

And that is exactly what my own august university struggles with. They have just issued on the website a top 24 of Cambridge research stories this year. On my reckoning, 19 of those are pure science; and, of the rest, the majority are fascinating discovery or rediscovery stories (whether archaeology or a lost musical manuscript). Hang on I think, what are the rest of us doing? Does it really need to be under the radar, compared with (say) the mating call of mice? Youd think from looking at this roster that none of the work that some of us do rethinking Greek tragedy, or the demography of the medieval city, or the impact of T. S. Eliot counted for a hill of beans.

ya, or for a waste land. Didn’t get it? Exactly. I think Mary would agree that (say) any university harboring one of the top Eliot scholars in the world should try to stir some excitement when he or she publishes an authoritative two volume edition of his poetry. The humanities ask that we pause to ponder, and this does not preclude our thinking seriously about what is probably the “mating call” of the media: ‘innovation.’ It, like all things human and therefore of humanism and the humanities, must not monopolize our respect, but lose some when coming into competition with other things just as deserving of our honor, such as remembrance, sympathy, and a great reminder of all of the above, T.S. Eliot (though his erotic poetry isn’t much good).

Read her full post at The Times Literary Supplement