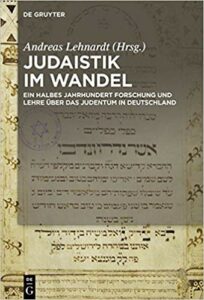

Andreas Lehnardt, ed. Judaistik im Wandel: Ein halbes Jahrhundert Forschung und Lehre über das Judentum in Deutschland. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017. vi + 239 pp. $80.99 (cloth), ISBN 978-3-11-052103-0.

Reviewed by Alan T. Levenson (University of Oklahoma) Published on H-Judaic (November, 2019) Commissioned by Katja Vehlow (University of South Carolina)

Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=54267

This multi-authored volume, ably edited by Andreas Lehnardt (Johannes Gutenberg Universität, Mainz) comprises the revised conference proceedings held at the Maimonides Institute of the University of Hamburg in 2015. The sixteen contributions chronicle the study of Judaic and Jewish studies in Germany over the past fifty years, exactly as the subtitle promises. (How I wish “Judaistik” were an English word, if only to end the scholastic debate between which term, “Judaic” or “Jewish,” is preferable.) This volume offers a bird’s-eye view of the current state of affairs, including essays on Yiddish, Kabbalah, music, sociology, and the Second Temple period, and occasionally offers deeper insights into the location of these studies in the wider world of scholarship.

Shmuel Feiner’s introduction, “Jüdische Studien heute: Eine Perspektive aus Israel 2015” (Jewish studies today: A perspective from Israel in 2015), provides a provocative typology of Jewish studies in Israel and in the United States, and in a more tentative vein, in Germany. Feiner presents American Jewish studies as ultimately a celebration of globalism and pluralism, optimistic and diasporic. Whereas Judaistik in Israel has largely freed itself from the Zionist dogmatism of the Jerusalem school, the scholarship remains bound up in conflicts, crisis, and culture wars of Israeli society—which Feiner nevertheless considers the place best situated to take the pulse of Jewish life. The tendency of German Judaistik seems less clear, although one may observe a fault line between Andreas Lehnardt, Rafael Arnold, Walter Homolka, and Elke Morlok, who offer sustained reflections on their scholarly relationship with the nineteenth-century founders of Wissenschaft des Judentums, and the many other essays that hit on this central vein only occasionally.

Rafael Arnold’s “Die Forschung zur sephardischen Sprache, Literatur und Kultur” (Research on Sephardic language, literature, and culture) makes the interesting point that in Spain itself, Judeo-Spanish was seen as a corrupt dialect (Abart), whereas German scholars, having direct contact with Judeo-Spanish speakers in Hamburg, Vienna, and the Balkans, had a greater appreciation for Judeo-Spanish. Arnold points to the irony of this appraisal with respect to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century attitudes toward Yiddish. Arnold likewise presents a helpful thumbnail sketch of the research commenced before the Shoah by Meyer Kayserling, Max Leopold Wagner, Leo Spitzer, of course Fritz (Yitzhak) Baer, and others. Given the title of his essay, Arnold might have added a few lines on the differences between Ladino, Judeo-Spanish, and Judeo-Arabic in the Middle East and North Africa. He shares the generally upbeat assessment of Jewish studies as a flourishing enterprise in Germany, which provided partial motivation for this volume, and which I find convincing.

Nathaniel Riemer calls for more attention to material culture in his “Brauchen die Jüdischen Studien einen weiteren ‘turn?’” (Are Jewish studies in need of another “turn?”). Riemer’s discussion of seder plates, prayer books, and school rooms illuminates, but one may wonder if Riemer attacks a straw man as the study of material culture has been on the rise in Jewish and general studies for some time—in Germany and elsewhere. As has often been the case, Jewish studies has lagged behind methodologically. For this one may offer many reasons, but that gap seems to have closed.

Tal Ilan’s account of her projected feminist commentary to the Babylonian Talmud fascinates: who outside the field of Talmud knew that a ninety-one volume series of this sort was projected and that twenty-nine tractates have already been assigned or published? One can only admire a scholar who sees this as a desideratum in Jewish studies. Commenced in 2005, this project stuns in its ambition, although Ilan regrets that the project has lost momentum: in her view, due to the absence of Jewish gender studies in Germany. Given that a feminist commentary is unlikely to win many readers in the yeshiva world, one may wonder if the number of readers could have far exceeded the number of authors had this project succeeded. Ilan offers in this essay, as usual, more than she promises, and includes excellent discussions of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Simone de Beauvoir, Grace Aguilar, and Judith Plaskow as champions of scriptural learning from a women’s perspective. That Ilan and several others in this volume received their training in Israel or the United States seems worth mentioning; this scholarship takes place in Germany but not in a vacuum.

Noam Zadoff’s essay on Israel studies strikes the right note between realism and aspiration: “Any analysis of Israel Studies in Germany must take into account that at the moment this field is almost non-existent in this country. On the one hand this means that the field has all its future ahead and there are reasons to be optimistic.” Zadoff briefly describes the emergence of Israel studies since the 1980s, and in greater detail, the genesis of the five positions as Israel studies in Germany. His sanguine view is grounded in the sound observation that “Israel Studies is probably the most rapidly growing and most dynamic part among the branches of Jewish Studies worldwide” (p. 81). Zadoff further explains the historiographical trends, the organizational dimensions, and the politics—for good and bad. Borrowing Assaf Likhovski’s language, he makes the case that we now have a “post-post-Zionist historiography” (p. 85). One may hope that we can someday approach regular historiography regarding Israel, rather than requiring a third postal prefix.

We have here an insightful and reliable guide to what is going on in the world of German and German–speaking scholarship, right down to places and persons, as in Marion Aptroot’s “Jiddisch an deutschen Universitäten” (Yiddish at German universities). Most German Judaicists have studied and/or lectured in Israel and/or America and acknowledge their debt to the predominantly Jewish founders of the field, the master workers, as S. Y. Agnon put it. Both factors play a positive role, requiring more explicit discussion than the format of this volume permits. Structurally, the essays in the section titled “Perspektiven und Plädoyers” (Perspectives and pleas) could as easily be found in the section titled “Impulse” and vice versa. The sole chapter on Bible studies arrives as the penultimate entry, Giuseppe Veltri’s essay on skepticism needs more context for the non-expert, and missing altogether is a chapter on medieval Jewry, a lacuna given the prominence of that topic in German scholarship, traditionally and today.

Useful as a reference book or a who’s who, Judaistik im Wandel presents the written record of what was probably an exciting conference. But the whole is the sum of its parts.

Alan T. Levenson holds the Schusterman/Josey Chair in Judaic history at the University of Oklahoma.

Citation: Alan T. Levenson. Review of Lehnardt, Andreas, ed., Judaistik im Wandel: Ein halbes Jahrhundert Forschung und Lehre über das Judentum in Deutschland. H-Judaic, H-Net Reviews. November, 2019. URL:http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=54267

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.