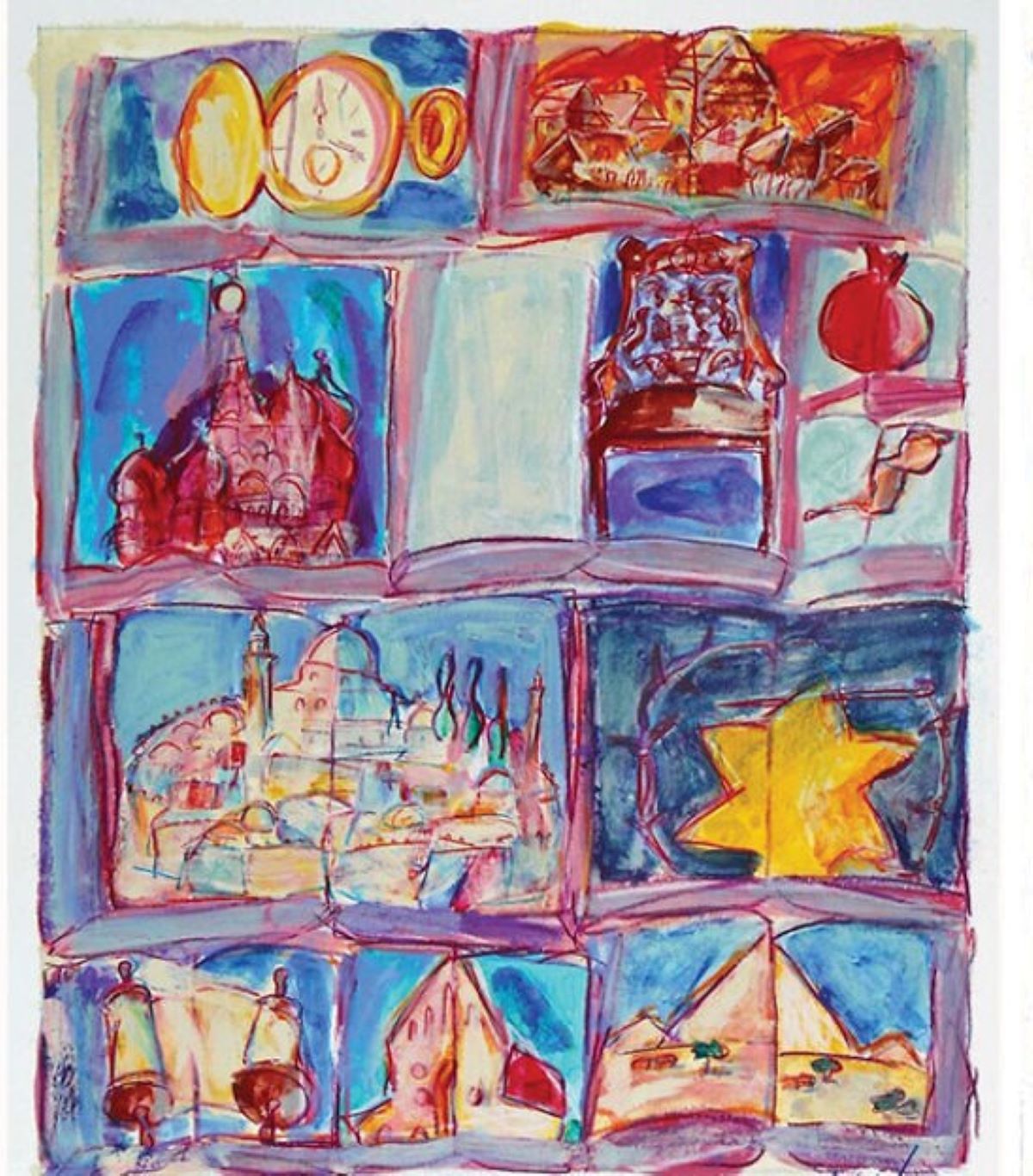

Physician, artist and friend of Elie Wiesel Mark Podwal describes working closely with Elie Wiesel and how he came to create “The Books of Elie Wiesel”

Here’s the painting;

Physician, artist and friend of Elie Wiesel Mark Podwal describes working closely with Elie Wiesel and how he came to create “The Books of Elie Wiesel”

Here’s the painting;

by Deni Budman (COM '20)

