http://archives.bu.edu/web/elie-wiesel/videos/video?id=424828

Tag Archives: Elie Wiesel

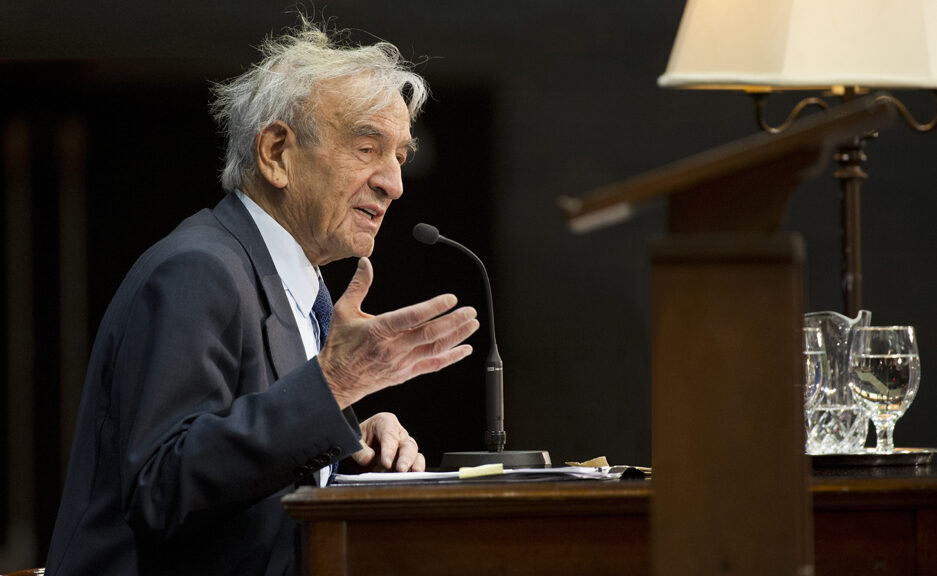

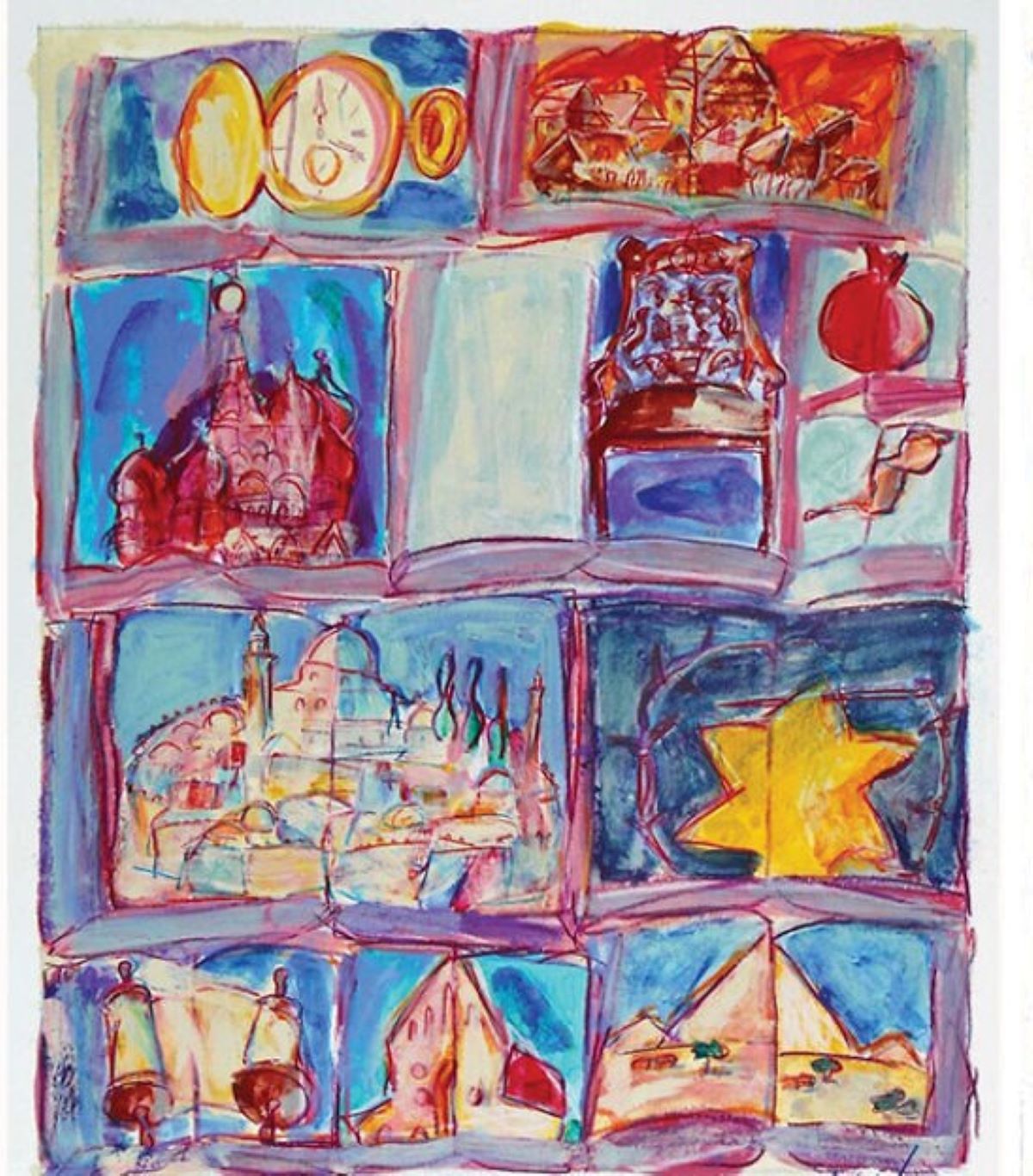

Making the Books of Elie Wiesel

Physician, artist and friend of Elie Wiesel Mark Podwal describes working closely with Elie Wiesel and how he came to create “The Books of Elie Wiesel”

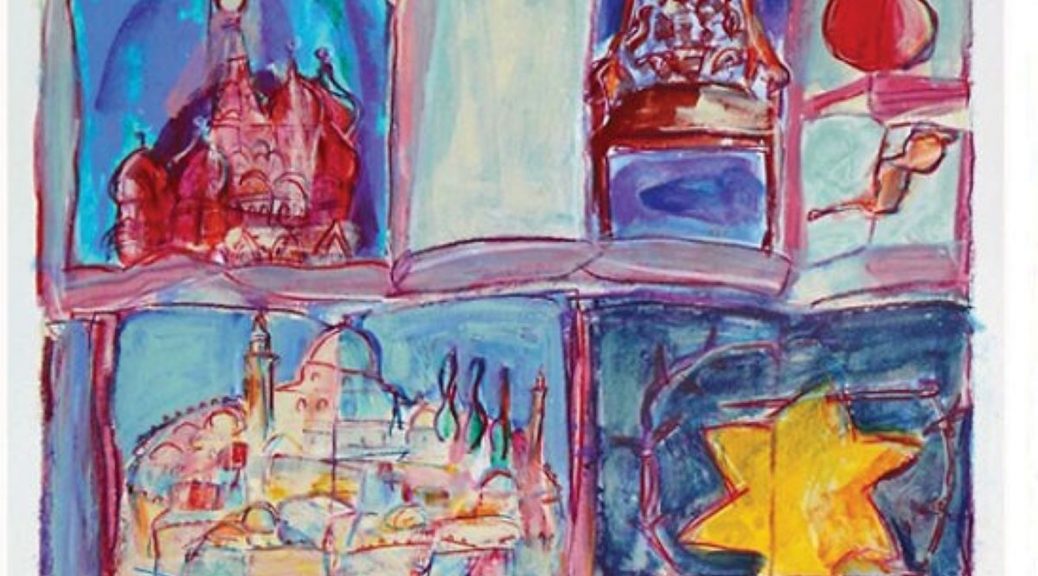

Here's the painting;

Holocaust Through Film Series Calls for Collective Engagement and Reflection

By: Katherine Gianni

For the past three months Boston University students, staff, and community members alike have gathered in CAS room 224 for the Holocaust Through Film Series- an engaging selection of both classic and contemporary movies focused on the Holocaust. The series itself was planned and executed by Assistant Professor of French Jennifer Cazenave and Professor of Italian and director of Holocaust, Genocide, and Human Rights Studies Nancy Harrowitz. Last week, EWCJS sat down with Professor Cazenave to discuss the film selection process, the reactions from her students, and the importance of Holocaust education.

