By: Katherine Gianni

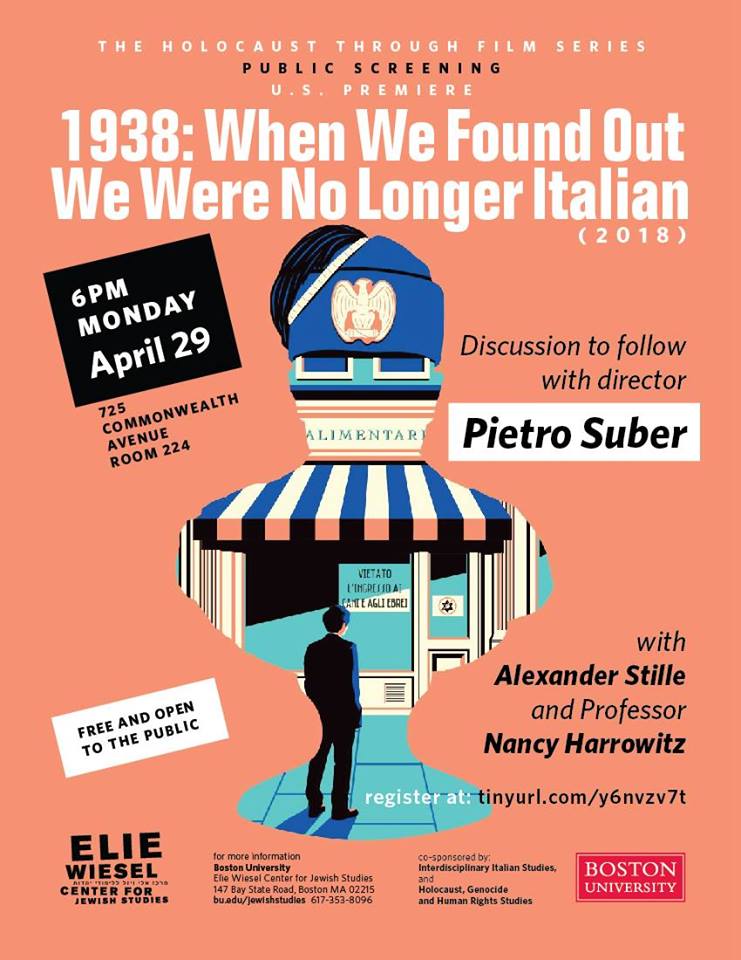

For the past three months Boston University students, staff, and community members alike have gathered in CAS room 224 for the Holocaust Through Film Series- an engaging selection of both classic and contemporary movies focused on the Holocaust. The series itself was planned and executed by Assistant Professor of French Jennifer Cazenave and Professor of Italian and director of Holocaust, Genocide, and Human Rights Studies Nancy Harrowitz. Last week, EWCJS sat down with Professor Cazenave to discuss the film selection process, the reactions from her students, and the importance of Holocaust education.

- How did the Holocaust Through Film series come about?

Professor Harrowitz and I research and teach in similar fields. She works a lot on Italian literature and film dealing with the Holocaust and I work on French cinema dealing with the Holocaust. We thought it would be nice for the two of us to collaborate and put a series together. Then the question was, what kind of series? Initially one of the titles we had for the series was something like, “Hollywood and Holocaust,” asking how Hollywood represents the Holocaust, and how do certain films resist Hollywood conventions. Another starting point for the series was that Prof. Harrowitz teaches a course on Holocaust and Cinema. Instead of students watching these films on their own, she thought why not have an actual film series.

- What was the process of choosing the films like?

We went back and forth with a lot of films. We added ‘1938: When We Found Out We Were No Longer Italian’ at the end because Dean Kirchwey was able to bring the director to campus. Once we dropped the Hollywood title, there was a sense that we needed some classics. Claude Lanzman’s Shoah is a classic documentary. Our Children is also a classic because it was made in 1948, only three years after the war ended, and because it’s in Yiddish, which is really crucial because the disappearance of the Yiddish language is also a kind of extermination. People were exterminated, but also an entire culture disappeared with them. It was important for us to include a film in Yiddish. It’s such a unique film. I also think the theme of children, and of children surviving and making sense of trauma, was important to show. Prof. Harrowitz and I also thought it would be important for the younger generation to think about how can we continue to represent the Holocaust? There are now so many Holocaust films now. You know, for me, for my generation, it was Schindler’s List. I remember being 14 and seeing Schindler’s List, so every generation has a film or has had a film…but maybe that’s less so today. We have films, but I feel like there’s not that one, where if we interviewed BU undergrads they’d be like, “Oh, it’s this particular film.”

- How did your students respond to the series?

I think they loved it. I think The Matchmaker was their favorite, I think because of the story it tells and the characters, and the way in which it tries to present the Holocaust in ways people have not seen because again if you go on Netflix you will find I don’t know how many Holocaust films, but there is also a general genre of what a Holocaust film looks like, but then you have these kinds of films that try to do it completely differently. The ones that stand out will be the ones that try to find a new form.

- Did you have a favorite film out of the six that were shown?

People always, always ask me. It’s always hard for me to have a favorite. What I really liked about 1945 is that it’s minimalist, it’s beautiful, but you get so much emotion, especially seeing the villagers’ perspective and then seeing these two men. I just loved the simplicity and the way the filmmaker builds on this idea that we don’t know what’s in the casket that they bring with them to the train station and that they’re carrying throughout the film. In cinema, you have this idea of the offscreen…so you have your frame and then anything that’s outside of it is the offscreen. So Shoah, for example, plays with the offscreen because you don’t have archival images. So you have this sense that there’s something looming. It’s not like what you don’t see doesn’t exist. On the contrary! French film theory says that the frame actually conceals as much as it shows. Great films are films that play with the offscreen. And that’s what I loved about 1945.