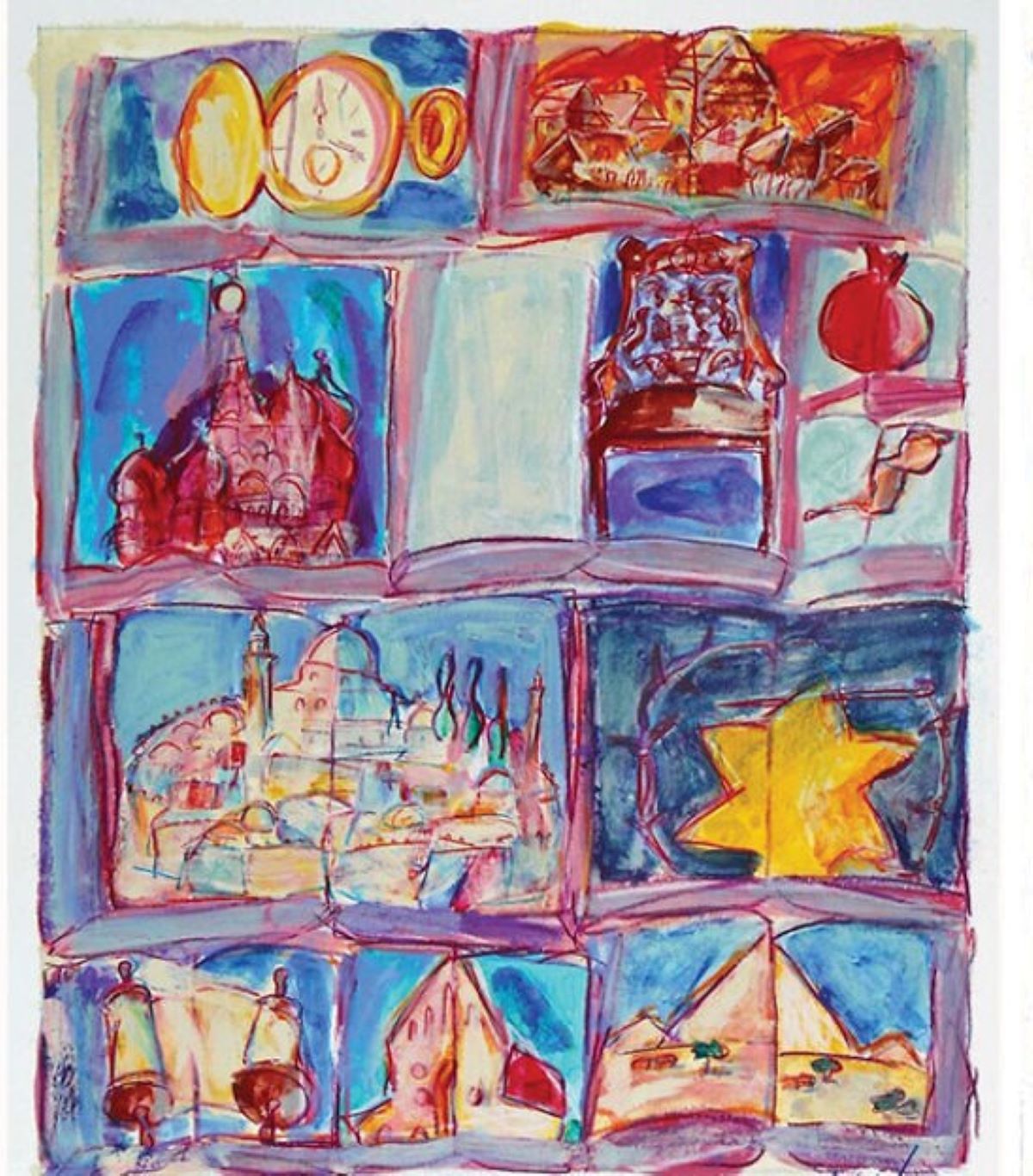

Classes like JS286 / HI393 Israeli-Palestinian Conflict are hard to come by. The course topic presents a unique challenge: how to teach an international conflict in an engaging and unbiased way. The way it is taught at BU does just that.

The history of the conflict in the Middle East is taught with conflicting narratives using primary sources and film. It is a blend of historical context and contemporary political analysis. Throughout the course, students present their own reflections on the conflict and debate possibilities of resolution.

Professor Nahum Karlinsky, who has taught the course for several years, has mastered the art of pushing his students to come to their own conclusions; supported, of course, with all the necessary background knowledge to make informed decisions.

David Tay (COM ‘22), a student in the current spring 2020 course, says, “One of the biggest realizations that I’ve come across is that this conflict is incredibly hard to define in American political terms. With most topics debated in America, it comes down to a Republican perspective and a Democratic perspective. The Israeli Knesset alone has dozens of parties, and that’s not including the dozens of different Palestinian and Arab groups who are also stakeholders, but aren’t necessarily represented in the Knesset. There have been several times where I caught myself trying to put historical events into two-sided conflicts when in reality, it’s never actually that simple.”

Practically every student who’s taken the course agrees that one of the best parts of the class is the environment of discussion. Students break up into small groups to dissect assigned readings, and they are often surprised to see how others interpreted the same text differently. These discussions culminate at the end of the course in a staged peace conference.

Dynnor Shebhsaievitz (CAS ‘20), another current student, enjoyed being able to learn about the conflict from a historical perspective as opposed to the emotional perspective she knew from before. She chose this class because she “felt that would help me shape my own opinion while learning to respect others.”