- How did the Holocaust Through Film series come about?

Professor Harrowitz and I research and teach in similar fields. She works a lot on Italian literature and film dealing with the Holocaust and I work on French cinema dealing with the Holocaust. We thought it would be nice for the two of us to collaborate and put a series together. Then the question was, what kind of series? Initially one of the titles we had for the series was something like, “Hollywood and Holocaust,” asking how Hollywood represents the Holocaust, and how do certain films resist Hollywood conventions. Another starting point for the series was that Prof. Harrowitz teaches a course on Holocaust and Cinema. Instead of students watching these films on their own, she thought why not have an actual film series.

- What was the process of choosing the films like?

We went back and forth with a lot of films. We added ‘1938: When We Found Out We Were No Longer Italian’ at the end because Dean Kirchwey was able to bring the director to campus. Once we dropped the Hollywood title, there was a sense that we needed some classics. Claude Lanzman’s Shoah is a classic documentary. Our Children is also a classic because it was made in 1948, only three years after the war ended, and because it’s in Yiddish, which is really crucial because the disappearance of the Yiddish language is also a kind of extermination. People were exterminated, but also an entire culture disappeared with them. It was important for us to include a film in Yiddish. It’s such a unique film. I also think the theme of children, and of children surviving and making sense of trauma, was important to show. Prof. Harrowitz and I also thought it would be important for the younger generation to think about how can we continue to represent the Holocaust? There are now so many Holocaust films now. You know, for me, for my generation, it was Schindler’s List. I remember being 14 and seeing Schindler’s List, so every generation has a film or has had a film...but maybe that’s less so today. We have films, but I feel like there’s not that one, where if we interviewed BU undergrads they’d be like, “Oh, it’s this particular film.”

- How did your students respond to the series?

I think they loved it. I think The Matchmaker was their favorite, I think because of the story it tells and the characters, and the way in which it tries to present the Holocaust in ways people have not seen because again if you go on Netflix you will find I don’t know how many Holocaust films, but there is also a general genre of what a Holocaust film looks like, but then you have these kinds of films that try to do it completely differently. The ones that stand out will be the ones that try to find a new form.

- Did you have a favorite film out of the six that were shown?

People always, always ask me. It’s always hard for me to have a favorite. What I really liked about 1945 is that it’s minimalist, it’s beautiful, but you get so much emotion, especially seeing the villagers’ perspective and then seeing these two men. I just loved the simplicity and the way the filmmaker builds on this idea that we don’t know what’s in the casket that they bring with them to the train station and that they’re carrying throughout the film. In cinema, you have this idea of the offscreen...so you have your frame and then anything that’s outside of it is the offscreen. So Shoah, for example, plays with the offscreen because you don’t have archival images. So you have this sense that there’s something looming. It’s not like what you don’t see doesn’t exist. On the contrary! French film theory says that the frame actually conceals as much as it shows. Great films are films that play with the offscreen. And that’s what I loved about 1945.

- Why do you think Holocaust education through film is important?

I think film is a great medium for history in general and it’s constantly evolving. At USC in LA they have a Shoah Foundation that Spielberg started following the success of Schindler’s List. He pledged to collect 50,000 testimonies of survivors. So it became the biggest repository of oral histories. But now the big question is how do we maintain the memory of the Holocaust, as survivors are dying. And so what USC has been doing is to make holograms, which basically means that someone is filmed over the course of three days. They have to wear the same clothes, sit in the exact same way, and are filmed. And then you can actually interact with the survivors...they’ve been placing these interactive holograms in museums around the country to test them. There’s a thick binder with all of the questions so I tested one at the Holocaust museum in DC. It’s more interesting to see young children react to this because they think it’s Skype or Facetime.