- Why do you think Holocaust education through film is important?

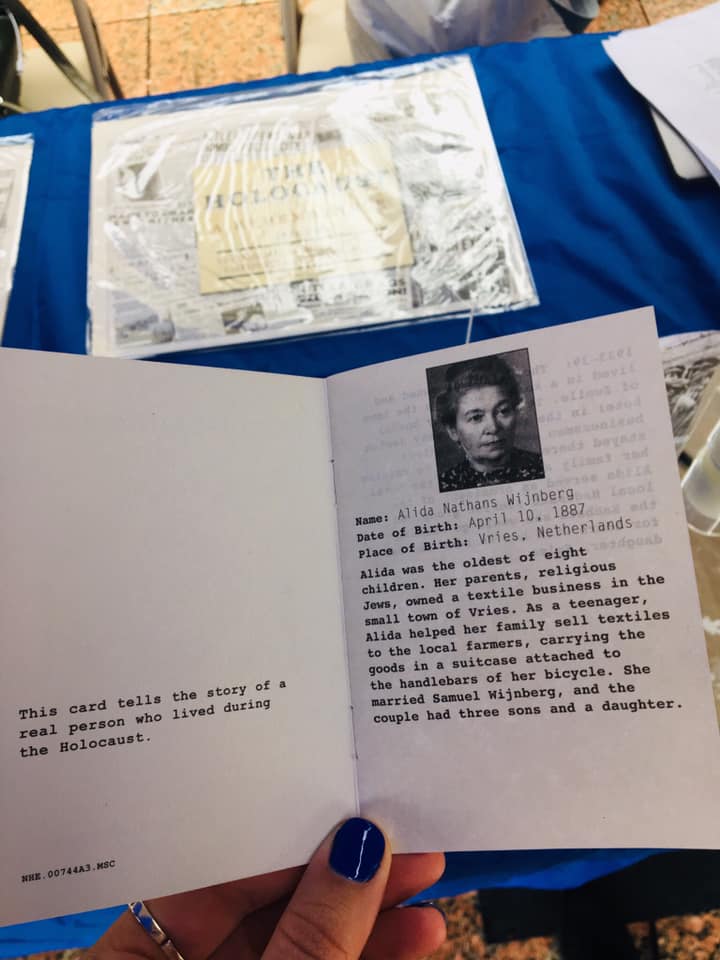

I think film is a great medium for history in general and it’s constantly evolving. At USC in LA they have a Shoah Foundation that Spielberg started following the success of Schindler’s List. He pledged to collect 50,000 testimonies of survivors. So it became the biggest repository of oral histories. But now the big question is how do we maintain the memory of the Holocaust, as survivors are dying. And so what USC has been doing is to make holograms, which basically means that someone is filmed over the course of three days. They have to wear the same clothes, sit in the exact same way, and are filmed. And then you can actually interact with the survivors…they’ve been placing these interactive holograms in museums around the country to test them. There’s a thick binder with all of the questions so I tested one at the Holocaust museum in DC. It’s more interesting to see young children react to this because they think it’s Skype or Facetime.

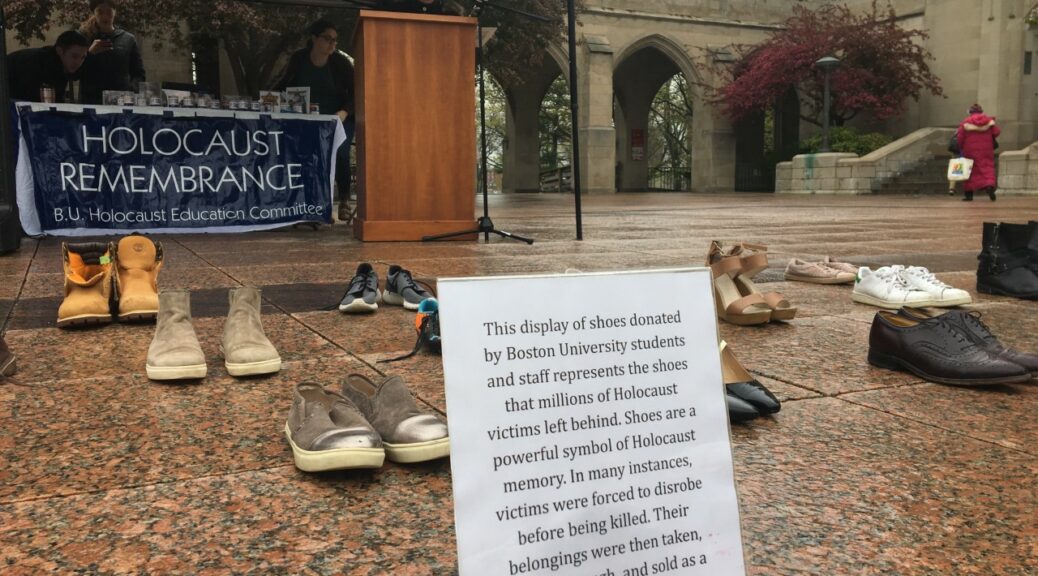

However, there is something about film, whether it’s a movie or an interview that creates a personal connection. Books do that as well, but there is a way in which you may be marked by images or you might get more attached to characters if you see them. For me there is really something about the memory of the Holocaust being dependent upon film and there’s something that film can salvage. I also like the collective experience because when you read a book you may come to class and discuss it, but it was something else to have our students and people from the community come for Shoah and then being able to present the film and answer all of these technical questions. There was something about it. I think the collective aspect, which we’re losing more and more, was really important. There’s something for me about the experience and being more moved by that. Books can also be extremely moving, but I think the topic lends itself very well to being experienced through film.