When asked why students should take this course, Professor Karlinsky joked that they should take other more fun courses such as cooking classes. But, “If they want to learn about one of the most contentious and well-known conflicts in our contemporary world, from both Palestinian and Israeli perspectives, in a balanced, informed but also engaging (so I hope) manner, they should sign up, now!”

We agree. Sign up for JS286 and other Jewish Studies classes for the Fall 2020 semester!

More info about Jewish Studies course HERE

And HERE is all you need to know about which Jewish Studies course fulfill which HUB requirements.

JS286 / HI393 counts toward majors and minors in History, International Relations, Middle East & North Africa Studies, and Jewish Studies. The course fulfills a single unit in each of the following BU Hub areas: Historical Consciousness, Global Citizenship and Intercultural Literacy.

Tallulah Bark-Huss (COM ‘21) interviewed Dr. Katharina von Kalllenbach, the speaker for the BU Jewish Studies Forum On February 18 at 2:30 PM at the Elie Wiesel Center.

The title of Dr. von Kalllenbach’s talk is Der Nestbeschmutzer: Guilt and Transformation in Post-War German Discourse, and she will delve into what it means to confront your own country’s wrongdoings.

The German word, “Nestsbeschmutzer,” literally means a person who soils the nest. In English, one might say, “whistleblower,” “leaker,” or “mole.” It refers to someone who sheds light on, or is critical of, the indiscretions of their own culture. The word refers to “dirt” and evokes a need to cleanse the people who do the soiling. Calling someone out for soiling the nest implies that if they don’t talk about the subject, things will remain clean.

The use of words such as “dirt” and “cleansing” was used in post-Holocaust discourse when Germany had to face the question: What do we do with all these Nazis? The Nazis also saw the Holocaust as an act of ethnic purification. Dr. von Kellenbach says she wants to think about these images and this language when discussing coming to terms with guilt. While working on her book on the mark of Cain, she wondered, “What is it with this stain that can’t be washed off? How can I think about guilt in a way that does not cleanse it out of history?” She wants to investigate the trope of brushing the past under the rug as she finds this idea is still very much relevant today.

Today, the same cleansing language is used. However, Dr. Von Kellenbach thinks it’s important to use a different metaphor and instead prefers to say “composting” when thinking about guilt. In composting, the dirt isn’t brushed away but is used to create something new.

Dr. von Kellenbach thinks this conversation is important to have, especially for a younger audience, because the desire for purification on college campuses is so present. “There is a lot of puritanism [on college campuses]. [There is a lot of] political correctness and who we declare to be ‘dirt.’ A lot of desire to be pure is powerfully present on campus.”

But, beyond college campuses, the political climates in America and other countries are frighteningly familiar. “We have Charlottesville where people run around with Nazi paraphernalia as if the past 70 years hadn’t happened. And in Germany, it’s as if we’re right back at square one.” The country is in the midst of a political crisis. Its political state is fragmenting more and more as became evident when Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s chosen successor, resigned this past week. According to a Vox article, “The center-right CDU voted with the far-right, anti-immigrant, anti-Islam Alternative for Deutschland (AfD) to install a member of the smaller, pro-business Free Democrats as state premier.” This surprising turn of events points to the German far-right faction’s growth and foreshadows Germany’s uncertain future.

Dr. Katharina von Kellenbach, Professor of Religious Studies at St. Mary’s College of Maryland and the Corcoran Visiting Chair in Christian-Jewish-Relations at Boston College 2019-2020, says the current political climate in Germany evokes the ghosts of the country’s stained past and points to the lessons Germany has not learned. For the last twenty years, her research has focused on the perpetrator-side of the Holocaust.

On the eve of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Israeli Consul General to New England Zeev Boker delivered the following remarks at Boston University where Ambassador Boker helped to unveil the "Beyond Duty” exhibition. The opening of the exhibition preceded a lecture by Prof. Michael Grodin (MED, SPH, EWCJS) and a panel of international diplomats commemorating those who went “beyond duty,” often defying their own governments, to issue life-saving documents that allowed thousands of Jews to escape Nazi persecution.

Good afternoon. I wish to thank AJC New England and Boston University for partnering with us to present this important program today and for launching the “Beyond Duty” exhibition. I also wish to thank all of our speakers and in particular, the consuls general for being a part of the panel, and I especially wish to welcome Holocaust survivors.

![PHOTO-2020-02-10-18-36-03[2]](/ewcjs/files/2020/02/PHOTO-2020-02-10-18-36-032-225x300.jpg) International Holocaust Remembrance Day, which occurs tomorrow, January 27, marks the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, the largest Nazi death camp during World War II. Close to one million Jews were murdered there. Indeed it was the State of Israel in 2005 that took the initiative at the United Nations to establish this day of global remembrance in order to ensure that the nations of the world will honor the memory of Holocaust victims while rejecting Holocaust denial and commit to preventing future genocides. Indeed, It is a tribute to the tenacity of Israeli diplomats led by Roni Adam that the UN finally gave its approval to International Holocaust Remembrance Day, which was initially met with resistance in the General Assembly.