However, there is something about film, whether it’s a movie or an interview that creates a personal connection. Books do that as well, but there is a way in which you may be marked by images or you might get more attached to characters if you see them. For me there is really something about the memory of the Holocaust being dependent upon film and there’s something that film can salvage. I also like the collective experience because when you read a book you may come to class and discuss it, but it was something else to have our students and people from the community come for Shoah and then being able to present the film and answer all of these technical questions. There was something about it. I think the collective aspect, which we’re losing more and more, was really important. There’s something for me about the experience and being more moved by that. Books can also be extremely moving, but I think the topic lends itself very well to being experienced through film.

Holocaust Remembrance Day Recognized Across BU Community

By: Katherine Gianni

Grey skies and passing showers did nothing to deter those recognizing Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, on Thursday morning in Marsh Plaza.

Hosted by the Elie Wiesel Center for Jewish Studies and Boston University Hillel, students and community members alike were invited to light a candle, say a prayer, or remember a loved one who may have perished in the Holocaust. A ceremonial Reading of the Names began as Marsh Chapel’s bell tower chimed 9:00 a.m.

Miriam Angrist, a senior lecturer in Hebrew and Head of the Hebrew Language Program was one of the first people up at the podium.

“I’m reading the names of those who’ve perished to show that I will not allow them to be forgotten,” she said, her words echoing across the expanse of the plaza. One by one she recited the names from a booklet as thick as a dictionary. Hillel student president Connor Dedrick said that each participant will read for 10 minutes, getting through approximately 100 to 150 names.

“At the end of the day we leave a bookmark where the last reader finished up,” he explained. “In one year it’s impossible to get through all the names we have in this book. It normally takes six to seven years to read every single name.”

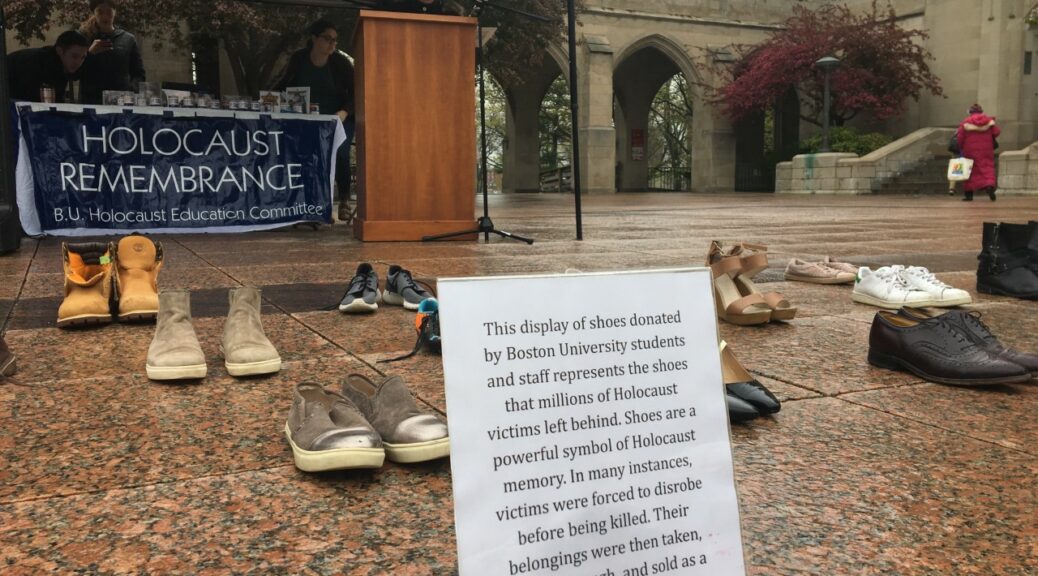

Rows of shoes were displayed in front of the podium to symbolize the millions of Holocaust victims. Hillel Holocaust Education Chair Tallulah Bark-Huss explained that shoes are often used in Holocaust museums and memorials around the world to commemorate those who lost their lives.

“The shoes themselves were donated by various BU students,” she said. “In many instances, Jews were told to take off their shoes before being killed. A famous memorial is in Budapest called the Shoes on the Danube Bank, so I was inspired, in part, by that. I felt like we should utilize all of the space we have here at Marsh Plaza.”

As the observance continued, one student approached the array of sandals, boots, and sneakers to add a pair of his own.

