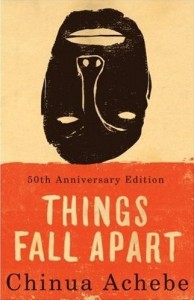

Cover of the paperback edition by Anchor Books

This month, EnCore's book club delved into Things Fall Apart, by the renowned and recently deceased Nigerian scholar Chinua Achebe. As described on the back of the paperback 50th Anniversary Edition from Anchor Books, the novel "tells two intertwining stories, both centered on Okonkwo, a 'strong man' of an Ibo village in Nigeria. The first, a powerful fable of the immemorial conflict between the individual and society...The second...concerns the clash of cultures and the destruction of Okonkwo's world with the arrival of aggressive European missionaries."

The discussion veered from cultural integration vs. negation to religion, from politics to colonialism, from narrative techniques to missionaries to reaching outer space. "Should we give medicine to isolated tribes?" and "Is the moon made of green cheese?" were only a few of the mysteries we perused, munching on wraps and drinking beer and wine in the AC-ed Core office this mild Wednesday night.

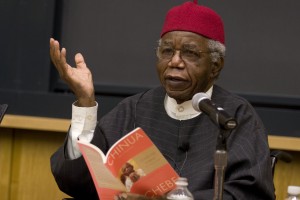

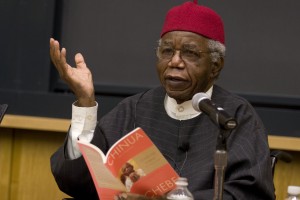

(Cambridge, MA - November 17, 2008) Novelist Chinua Achebe reads some of his poetry as the guest speaker. Staff Photo Nick Welles/Harvard News Office

Talking Points during the Discussion

We started off the discussion by musing on why the novel is often assigned to high schoolers in the United States, and is often listed as teen fiction and located in teen sections of libraries. Is it because, due to the narrative's seemingly simple language, it is an easily accessible example of foreign literature?

Speaking of which: why is is that this novel, one of the few examples of Nigerian literature widely read in America, has a title that can be considered an anthem to Western modernism, with all the trauma and seismic shifts the movement entailed? The title refers to one of the most famous poem's in the English language, "The Second Coming," written by W. B. Yeats.

During the evening, there were disagreements as to whether we are thrown into the stories and treated as fellow members of the tribe as we followed their victories and travails, or whether the narrative distances us from them, treating the characters as mere objects in the story, trapped under a museum diorama we can never quite access.

Can this story be considered an analogy, a warning folktale for the West as it exited the World Wars not-quite-unscathed? Or do we commit another colonial crime to think of it as such? Should we treat other cultures as museum pieces, in order to "preserve the traditions" we don't disagree with? Join us in our next meeting to voice your own opinion on another great work.

Deep in discussion

Memorable Quotes:

"Stories are how you transmit everything that defines a community."

(Someone pretending to talk to Okonkwo): "You are really embarrassing me in front of all these elders."

"The EU: the largest disaster ever."

Because everything else is accessible, "Space is the only place I can't get to."

"I'm going to argue against progress."

"How culturally unique is this story? The veteran is a dad who grew up poor and thinks his son is a sissy, and occasionally beats his wife. You can put the people almost anywhere."

"All people want is to feel empowered and safe."

On nostalgia: "The 50s: when men were men, and women liked it."

A quote from Buffy the Vampire Slayer: "Caesar didn't say, "I came, I saw, I conquered, and I felt bad about it."

Suspicious looks from a fellow attendee