International Holocaust Remembrance Day, which occurs tomorrow, January 27, marks the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, the largest Nazi death camp during World War II. Close to one million Jews were murdered there. Indeed it was the State of Israel in 2005 that took the initiative at the United Nations to establish this day of global remembrance in order to ensure that the nations of the world will honor the memory of Holocaust victims while rejecting Holocaust denial and commit to preventing future genocides. Indeed, It is a tribute to the tenacity of Israeli diplomats led by Roni Adam that the UN finally gave its approval to International Holocaust Remembrance Day, which was initially met with resistance in the General Assembly.

To honor the memories of the 6 million Jewish victims of the Holocaust, the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in collaboration with Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial museum, created the exhibition “Beyond Duty.” Yad Vashem honors not only the memory of victims but also those who resisted and fought back against the Nazis. In addition, Yad Vashem gives special recognition to those selfless non-Jewish individuals who, at great personal risk to themselves and their families aided and rescued Jews. These heroes are known as “Righteous Among the Nations,” and close to 27,000 have been so recognized.

When I served as Israeli Ambassador in Slovakia, it was my privilege on International Holocaust Remembrance Day to confer official recognition of “Righteous Among the Nations” upon individuals who saved Jewish lives: they included bishops and clergy as well as simple farmers and city folks who related incredible stories of hiding Jews, including in holes in the ground.

Among those recognized as “Righteous Among the Nations” were 34 diplomats from a variety of countries. A few of these brave diplomats, such as Chiune Sugihara and Raoul Wallenberg are known to many, but there were others whose names are not known, and it is important that their legacies be brought to light as well. It is hard to overestimate the multiplier effect of the actions of the diplomats who saved thousands of Jewish lives.

While most countries of the free world were reluctant to help Jewish refugees during WWII, and while most diplomats continued to employ standard procedures, only a very few felt that extraordinary times required extraordinary action and were willing to act against their governments’ policies, and suffer the consequences. Moreover, they did so in the context of a war-time totalitarian Nazi regime where their very lives were at stake. Their stories inspire us today as they represent the power of the individual to do the right thing in the face of the darkest and most evil chapter of our recent past.

The Exhibition that you witnessed here today at BU represents the first time this is being shown in New England, and will be open from tomorrow until February 6 at the State House in Boston.

“Beyond Duty” teaches us that we are not alone. On a regional level, the Consulate is proud of our partnerships with elected officials, major Jewish organizations and opinion leaders in New England to combat Anti-Semitism. A majority of the New England states, including Massachusetts, recently passed resolutions pledging to combat anti-Semitism and to adopt the definition of anti-Semitism set forth in the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, or “IHRA.” The IHRA consists of a comprehensive definition that includes all types of contemporary antisemitism, including anti-Zionism, and is a meaningful tool in the fight against antisemitism, both in education, political discourse and in the field of law enforcement.

Last week, Israeli President Reuven Rivlin welcomed 40 world leaders to Jerusalem who came to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. This was a tremendous show of solidarity and commitment on the part of the international community to preserve the memory of the Jewish lives lost in WWII. These leaders, including the American Vice President and the Speaker of the House of Representatives, signaled a deep commitment to fighting anti-Semitism, Holocaust denial and racism. President Rivlin thanked them for their solidarity with the Jewish people and for their commitment to Holocaust remembrance. He noted the critical role that the Allies played in defeating Nazism and in liberating the camps. In his words: “Antisemitism does not stop with the Jews. Anti-Semitism and racism are a malignant disease that destroys and pulls societies apart from within, and no society and no democracy is immune.” He went on to describe Israel as a “state that looks for partnership—that demands partnership,” and he described the Jewish people as “a people that remember.” Unfortunately, the Jewish people understand what it is NOT to remember since history repeats itself. President Rivlin urged all countries to officially adopt the IHRA definition of anti-Semitism and make efforts to work according to it.

Today we are gathered together to draw inspiration from the courage of the Righteous Diplomats as we honor their moral choices and explore ways to walk in their footsteps. May the memories of our brothers and sisters who perished in the Holocaust and those who waged war on Nazism, be forever engraved in our hearts. The Jewish people are strong and the State of Israel remains committed to ensuring that Never Again truly means Never Again.

Ling is a senior BU student who is completing her Bachelor’s degree in History with a minor in Jewish studies. Her current research focus is on American Jewry and their relations with the state of Israel during the post-WWII era. As an international student, Ling is always excited to meet new friends and engage in friendly conversations with people from diverse backgrounds. She loves challenging herself to be a better learner and listener.

