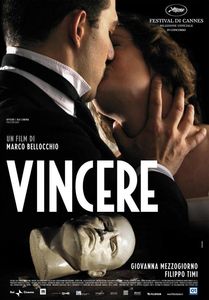

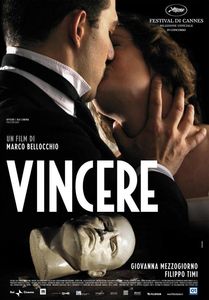

I first fell in love with the work of Marco Bellocchio after viewing I pugni in tasca (Fists in the Pocket, 1965), a masterpiece of Italian cinema that perfectly captured the psychological disturbances of its characters. My fondness for the director’s work was reignited after his 2003 drama Buongiorno, Notte (Good Morning, Night), which also beautifully presented the turbulent states of mind of the main characters. Needless to say, I had high expectations for Bellocchio’s most recent work, Vincere, which followed the tragic life of Ida Dalser, the first and secret wife of Benito Mussolini. Hoping to see the same in-depth (almost frightening) psychological analyses of the film’s historical characters, I was disappointed in the lack of character development, as well as the confusing plot structure. Despite the efforts of Giovanna Mezzogiorno, who plays Ida, the performance falls short of expectations, as Ida is portrayed as a psychologically two-dimensional and co-dependent woman, merely obsessed with her idol, rather than a victim of Mussolini, as was supposedly intended.

I first fell in love with the work of Marco Bellocchio after viewing I pugni in tasca (Fists in the Pocket, 1965), a masterpiece of Italian cinema that perfectly captured the psychological disturbances of its characters. My fondness for the director’s work was reignited after his 2003 drama Buongiorno, Notte (Good Morning, Night), which also beautifully presented the turbulent states of mind of the main characters. Needless to say, I had high expectations for Bellocchio’s most recent work, Vincere, which followed the tragic life of Ida Dalser, the first and secret wife of Benito Mussolini. Hoping to see the same in-depth (almost frightening) psychological analyses of the film’s historical characters, I was disappointed in the lack of character development, as well as the confusing plot structure. Despite the efforts of Giovanna Mezzogiorno, who plays Ida, the performance falls short of expectations, as Ida is portrayed as a psychologically two-dimensional and co-dependent woman, merely obsessed with her idol, rather than a victim of Mussolini, as was supposedly intended.

The film’s powerful beginning—a young Mussolini (Filippo Timi) challenging God to strike him dead within five minutes to prove His existence—immediately captures interest and curiosity. We are introduced to Mussolini (before his rise to power), who captivates Ida Dalser with his political beliefs and charisma. The film jumps between two moments that occur years apart: Ida’s first and brief encounter with Mussolini, and their reunion. The two fall passionately in love, just as World War I erupts. Ida proves her love for the emotionally-distant Mussolini by selling her home, business, and belongings to fund his newspaper. Over time, Ida has a son, named Benito Albino, whom Mussolini recognizes. However, after leaving to fight in the war, Mussolini abandons Ida and the young Benito for Rachele Guidi (Michela Cescon), whom he eventually marries. Ida, understandably outraged, writes letters to any and every authority (including the Pope), claiming to be Mussolini’s true wife, but to no avail. As Mussolini rises to power, Ida and Benito Albino are first placed under strict surveillance and later separated, with Ida being placed in an asylum and the young Benito being sent to a boarding school.

Despite Mussolini’s denial of their marriage (and of course he then denies that he is the father of Benito Albino), Ida continues to write to the authorities, claiming that Benito Albino is Mussolini’s true heir. After years of torture and imprisonment, Ida has the opportunity to be released if she admits that she is not the wife of Mussolini. Although very little screen time is devoted to the young Benito Albino, he does receive some attention as a young man. In a powerful scene, a college-aged Benito (also played by Filippo Timi) presents a compelling impersonation of his father for his mates. The impersonation proves the resemblance between father and son (after all, children are always the best at impersonating their parents), but also shows the psychological state of a young man after years of isolation. The film’s conclusion is as strong as its beginning, though I must warn you, it is not uplifting.