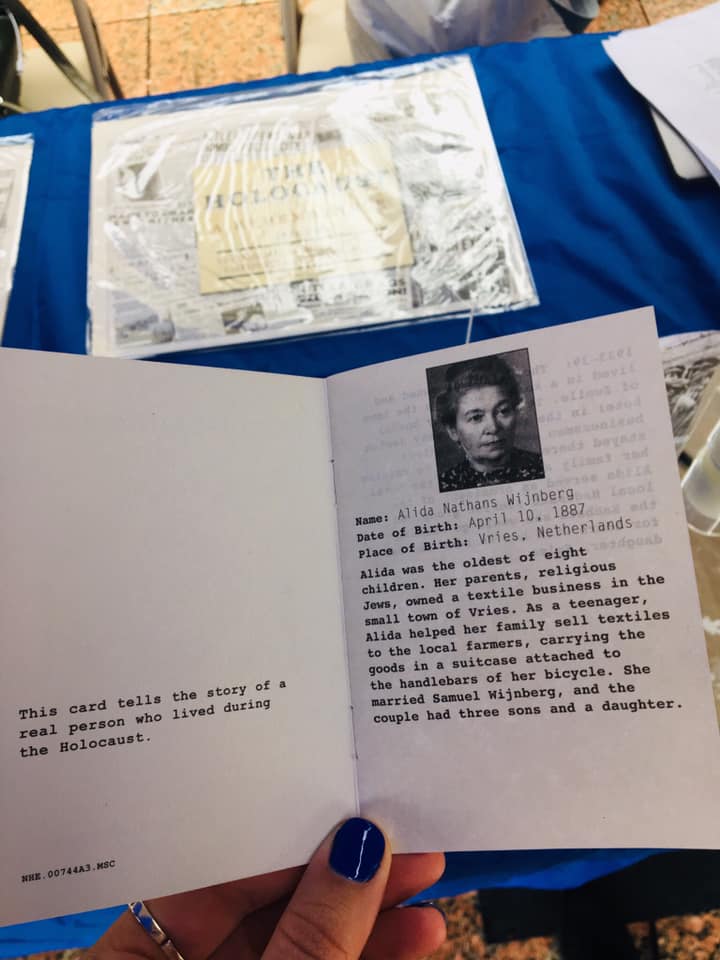

Two tables sat behind the podium, both showcasing an array of photographs, candles, and even identification cards from the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. Each card tells the story of a real person who lived through the Holocaust. BU senior Carmelle Dagmi, who organized the event two years ago, offered the cards to passersby.

“I really hope that when people come by today that they participate and help to keep the memory alive,” she said. “I feel like I have a personal responsibility to hear the names and remember the stories.”

Mr. Dedrick read his share of names following Professor Angrist. She stood alongside the display in quiet reflection.

“This means the world to me because not only do I recognize Remembrance today, I live it on a daily basis,” she said. “We are a community that gets together on special occasions, both sad and happy. I hope that people really just take a moment to reflect.”

At 5:00 p.m., event organizers, students, faculty and staff will convene for a short ceremony which will include speakers, poetry, and candle a lighting. All are welcome to join. For more information visit https://www.bu.edu/hillel/calendar/.

Words on the Occasion of the 2019 Marsh Plaza Candle Lighting

By: Michael Zank

I saw a wonderful show yesterday at the Paramount in Downtown Boston. It was called peh LOH tah, a futbol framed freedom suite by Marc Bamuthi Joseph and the Living Project. It featured a combination of dance, spoken word, song, and visual projection, using soccer, a sport that connects so many people across the globe, as a source of inspiration to speak about the condition of people of color, about the vulnerability of migrants, about economic justice, and “Black joy.” One of the memorable lines I remember went like this: People can imagine the end of the world before they can imagine the end of capitalism.

Why am I telling you this?

Because to me, Holocaust remembrance is about the imagination. Without imagination, we cannot see, we cannot connect. Without imagination, we cannot recall the past, and we cannot project ourselves into a future that is significantly different from the past or the present. There can be no change without imagination.