I never experienced anti-Semitism at BU. However, the reason why I became a Jewish studies minor was that I used to have friends who were anti-Semites and Holocaust deniers while I was studying at Georgia State University. I understood those people befriended me precisely because I was not Jewish. Anti-Semitism today is not just carried out by white supremacists like we usually think, but also by people of color. My anti-Semitic "friends" were Chinese, Laotian, and Arab immigrants. Many of them came from torn-apart families and experienced extremely tough situations, which created the perfect condition to allow hatred and bias to settle in.

Using the umbrella term “anti-Semitism” to identify the driving force behind hundreds of years of Jewish suffering is not sufficiently detailed and compelling for me. After careful studies of Jewish history, I believe that anti-Semitism is an expression or consequence of discontent, and rarely a motivation for action in and by itself. It is only through real causes like religious fanaticism, nationalism, a failing economy, or something as personal as ignorance or false assumptions that anti-Semitism survives and evolves throughout history.

Whatever the agenda with regard to Israel or anti-Semitism that President Trump and his son-in-law and senior advisor, Jared Kushner, may be pursuing, it seems to me that they are appealing to a certain Jewish “victim mentality” that is rooted in the experience of the Holocaust. I completely understand the enduring legacies of histories of persecution and genocide. However, I am also very concerned about how this toxic victim mentality prevents us from reflecting on ourselves objectively.

Anti-Semitism thrives on ignorance and indifference. We live in a dangerous world, but I believe that students are strong enough to overcome victim mentalities and actively educate themselves and people around them. Since I became a Jewish studies minor, I often brought non-Jewish BU students to Temple Ohabei Shalom and encouraged them to communicate with local congregants after Friday night service. As they learned more about the diverse and fascinating Jewish culture in America, they became willing to defend Jewish people, religion, and values.

Israel and Zionism are not the only principles that define all aspects of Jewish life in America, Morocco, France, Iraq, and all the other beautiful Jewish communities globally. Criticizing Israel may help Israel see its past or current mistakes and hence prevent the repetition of history. I really wish the best for Jewish communities in Israel, America, and elsewhere. Part of what is needed for Jews and non-Jews is to form alliances, including with other minority groups. For this to happen may require for Jews to be more open to criticism of Israel.

I will end with an old Chinese saying: “Although good medicine cures sickness, it is often unpalatable; likewise, sincere advice given for one's wellbeing is often resented."

by Michael Zank

On December 10, it was a shooting at a kosher Deli in Jersey City, New Jersey. On the seventh night of Hanukah, it was a machete attack on Hasidic Jews in Monsey, New York. In both incidents, people were targeted not as individuals but because they were Jews. Why has there been so little response to these events? Have our leaders and pundits become inured to violence against Jews, just as non-Muslim society has become inured to violence against Muslims, white society to violence against African Americans, and straight people to violence against LGBTQ people? Has our sense of a commonwealth shrunk to the size of tribes that we can no longer see the maiming of an orthodox Jew as an attack not on their world, but on ours?

Our first obligation is to comfort the mourners. At times like these, we are particularly consoled by acts of cross-communal solidarity. Muslims forming a human chain around a synagogue in Pittsburgh. Jews raising money for the victims of the Christchurch, New Zealand, mosque attack. It matters that our solidarity crosses communal lines. It signals we are in this together. No one should feel alone and abandoned in the face of senseless acts of violence. We must reach out to one another and assure those attacked: you are not alone. This must be our message today, especially for our students: you are not alone! We are here and we are with you. You are loved, and you are safe.

Perhaps the silence can be explained by the fact that Rockland County, Jersey City, and other New York suburbs represent a special case. As has been widely reported, Hasidic Jews– the fastest-growing segment of the American Jewish community– have been displaced from their native Brooklyn by the skyrocketing costs of real estate. As Hasidic Jews move to the suburbs, many locals are priced out. The response among some politicians has been to cash in on the growing anti-Hasidic resentment. Their rhetoric has since crossed the line into anti-Semitic territory. Incendiary rhetoric has an effect. It incites blind and indiscriminate hatred against an entire community. In this case, against an exclusive religious community widely perceived as recreating old world shtetls in modern America. But the disagreements, such as differences over school boards and housing developments, that arise between long standing community members and their new neighbors need to be resolved in a civil manner. We call on both Hasidic and non-Hasidic suburbanites of New York and New Jersey to resolve their differences peacefully. In the interest of our commonwealth. We also call on politicians to curb their rhetoric and refrain from further incitement. All of us must resist the rhetoric of polarization and the temptation of tribalism.

Let these most recent acts of violence be a wake-up call to all of us. Violence means failure. There are social consequences to economic inequality and to the rhetoric of exclusion. We must return to building a more just, more capacious society, together. We must settle our differences with civility. And today, we offer our solidarity to our Hasidic brothers and sisters. May they be comforted among the mourners of Zion.

