My wife finished her double Masters in social work and public health at BU last summer. In her last semester, she took a class on health law and got to taste the sweet nectar of legal analysis. When I think about “legal analysis” the first image that pops to mind is a 1L protesting a court holding with: “That’s not fair!” Professors live for these teachable moments: “Fairness is not a legal argument.”

It turns out that fairness is a last ditch appeal when you’ve run out of legal arguments—that is, favorable interpretations of existing law as applied to the facts of the case. In my 2L seminar on housing law, the professor actually had to prepare us on the first day for the culture shock of what we’d be talking about in that class: “I know you’re not used to it, but in this class we’ll be talking about things like fairness…” I’m not sure what happened after that because I immediately gathered my personal effects, walked out and washed my face with cold water—no, no, you know me, I was ready to drink those fairness conversations like a thirsty camel, which by the way “can drink as many as 30 gallons (135 liters) of water in about 13 minutes” according to National Geographic Camel Facts. Imagine having to share water with a camel on a long desert trek:

Camel: Can I get a sip of the water?

Lawyer: Not a chance bro.

Camel: But the water is for both of us. That’s not fair!

Lawyer: I have no idea what you’re talking about.

Given that my wife knows all about not-talking-about-fairness-unless-you-have-to after the health law class, it’s now my turn to taste the sweet nectar of sociological analysis. Whereas I couldn’t get through a 1L casebook without reading a J. Posner opinion, in Urban Poverty and Economic Development with BU School of Social Work Professor Cooney, I can’t get through a sociological study on the roots of poverty concentration without being referred to William Julius Wilson. Also, whereas lawyers recast the mental exercises of lawyers before us for our analysis, sociologists rely on a strange beast called “evidence” gleaned from census data and other surveys and interviews with live people.

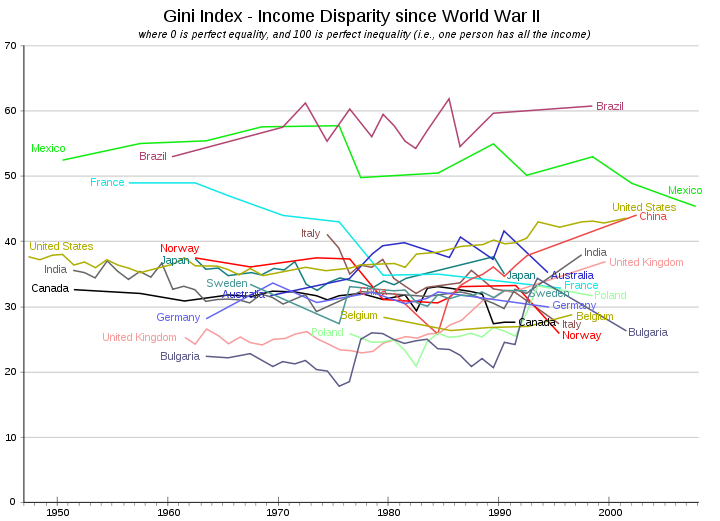

Our class looked at this graph of income disparity over time. What's with that bright blue line country?

William Julius Wilson’s take on poverty concentration is that the transition from an industrial to a technical and service-based economy, and from an urban to a suburban center of residential gravity, left inner city residents without low-skill, living-wage jobs. He wrote a book called When Work Disappears to provide the details. Those who got to play in the new economy had comfortable jobs, and those left out had no jobs. But the bigger story is the generational trajectory that is embarked upon by matching substantial income with sophisticated financial services. I wrote in Part 2 of this series that:

In some sense, two financial worlds are maintained. One runs on payroll, spending and savings. The other runs on leveraged investment, tax benefits and returns on investment. Across these two worlds, we’re not just talking about a spread in who can afford a transit pass vs. a used car vs. a luxury car. We’re talking about a spread in education, housing and health outcomes for whole families, as well as in the self-determined choices that the realities of life give us permission to make.

Income from any source gives us money, not financial security. In fact, I learned from my 2L Corporations class regarding the leveraged takeovers of KKR and others that dealmakers don’t even need their own money. In the world of deals, debt is participation. And saving money is like saving time. It connotes efficient allocation of the resource toward the goal, not holding onto something that slips through the hands. If you can spend money in a way that earns more of it back than you spent, then others will give you their money to spend. Even when some investments go sour, the hard-to-pin-down skill of getting return on investment (ROI) flowing means that credit will never fully dry up for you.

It may be that one of the most pragmatic life skills to learn in the society we have, for better or worse, is how to invest money. Then we can begin to command resources and attention to achieve self-determined goals, enlarging the concept of returns beyond just making more money to include fair, evidence-based social change.

2 Comments

Yaminette posted on February 22, 2012 at 2:38 pm

What a wonderful merge of the different perspectives you are learning on wealth and poverty! Also, the camel bit was absolutely hilarious!

mike posted on February 28, 2012 at 12:35 am

dude, that was awesome.