My father in law, who is a 98-year-old emeritus professor of mathematics, was born in Warsaw and grew up in Sosnoviec, Poland, not far from Krakow and hence also not far from Oswiecim, better known as Auschwitz. In 1943 he was rounded up and delivered to what in Jewish camp jargon was referred to as “the yeshive,”an SS camp called Gross Rosen, from where the SS would distribute young healthy Jews as slave laborers to a myriad of labor camps dotting the border region between Poland and the Czech Republic. My father in law ended up at the woodworking factory Hubert Land at Bunzlau. Working on heavy machines he could forget for hours at a time that he was no longer a human being. In early 1945, along with about 440 others, he was marched across German-occupied territory and ended up in Bergen Belsen, which was liberated by the British on April 15, 1945. That was the day my father in law’s humanity was restored. (On the Boleslawiec/Bunzlau camp see HERE , HERE, and HERE.)

Over the years, Abe told many stories, mostly about people of courage to whom he owed his life. A young woman who secretly left him a container of hot soup, fearful of being recognized as his benefactress. A German soldier who threw him a loaf of bread, pretending it was a gesture of contempt rather than an act of kindness. The SS officer inspecting the factory and hearing Abe out as he explained, in imperfect German, why the machines had ceased to work. People with infinite courage, as he used to say, who saw him in his “striped pajamas” but recognized him as human.

Abe always emphasized that most human beings suffer from a lack of imagination.

Holocaust Memorial Day stimulates our imagination. We are meant to put ourselves in the place of the victims. We are reminded of their names, their lives, their civilization, built over the course of a millennium and destroyed in a mere twelve years.

Today, despite an increase in anti-Semitic incidents, Jews are strong, accepted, and even privileged. America has been an unprecedentedly welcoming home for Jews. We also have a Jewish state. Israel’s economy and her military are among the strongest in the Middle East. Israeli democracy is as vibrant as can be.

The question I am asking myself today is this: Do we have enough imagination to see ourselves not just as a people of survivors but as the privileged agents that we actually are? Are we invested in speaking on behalf of others who have no voice or who are silenced by bullies? Are we attentive to our own white privilege and are we finding ways of empowering others? If we are able-bodied, can we see people with disabilities as fully human? As employers, do we treat our employees with respect?

The Holocaust was an extreme case of dehumanization. But dehumanization happens everywhere and all the time, and we must resist it where we see or participate in it, whether it is in the world of work, or in our all-too-segregated communities, or somewhere else. The original Yiddish version of Elie Wiesel’s world-famous memoire Night, bore the title And the World Was Silent. (Un di Velt hot geshvign.) Will we be silent, or will we speak? To speak on behalf of others requires imagination. I requires that we care.

As we remember the six million dead, the million and a half Jewish children murdered, exterminated in ways that are unspeakable and unimaginable, let us commit to speaking out on behalf of the many who are dehumanized, tortured, neglected, and forgotten today. Humanity is not a fact we can take for granted. It is a task we must make our own, over and over again, little by little, and person by person.

Let us commit to speaking out. Let us not remain silent. Let us stand up to the purveyors of hate. Resist those who tell us this country is full. Let us resist those who claim there is moral equivalence between white supremacists and those who oppose white supremacy. Let us resist anti-Semitism in every form and fashion, but let us also resist those who want us to fall in line as they target others for their religion, their place of origin, or their sexual orientation. Our Law commands us to love, not to despise or exclude, the stranger, for s/he is like you. As we remember the Holocaust, we also remember that we were not the only ones singled out for destruction.

Let us attend to our history, not ignore or forget. Those who forget are doomed to repeat. But let us also study, learn, and listen to the histories of others as if they were our own.

Today, at Marsh Plaza, near a monument to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., let us mourn our dead, and recommit to the protection of civil and human rights for all.

Yosef Abramowitz’s Burden, Privilege, and Responsibility of Rebellion

By: Katherine Gianni

Before Yosef Abramowitz was a three-time Nobel Peace Prize nominee, an Israeli presidential hopeful, CEO of a major impact investment platform, or named one of CNN’s top six green pioneers worldwide, he was a student in Elie Wiesel’s classroom.