In the photo attached to this post: A woman holds candles while standing in solidarity with the victims after an assailant stabbed five people attending a party at an Hasidic rabbi's home in the hamlet of Monsey, in the town of Ramapo, N.Y. (Amr Alfiky/Reuters)

Levenson on Lehnardt, 'Judaistik im Wandel: Ein halbes Jahrhundert Forschung und Lehre über das Judentum in Deutschland' [review]

Levenson on Lehnardt, 'Judaistik im Wandel: Ein halbes Jahrhundert Forschung und Lehre über das Judentum in Deutschland' [review]Andreas Lehnardt, ed. Judaistik im Wandel: Ein halbes Jahrhundert Forschung und Lehre über das Judentum in Deutschland. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017. vi + 239 pp. $80.99 (cloth), ISBN 978-3-11-052103-0.

Reviewed by Alan T. Levenson (University of Oklahoma) Published on H-Judaic (November, 2019) Commissioned by Katja Vehlow (University of South Carolina)

Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=54267

This multi-authored volume, ably edited by Andreas Lehnardt (Johannes Gutenberg Universität, Mainz) comprises the revised conference proceedings held at the Maimonides Institute of the University of Hamburg in 2015. The sixteen contributions chronicle the study of Judaic and Jewish studies in Germany over the past fifty years, exactly as the subtitle promises. (How I wish “Judaistik” were an English word, if only to end the scholastic debate between which term, “Judaic” or “Jewish,” is preferable.) This volume offers a bird’s-eye view of the current state of affairs, including essays on Yiddish, Kabbalah, music, sociology, and the Second Temple period, and occasionally offers deeper insights into the location of these studies in the wider world of scholarship.

Shmuel Feiner’s introduction, “Jüdische Studien heute: Eine Perspektive aus Israel 2015” (Jewish studies today: A perspective from Israel in 2015), provides a provocative typology of Jewish studies in Israel and in the United States, and in a more tentative vein, in Germany. Feiner presents American Jewish studies as ultimately a celebration of globalism and pluralism, optimistic and diasporic. Whereas Judaistik in Israel has largely freed itself from the Zionist dogmatism of the Jerusalem school, the scholarship remains bound up in conflicts, crisis, and culture wars of Israeli society—which Feiner nevertheless considers the place best situated to take the pulse of Jewish life. The tendency of German Judaistik seems less clear, although one may observe a fault line between Andreas Lehnardt, Rafael Arnold, Walter Homolka, and Elke Morlok, who offer sustained reflections on their scholarly relationship with the nineteenth-century founders of Wissenschaft des Judentums, and the many other essays that hit on this central vein only occasionally.

Rafael Arnold’s “Die Forschung zur sephardischen Sprache, Literatur und Kultur” (Research on Sephardic language, literature, and culture) makes the interesting point that in Spain itself, Judeo-Spanish was seen as a corrupt dialect (Abart), whereas German scholars, having direct contact with Judeo-Spanish speakers in Hamburg, Vienna, and the Balkans, had a greater appreciation for Judeo-Spanish. Arnold points to the irony of this appraisal with respect to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century attitudes toward Yiddish. Arnold likewise presents a helpful thumbnail sketch of the research commenced before the Shoah by Meyer Kayserling, Max Leopold Wagner, Leo Spitzer, of course Fritz (Yitzhak) Baer, and others. Given the title of his essay, Arnold might have added a few lines on the differences between Ladino, Judeo-Spanish, and Judeo-Arabic in the Middle East and North Africa. He shares the generally upbeat assessment of Jewish studies as a flourishing enterprise in Germany, which provided partial motivation for this volume, and which I find convincing.

Nathaniel Riemer calls for more attention to material culture in his “Brauchen die Jüdischen Studien einen weiteren ‘turn?’” (Are Jewish studies in need of another “turn?”). Riemer’s discussion of seder plates, prayer books, and school rooms illuminates, but one may wonder if Riemer attacks a straw man as the study of material culture has been on the rise in Jewish and general studies for some time—in Germany and elsewhere. As has often been the case, Jewish studies has lagged behind methodologically. For this one may offer many reasons, but that gap seems to have closed.

Tal Ilan’s account of her projected feminist commentary to the Babylonian Talmud fascinates: who outside the field of Talmud knew that a ninety-one volume series of this sort was projected and that twenty-nine tractates have already been assigned or published? One can only admire a scholar who sees this as a desideratum in Jewish studies. Commenced in 2005, this project stuns in its ambition, although Ilan regrets that the project has lost momentum: in her view, due to the absence of Jewish gender studies in Germany. Given that a feminist commentary is unlikely to win many readers in the yeshiva world, one may wonder if the number of readers could have far exceeded the number of authors had this project succeeded. Ilan offers in this essay, as usual, more than she promises, and includes excellent discussions of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Simone de Beauvoir, Grace Aguilar, and Judith Plaskow as champions of scriptural learning from a women’s perspective. That Ilan and several others in this volume received their training in Israel or the United States seems worth mentioning; this scholarship takes place in Germany but not in a vacuum.

