By: Katherine Gianni

Before Yosef Abramowitz was a three-time Nobel Peace Prize nominee, an Israeli presidential hopeful, CEO of a major impact investment platform, or named one of CNN’s top six green pioneers worldwide, he was a student in Elie Wiesel’s classroom.

“I had the good fortune of being Elie Wiesel’s student in 1986, the year he won the Nobel Peace Prize,” Mr. Abramowitz recalled. “The name of the course was the Burden, Privilege and Responsibility of Rebellion. That really worked for me. He had such a strong moral grounding about the necessity to challenge.”

Mr. Abramowitz isn’t afraid to own up to his rebellious side, at least when it comes to creating what he refers to as, “the good kind of trouble.” On Tuesday, April 16, the Jewish educator, human rights activist, and environmentalist returned to his alma mater to speak and share stories with students on topics ranging from his days of chaining himself to Boston University President John Silber’s fence in an act of protest, to how to win today’s climate change battle.

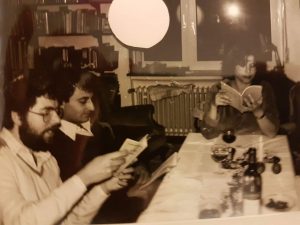

“There was a confluence when I was a student here of two big issues,” Mr. Abramowitz explained. “One was the fight of the freedom of Jews in the former Soviet Union. The other moral issue of the time, and perhaps the greatest moral issue of my generation, was apartheid in South Africa.”

Mr. Abramowitz and his fellow activists’ demands were clear: divestment of all university shares in companies that were profiting from the apartheid. The students organized rallies, made calls to other campuses urging for involvement, partook in hunger strikes, and even took over Mugar Library to spread their message.

“People in the university didn’t appreciate what we were doing,” Mr. Abramowitz explained. “They were like, “Well, what are you students really going to accomplish? What is this really going to do in the world?” Then what happened was Members of Congress started proposing sanctions legislation in response to this, like lots of Members of Congress.”

The Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 imposed sanctions on South Africa while outlining five preconditions for lifting said sanctions and ending apartheid. President Ronald Reagan vetoed the bill saying he favored “constructive engagement.” But then, Mr. Abramowitz explained, something tipped the scale.

“The only time Reagan’s veto was overturned was in his first term in office at the height of his popularity–it was on the sanctions against South Africa,” he said, smiling. “And that’s what students can do. I can’t say that when we were chaining ourselves to President Silber’s fence we were thinking about overturning Reagan’s veto, but just social movements–creating the wave and catching the wave, is really, really important.”

Mr. Abramowitz continues to ride the wave of activism today as CEO of Energiya Global Capital, a Jerusalem-based impact investment platform that provides returns to investors while furthering Israel’s environmentalism and advancing affordable green power to underserved populations as a fundamental human right. The organization was founded shortly after Mr. Abramowitz, his wife, Susan Silverman (CAS ‘85) and their five children moved over 5,000 miles across the globe from Newton, Massachusetts, to Kibbutz Ketura, Israel, in 2006.

“My family and I arrived to the Kibbutz right at sunset. We opened the air conditioned doors and boom we’re hit with this heat that was so disorienting,” Mr. Abramowitz explained. “The sun was just dipping and felt like superman laser beams going “woosh!” burning us to a crisp. At that point I had the thought, “Oh I’m sure the whole place works on solar power.””

Quickly, Mr. Abramowitz discovered that despite Israel being dubbed a “world leader” in solar technology, no one in the region was utilizing its power.

“The response I got was, “oh yeah, Israel’s a world leader in solar technology but no one’s crazy enough to take on the government,”” he explained. “Then I thought…the burden, privilege, and responsibility of rebellion…”

Mr. Abramowitz was crazy enough for the job. He teamed up with his business partners, Ed Hofland and David Rosenblatt, and together the three founded Arava Power Company. In 2011, the organization unveiled Israel’s first solar energy field at Ketura. Energiya Global Capital came next, with a goal of providing clean, sustainable solar energy for 50 million people by 2020.

“If someone could unlock the value, if someone can actually prove that it’s not out of reach, it’s actually doable, if something could change the paradigm, why not us?” he asked. “Why not us?”

A question and answer session followed Mr. Abramowitz’s remarks. A BU senior inquired about his approach to successful activism.

“What were some things that kept you going or helped you succeed during your activism battles and efforts?” she asked.

“Know what your values are,” Mr. Abramowitz answered. “If you believe in them, do something about it. I was privileged to be gifted these very powerful values at a time when they lead to action and world change. I think that’s been lost in this generation because social media make it too easy to like or dislike and you feel like, “Okay, I’ve already weighed in.” You cannot forget about the action.”

To learn more about Mr. Abramowitz, his work, and his hopes for the next generation visit http://www.bu.edu/today/2014/civil-disobedience-a-love-story/.