“I had the good fortune of being Elie Wiesel’s student in 1986, the year he won the Nobel Peace Prize,” Mr. Abramowitz recalled. “The name of the course was the Burden, Privilege and Responsibility of Rebellion. That really worked for me. He had such a strong moral grounding about the necessity to challenge.”

Mr. Abramowitz isn’t afraid to own up to his rebellious side, at least when it comes to creating what he refers to as, “the good kind of trouble.” On Tuesday, April 16, the Jewish educator, human rights activist, and environmentalist returned to his alma mater to speak and share stories with students on topics ranging from his days of chaining himself to Boston University President John Silber’s fence in an act of protest, to how to win today’s climate change battle.

“There was a confluence when I was a student here of two big issues,” Mr. Abramowitz explained. “One was the fight of the freedom of Jews in the former Soviet Union. The other moral issue of the time, and perhaps the greatest moral issue of my generation, was apartheid in South Africa.”

Mr. Abramowitz and his fellow activists’ demands were clear: divestment of all university shares in companies that were profiting from the apartheid. The students organized rallies, made calls to other campuses urging for involvement, partook in hunger strikes, and even took over Mugar Library to spread their message.

“People in the university didn’t appreciate what we were doing,” Mr. Abramowitz explained. “They were like, “Well, what are you students really going to accomplish? What is this really going to do in the world?” Then what happened was Members of Congress started proposing sanctions legislation in response to this, like lots of Members of Congress.”

The Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 imposed sanctions on South Africa while outlining five preconditions for lifting said sanctions and ending apartheid. President Ronald Reagan vetoed the bill saying he favored “constructive engagement.” But then, Mr. Abramowitz explained, something tipped the scale.

“The only time Reagan’s veto was overturned was in his first term in office at the height of his popularity--it was on the sanctions against South Africa,” he said, smiling. “And that’s what students can do. I can’t say that when we were chaining ourselves to President Silber’s fence we were thinking about overturning Reagan’s veto, but just social movements--creating the wave and catching the wave, is really, really important.”

Mr. Abramowitz continues to ride the wave of activism today as CEO of Energiya Global Capital, a Jerusalem-based impact investment platform that provides returns to investors while furthering Israel’s environmentalism and advancing affordable green power to underserved populations as a fundamental human right. The organization was founded shortly after Mr. Abramowitz, his wife, Susan Silverman (CAS ‘85) and their five children moved over 5,000 miles across the globe from Newton, Massachusetts, to Kibbutz Ketura, Israel, in 2006.

“My family and I arrived to the Kibbutz right at sunset. We opened the air conditioned doors and boom we’re hit with this heat that was so disorienting,” Mr. Abramowitz explained. “The sun was just dipping and felt like superman laser beams going “woosh!” burning us to a crisp. At that point I had the thought, “Oh I’m sure the whole place works on solar power.””

Quickly, Mr. Abramowitz discovered that despite Israel being dubbed a “world leader” in solar technology, no one in the region was utilizing its power.

“The response I got was, “oh yeah, Israel’s a world leader in solar technology but no one’s crazy enough to take on the government,”” he explained. “Then I thought...the burden, privilege, and responsibility of rebellion…”

Mr. Abramowitz was crazy enough for the job. He teamed up with his business partners, Ed Hofland and David Rosenblatt, and together the three founded Arava Power Company. In 2011, the organization unveiled Israel’s first solar energy field at Ketura. Energiya Global Capital came next, with a goal of providing clean, sustainable solar energy for 50 million people by 2020.

“If someone could unlock the value, if someone can actually prove that it’s not out of reach, it's actually doable, if something could change the paradigm, why not us?” he asked. “Why not us?”

A question and answer session followed Mr. Abramowitz’s remarks. A BU senior inquired about his approach to successful activism.

“What were some things that kept you going or helped you succeed during your activism battles and efforts?” she asked.

“Know what your values are,” Mr. Abramowitz answered. “If you believe in them, do something about it. I was privileged to be gifted these very powerful values at a time when they lead to action and world change. I think that’s been lost in this generation because social media make it too easy to like or dislike and you feel like, “Okay, I’ve already weighed in.” You cannot forget about the action.”

To learn more about Mr. Abramowitz, his work, and his hopes for the next generation visit http://www.bu.edu/today/2014/civil-disobedience-a-love-story/.