Noam Zadoff’s essay on Israel studies strikes the right note between realism and aspiration: “Any analysis of Israel Studies in Germany must take into account that at the moment this field is almost non-existent in this country. On the one hand this means that the field has all its future ahead and there are reasons to be optimistic.” Zadoff briefly describes the emergence of Israel studies since the 1980s, and in greater detail, the genesis of the five positions as Israel studies in Germany. His sanguine view is grounded in the sound observation that “Israel Studies is probably the most rapidly growing and most dynamic part among the branches of Jewish Studies worldwide” (p. 81). Zadoff further explains the historiographical trends, the organizational dimensions, and the politics—for good and bad. Borrowing Assaf Likhovski’s language, he makes the case that we now have a “post-post-Zionist historiography” (p. 85). One may hope that we can someday approach regular historiography regarding Israel, rather than requiring a third postal prefix.

We have here an insightful and reliable guide to what is going on in the world of German and German–speaking scholarship, right down to places and persons, as in Marion Aptroot’s “Jiddisch an deutschen Universitäten” (Yiddish at German universities). Most German Judaicists have studied and/or lectured in Israel and/or America and acknowledge their debt to the predominantly Jewish founders of the field, the master workers, as S. Y. Agnon put it. Both factors play a positive role, requiring more explicit discussion than the format of this volume permits. Structurally, the essays in the section titled “Perspektiven und Plädoyers” (Perspectives and pleas) could as easily be found in the section titled “Impulse” and vice versa. The sole chapter on Bible studies arrives as the penultimate entry, Giuseppe Veltri’s essay on skepticism needs more context for the non-expert, and missing altogether is a chapter on medieval Jewry, a lacuna given the prominence of that topic in German scholarship, traditionally and today.

Useful as a reference book or a who’s who, Judaistik im Wandel presents the written record of what was probably an exciting conference. But the whole is the sum of its parts.

Alan T. Levenson holds the Schusterman/Josey Chair in Judaic history at the University of Oklahoma.

Citation: Alan T. Levenson. Review of Lehnardt, Andreas, ed., Judaistik im Wandel: Ein halbes Jahrhundert Forschung und Lehre über das Judentum in Deutschland. H-Judaic, H-Net Reviews. November, 2019. URL:http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=54267

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

By Abigail Gillman

In the brutal nights we used to dream

Dense violent dreams,

Dreamed with soul and body:

To return; to eat; to tell the story.

Until the dawn command

Sounded brief, low

'Wstawac'

And the heart cracked in the breast.

From: Primo Levi, “Reveille”

These lines, which comprise the first stanza of Primo Levi’s poem “Reveille,” lay at the center of the second Elie Wiesel Memorial Lecture of 2019. The poet recalls the prisoners’ dreams of returning home, eating, and telling the stories, interrupted each dawn by the Polish command. But the three repetitions of the word “dream,” argues Sharon Portnoff, also allude to three dreams in Dante’s Purgatorio: dreams which enable the pilgrim to ascend to paradise. In Dante, the dream represents the power to imagine, to tell the story of hell, in a way that preserves dignity and redeems suffering.

How did Dante help Levi to survive, and to write about the hell of Auschwitz? In Portnoff’s words, “Levi’s poem – as almost all of his writings do – draws on the texts of the Western canon to invite us to literally engage the fact of Auschwitz against the backdrop of our higher aspirations, to spend our time reading and studying his many allusions. We do this not to find out what the human being really is in the midst of his suffering, but to enact what the human being might be.”

Dante’s Hell, and Levi’s hell: as Dante is inscribed throughout Primo Levi’s oeuvre, Levi’s writings, his poetry, his two memoirs, become a commentary or education about Dante. Levi’s turn to Dante recalls the approach of another child survivor, Israeli writer Aharon Appelfeld, who referred to Franz Kafka as his redeemer, and who copied from the Hebrew Bible in his quest to become a writer.

When a great writer translates or interacts with another great literary work, there is a magic or alchemy which is hard to put into words. Portnoff owned this challenge, teaching us various approaches one might take and inviting us in to her own process of interpretation.

In doing so, she continued the narrative begun by Rabbi Joseph Polak in the first lecture back in September. Polak spoke about memory, and unexpectedly, about shame. Though he has authored an award-winning memoir, Polak taught us that he continues to think about how to tell his story, and is still retrieving, or receiving, new memories from the war, which he survived as a very young child. The sound of counting aloud in German, heard on a recent trip to Germany, evoked a visceral reaction, an aural memory of the Appelplatz, the prisoners’ roll call, which, according to his mother, he attended daily as a young boy, sitting on the shoulders of a Nazi soldier.

