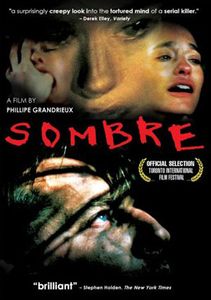

Verite camerawork has been a major force in the modern horror film, but to mixed success at best. I always hoped that somewhere out there, someone had gotten it right. That someone was Philippe Grandrieux. He did it back in 1998, a year before Blair Witch made the technique into a style, with his film Sombre. To be fair, I can only call it a horror film because it certainly isn’t anything else, and I guess it does fit best into that genre. There are no people jumping out of the darkness and there is no gore, but there is an all-enveloping sense of doom that permeates every single frame. What separates the film from others of the type is that Grandrieux doesn’t create his mood through the disorientation inherent to handheld camerawork, but instead through lighting and focus. The title is, in a way, kind of a joke as “somber” barely even begins to describe this work, but I guess Misery was already taken and “sombre” also translates to “darkness,” which fits perfectly. This is a dark film in every sense of the word and even many of the film’s brightest shots are out of focus, as if the director wants to call the audience into the prevailing darkness. This lack of light does something vital to the film as a whole. It takes people and objects and turns them into abstract forms on a means eerily reminiscent of Brakhage. Grandrieux appears to have a rare talent for pulling something vital out of every image in his film. All those vital little images come together to form one of the greatest horror films of all time.

Verite camerawork has been a major force in the modern horror film, but to mixed success at best. I always hoped that somewhere out there, someone had gotten it right. That someone was Philippe Grandrieux. He did it back in 1998, a year before Blair Witch made the technique into a style, with his film Sombre. To be fair, I can only call it a horror film because it certainly isn’t anything else, and I guess it does fit best into that genre. There are no people jumping out of the darkness and there is no gore, but there is an all-enveloping sense of doom that permeates every single frame. What separates the film from others of the type is that Grandrieux doesn’t create his mood through the disorientation inherent to handheld camerawork, but instead through lighting and focus. The title is, in a way, kind of a joke as “somber” barely even begins to describe this work, but I guess Misery was already taken and “sombre” also translates to “darkness,” which fits perfectly. This is a dark film in every sense of the word and even many of the film’s brightest shots are out of focus, as if the director wants to call the audience into the prevailing darkness. This lack of light does something vital to the film as a whole. It takes people and objects and turns them into abstract forms on a means eerily reminiscent of Brakhage. Grandrieux appears to have a rare talent for pulling something vital out of every image in his film. All those vital little images come together to form one of the greatest horror films of all time.

In the beginning, a car drives through a valley, setting up the film’s obsession with shadows and showcasing some of the more beautiful imagery. We then see some schoolchildren watching a show of some sort and shrieking at the stage. A man, Jean (Marc Barbe), comes out of the darkness. He wanders around the countryside, occasionally stopping to watch the Tour De France and kill a prostitute. He begins to sleep with them, but then blindfolds and strangles his victims as part of his routine. After half an hour of this, he meets two sisters who couldn’t be more different, Claire (Elina Lowensohn), a dark, brunette, short and moody virgin, and Christine (Geraldine Voillat), who is her sister’s opposite in nearly every way—she is blonde, tall, pale and reasonably happy and overtly sexual. There is something deeply allegorical about this relationship and how their roles shift over time. They travel together, even if it isn’t totally clear why. They drive around for a while before Jean’s urges take over. He tries to fill them at a club, but that doesn’t seem to work. They stop for a swim, and he tries to rape and kill Christine, but Claire stops him and tries to get away. He catches them, ties Christine up and takes Claire to a club. From here, things shift in ways you wouldn’t expect, and the film begins to ask if Jean can be redeemed by pure love alone. Or maybe it’s asking if anyone can, or if it’s even worth trying.

“Mood” is a word you hear about a lot today in film discussion. It is generally used to describe the masters of Hong Kong’s art film circuit and their contemporaries throughout southeast Asia: Wong Kar Wai, Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Tsai Ming Liang and Apichatpong Weerasethakul. Some Europeans are occasionally mentioned with them, maybe Clair Denis and Bela Tarr, but from this film alone it becomes clear that Grandrieux belongs to that group. There’s an obvious reason why he must labor in relative obscurity as the others enjoy international success: the other directors I’ve listed (with the possible exception of Tarr, whose fame comes for other reasons entirely) create mood out of emotions that we can all comprehend. Even the sadness and loneliness in the work of the other great filmmakers comes packaged in beautiful poetic lyricism. Sombre is still a beautiful film, but that beauty comes packaged in suffocating misery and darkness. Whatever plot there may be doesn’t make total sense, and as much happens between frames as within the film itself, but that doesn’t matter because Sombre is more than that. It achieves what most worthwhile film set out to achieve: it is a constant succession of near-perfect images. Sure, the film’s soundtrack is significant, as Grandrieux makes great use of ambient noises and expressive music, including goth-rock pioneers Bauhaus, but it never becomes central to a scene. The performances are all pretty great as well, especially Barbe, but it is in no way a performance piece. It expresses interesting ideas in regards to redemption, humanity, love and morality, especially in the connection between redemption and love, but these ideas aren’t what makes this an important film. That falls to the imagery. That beautiful, overpowering darkness. That perfect motion in and out of light. Grandrieux has crafted the perfect horror film because he knows exactly how one must move the camera, and exactly what should be allowed in front of it. Since the film ended, I have been racking my brain in a search for a better horror film, but unless I stretched the limits of what constitutes horror beyond what I think is right, I just can’t think of one. This may truly be the masterpiece of the genre as a whole. Needless to say, as it will only be in town for one showing as part of an HFA retrospective on Grandrieux, I can’t even begin to say how much I encourage you to go. Films like this just don’t come around often enough.

-Adam Burnstine

Sombre is not rated. Needless to say, I probably wouldn’t bring kids to see it.

It will be showing on Friday, February 26th at 7:00 at the Harvard Film Archive with Grandrieux appearing in person. On Saturday, he will be presenting his latest film, Un Lac.

Directed by Philippe Grandrieux; written by Philippe Grandrieux, Sophie Fillieres and Pierre Hodgson; cinematography by Sabine Lancelin; edited by Francoise Tourmen; production designer, Gerbaux; original music by Alan Vega; produced by Catherine Jaques. Running time: 1 hour, 57 minutes.

With: Marc Barbe (Jean), Elina Lowensohn (Claire) and Geraldine Voillat (Christine).