While the story of a dictator’s secret wife and child is—I would argue—inherently interesting, Vincere’s plot is sometimes confusing, as Bellocchio jumps around temporally and often assumes that the audience is familiar with the life of Il Duce. That being said, Vincere is by no means a history lesson of the life and career of Mussolini or of a fascist Italy. After Mussolini abandons Ida and his son, very little screen time is given to the dictator other than brief scenes and some archival footage of the real Mussolini. Although this absence of Mussolini establishes Ida as the main character of the film, it becomes difficult to discern Ida’s relationship to Mussolini both during and after his rise to power. Also, characters’ names and titles are often unclear. We do not learn of Ida’s name until well into the film, as she sells her possessions for Mussolini’s newspaper, and several government officials are inserted into the film without explanation.

Most important, the proof of Ida’s marriage to Mussolini is extremely ambiguous. A wedding scene between Ida and Mussolini is depicted late in the film (Ida is already institutionalized and her sanity questioned), but could this be a dream or a flashback? Also, Ida claims that government officials ransacked her home on Mussolini’s command, stealing all of her documents, and therefore she cannot produce a marriage certificate. However, several characters suggest that the very document that could prove Ida’s truthfulness and save her and her son is tucked away in a known hiding place within the home, leading me to wonder why they did not simply present the marriage certificate and save Ida. Could this ambiguity be the result of a plot hole or merely a matter of translation?

However, there are also several aspects of the film that deserve recognition. The rapid Eisensteinian editing of archival footage of Mussolini’s rise to power and Italy’s role in both World Wars is particularly interesting, capturing the political fervor of the population, as well as the vulnerable state of the nation. However, it must be said that the lack of resemblance between Filippo Timi and the real Mussolini can potentially be confusing to those unfamiliar with Il Duce’s appearance. Many scenes are beautifully shot, often using chiaroscuro lighting (particularly in the opening scenes). A particularly beautiful image occurs late in the film, with Ida imprisoned within the dark asylum, yet a window to the outside world shows a beautiful Christmas Eve’s snowfall. Such shots almost allow for us to forgive the film of any faults…almost.

The confusing plot structure and ambiguities detract from Ida’s character. Rather than a woman victimized and ruined by Mussolini, Ida often seems unnaturally obsessed with the dictator, idolizing him as a teenage girl might obsess over a Hollywood heart-throb. To be clear, I am not justifying Mussolini’s treatment of Ida. However, throughout much of the film I found myself wanting to tell Ida to move on with her life without Mussolini. Because of her obsession with Il Duce, it is difficult to discern Ida’s sanity, and, as a result, she does not have our complete sympathy.

Overall, Bellocchio’s Vincere is thought-provoking and beautiful to watch. While it does not capture my affection as his earlier works, it definitely provides us with something to talk about. I personally appreciated how the film refrained from judging Mussolini politically, therefore avoiding a preachy tone. Rather, it focused on the dictator’s treatment of Ida, allowing us a glimpse into a little-known aspect of Mussolini’s history. Finally, while it may have fallen short of my (high) expectations, Vincere nevertheless reminded me of why I love the work of Bellocchio in the first place and encouraged me to re-view those films that sparked my appreciation of this gifted director several years ago.

-Melissa Cleary

Vincere opens at the Landmark Kendall Square Theater on March 26, 2010 and is not rated.

Directed by Marco Bellocchio; story by Marco Bellocchio; screenplay by Marco Bellocchio and Daniela Ceselli; director of photography, Daniele Cipri; edited by Francesca Calvelli; original music by Carlo Crivelli; production designer, Marco Dentici; produced by Christian Baute, Mario Gianani, Hengameh Panahi, and Olivia Sleiter; released by IFC. Running time: 122 minutes.

With: Giovanna Mezzogiorno (Ida), Filippo Timi (Mussolini and Benito Albino), Corrado Invernizzi (Dr. Cappelletti), Fausto Russo Alesi (Riccardo), and Michela Cescon (Rachele).