Rabbi Polak also spoke, provocatively, about shame as the most damaging, lasting injury the Nazis perpetrated on their victims. By implication, those of us who were not there need to ask whether we continue the shaming by not being fully present to survivors.

In these lectures, we learn not only about the survivor, but about the power and limits of language for the survivors of genocide, and for those of us who engage with their writings. The speakers challenge us to hear those stories in new ways; to wake up, as Levi’s poem implores; and to become more human in the process.

Abigail Gillman is Professor of Hebrew and German in the Department of World Languages and Literatures and a core member of the faculty of the Elie Wiesel Center for Jewish Studies where she teaches courses in modern Jewish and Hebrew literature. She served as interim director of the Center in 2016-17 and directed the university-wide Day of Learning and Commemoration for Elie Wiesel in September 2017. Her most recent book is A History of German Jewish Bible Translation (University of Chicago Press, 2018).

By Jennifer Cazenave

On April 17, 1975, the Khmer Rouge entered the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh, marking the beginning of a four-year brutal regime led by Pol Pot. In an attempt to transform the country into an agrarian utopia, the Khmer Rouge displaced millions of Cambodians to forced labor camps in the countryside. By January 6, 1979, an estimated 1.7 million people had perished from famine, forced labor, torture, disease, and execution; they were buried in mass graves known as killing fields.

The decade-long civil war following the end of the Khmer Rouge regime delayed recognition of the genocide, both locally and globally. The memory of the genocide began to emerge in the 1990s and 2000s, notably through the testimonies of survivors included in documentary films or published as memoirs. Transnational war crimes tribunals were also established in Cambodia in 2003, marking the beginning of a lengthy judicial process to investigate the atrocities and prosecute Khmer Rouge leaders.

Loung Ung was born in Phnom Penh in 1970. Along with her family, she was forced to evacuate the capital in April 1975. She survived the genocide as a child, before escaping Cambodia in 1979 and coming to the United States a year later. In 2000, she told her story of survival in a memoir published in English, which she titled First They Killed My Father. Her book was adapted into an eponymous film directed by Angelina Jolie in 2017.

On Monday, November 18, 2019, forty years after the end of the Khmer Rouge regime, we will welcome Loung Ung to BU. Her talk will conclude our fall series “Writing from a Place of Survival” and allow us to commemorate the genocide in Boston—a city situated an hour away from Lowell, which is home to the second largest Cambodian community in the United States.

Tsai Performance Center, 7:30-9pm.

The event is free and open to the public but pre-registration is strongly recommended. To register, follow this link. (Alumni status NOT required.)

Jennifer Cazenave is Assistant Professor of French. Her first book, An Archive of the Catastrophe: The Unused Footage of Claude Lanzmann’s “Shoah” (SUNY Press, 2019), undertakes a comprehensive examination of the 220 hours of filmic material Claude Lanzmann excluded from his 1985 Holocaust opus. Professor Cazenave is currently at work on a second book project that examines the centrality of the earth as a medium for the writing of the Cambodian genocide in the cinema of Rithy Panh. Her article titled “Earth as Archive: Reframing Memory and Mourning in The Missing Picture,” which examines Panh’s autobiographical representation of the catastrophe, recently appeared in Cinema Journal.

All you need to know about Dante Alighieri (d. 1321) is that his Divine Comedy ranks as the greatest literary work in the Italian language. This does not mean you need to have read part or all of it in order to follow Sharon Portnoff’s talk on October 28. There won’t be an exam at the end. Our public-facing talks are meant to provide us with food for thought, not make us feel insufficient. We will be in good hands: Sharon Portnoff has read Dante. So did Primo Levi.

Who was Primo Levi? Primo Levi (1919-1987) was an Italian chemist who, in February 1944, at the age of 24, was captured by Italian fascists, handed over to the Nazis, and deported to Auschwitz. Following liberation by the Red Army on January 27, 1945, he eventually made his way back to his native Torino where he wrote poetry, worked in a paint factory, and, as early as 1947, published his meticulous and sober account of life as a slave laborer in the Buna camp (se questo é un uomo). The second edition (1958) was more widely distributed, including in English, French, and a German translation he closely supervised. Levi went on to write other acclaimed books, including The Periodic Table (1975), The Drowned and the Saved (1986), among others. He died in 1987 of a fall into the stairwell of his home. The circumstances of his untimely death remain disputed.

What does Levi have to do with Dante? Levi’s prose style is dispassionate, as one might expect from a scientist. But he has recourse, at important junctures, to the poetry of Dante, whose Inferno perceptively describes the kinds of psychological horrors and absurdities that were realized in a camp system whose sole purpose was dehumanization, esp. the dehumanization of Jews.

As we planned the 2019 Elie Wiesel Memorial Lecture series on “writing from a place of survival,” we felt that it was important to recall Primo Levi. We are looking forward to Sharon Portnoff’s lecture on Monday, October 28, 7:30pm, at the Tsai Performance Center. Please reserve your seat!