My most prized possessions are books.

Though my computer is my most expensive possession, followed by my bed and my couch, I wouldn’t think twice about discarding all three items if I had to, say, move across the country or update my laptop for a job.

But my books, as inexpensive as they might be individually, collectively map my personal history from the University of Michigan to New York City to Boston. They tell the story of why I became an English teacher for three years after college, what brought me to law school, and who I have become in the process.

So, when I saw that Boston University, through the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center in the undergraduate library, sponsors an annual book collection contest for students, I was thrilled. Yesterday, I submitted my entry, which included an annotated bibliography of a specific group of my books, a statement describing how and why I acquired the books, and an essay discussing the collection’s unifying theme.

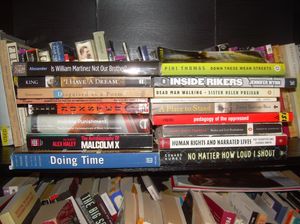

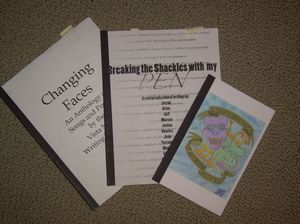

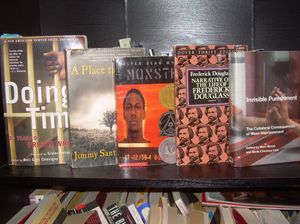

My collection, entitled Reading Between the Bars: Books By or About Incarcerated Americans, includes mainly books that I acquired while facilitating creative writing and theater workshops in Michigan detention facilities during college. Some of the books include factual information about our country’s criminal justice system and others consist of personal narratives of incarcerated individuals, some famous, like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. (who wrote Letter From a Birmingham Jail), and others relatively unknown, like Bruce and Charles, who participated in my writing workshops and whose original work appears in anthologies I created.

My essay focuses on the theme of liberation through literacy, exploring how several authors in my collection have broken free from personal or institutional shackles as a result of reading and writing. Most literally, perhaps, is the story of Frederick Douglass, who overheard his slave-master say, “Learning would spoil the best [slave] in the world . . . if you teacher that [slave] how to read, there would be no keeping him,” and thereafter “understood the pathway from slavery to freedom.”

Less known narratives include those of contemporary American prisoners who have also liberated themselves to varying degrees through literacy. Jimmy Santiago Baca, the author of multiple books in my collection, taught himself to read and write in prison after borrowing books on Chicano history and the Romantic poets. In the essay Coming Into Language, he chronicles his personal transformation:

“[W]hen at last I wrote my first words on the page, I felt an island rising beneath my feet like the back of a whale . . . I had a place to stand for the first time in my life. The island grew, with each page, into a continent inhabited by people I knew and mapped with the life I lived.”

After being released, Baca emerged as a prolific poet, winning awards such as the American Book Award and Pushcart Prize and leading writing workshops with incarcerated and marginalized populations across the country.

These stories, like those of the boys, girls, and men I wrote with in Michigan detention facilities, have the potential to change lives. I know from experience, because after reading and witnessing these stories first-hand, I decided to become an inner-city English teacher, committed to empowering Bronx students through reading and writing. Given almost free reign with my new curriculum, I naturally exposed my students to books dealing with incarceration, among others, including texts by Douglass, Baca, Martin Luther King, Jr., and my former workshop participants.

Even though students did not always listen to me, they could not as easily ignore the voices of those freed—figuratively or literally—by reading and writing. I sensed that what engaged students in these texts, in addition to this theme of liberation and the novelty of prison writing, is what stirred me while volunteering in Michigan detention facilities: the recognition that in even the most dismal and hopeless setting, in even the most despicable and hated individual, there is a kernel of hope, a measure of humanity, a potential for redemption.

As important as this message is for inner-city students, or anyone who has been pushed to the margins of society, I believe this message is also important for those of us training to be lawyers—those of us who would play a role in putting people behind bars, defending them, or working towards a fair and equitable criminal justice system for all.

If nothing else, my book collection reminds me of this message. It reminds me that between the lines in my books, between the bars in the American justice system, there are human lives and stories waiting to be heard.

2 Comments

dlinhart posted on March 30, 2011 at 3:00 pm

Wow, thank you for taking the time to share this story with images that will stick with me– it’s amazing to track down specific turning points for historical and contemporary giants like Douglass and Baca, and to find that these turning points are accessible to others and repeatable. There can be more giants. Right now I’m feeling motivated about what words can do for individuals, and then what those individuals can do for all of us.

William Xifaras posted on April 18, 2012 at 10:47 pm

Absolutely essential for future attorney’s (especially those in criminal law, regardless of what side) to understand the despair of the incarcerated.

Having spent 5 years in state prison for Intimidation, which resulted from a shooting, I experienced these conditions first hand. Some of my closest friends will never be coming home. Many have spent 25 to 35 years incarcerated. Two close friends of mine went in at 16 & 17 for murder charges. One just got out at age 47 and the other won’t ever be coming home (2 counts of first degree murder). All alleged gang/ mob stuff, but it was Italians killing other Italians, no blacks involved.

Although your theme seems to be around incarceration of African American prisoners, I can tell you the scenario is the same for whites and hispanics as well. Most of my white friends are doing 1st and 2nd degree murder charges with an average of 30 years incarceration.

Anyways, I appreciate your message and your wanting to let others in law understand what a great responsibility you all have regardless of which side of the law they are practicing.

@DoTime_WX