Norman Jewison’s 1987 film Moonstruck, a landmark romantic comedy, is positively bursting with insight on matters of love and marriage in the modern world. At its core, the movie makes two central assertions about the mysteries of the human heart. First, that love and happiness are dependent almost entirely on luck; and second, that men cheat on their wives because they fear death. The film’s grand finale considers both.

Norman Jewison’s 1987 film Moonstruck, a landmark romantic comedy, is positively bursting with insight on matters of love and marriage in the modern world. At its core, the movie makes two central assertions about the mysteries of the human heart. First, that love and happiness are dependent almost entirely on luck; and second, that men cheat on their wives because they fear death. The film’s grand finale considers both. I first fell in love with the work of Marco Bellocchio after viewing I pugni in tasca (Fists in the Pocket, 1965), a masterpiece of Italian cinema that perfectly captured the psychological disturbances of its characters. My fondness for the director’s work was reignited after his 2003 drama Buongiorno, Notte (Good Morning, Night), which also beautifully presented the turbulent states of mind of the main characters. Needless to say, I had high expectations for Bellocchio’s most recent work, Vincere, which followed the tragic life of Ida Dalser, the first and secret wife of Benito Mussolini. Hoping to see the same in-depth (almost frightening) psychological analyses of the film’s historical characters, I was disappointed in the lack of character development, as well as the confusing plot structure. Despite the efforts of Giovanna Mezzogiorno, who plays Ida, the performance falls short of expectations, as Ida is portrayed as a psychologically two-dimensional and co-dependent woman, merely obsessed with her idol, rather than a victim of Mussolini, as was supposedly intended.

I first fell in love with the work of Marco Bellocchio after viewing I pugni in tasca (Fists in the Pocket, 1965), a masterpiece of Italian cinema that perfectly captured the psychological disturbances of its characters. My fondness for the director’s work was reignited after his 2003 drama Buongiorno, Notte (Good Morning, Night), which also beautifully presented the turbulent states of mind of the main characters. Needless to say, I had high expectations for Bellocchio’s most recent work, Vincere, which followed the tragic life of Ida Dalser, the first and secret wife of Benito Mussolini. Hoping to see the same in-depth (almost frightening) psychological analyses of the film’s historical characters, I was disappointed in the lack of character development, as well as the confusing plot structure. Despite the efforts of Giovanna Mezzogiorno, who plays Ida, the performance falls short of expectations, as Ida is portrayed as a psychologically two-dimensional and co-dependent woman, merely obsessed with her idol, rather than a victim of Mussolini, as was supposedly intended. In recent years, timeliness has been high on the minds of most box office prognosticators. Last winter, some blamed the box office disappointments of films like The International and Confessions Of A Shopaholic on how they related to current events. The International was deemed too timely with its story of evil bankers trying to take over the world coming just months after the bank-fueled collapse of Wall Street. On the other hand, Confessions was widely criticized for its pre-recession notions of spending as a way of life. Of course, I’d like to think that both disappointed due to the simple fact that they were bad films, but if I’m wrong, then it doesn’t speak well to the box office chances of Miguel Sapochnik’s debut feature Repo Men, a film that portrays the business side of medicine as so evil that it may as well have been funded by the Obama administration. On the other hand, it may fail because, once again, it simply is not a good film. In fact, for large portions of its runtime, it is a spectacularly awful one, although it eventually rises above this to become simply bad.

In recent years, timeliness has been high on the minds of most box office prognosticators. Last winter, some blamed the box office disappointments of films like The International and Confessions Of A Shopaholic on how they related to current events. The International was deemed too timely with its story of evil bankers trying to take over the world coming just months after the bank-fueled collapse of Wall Street. On the other hand, Confessions was widely criticized for its pre-recession notions of spending as a way of life. Of course, I’d like to think that both disappointed due to the simple fact that they were bad films, but if I’m wrong, then it doesn’t speak well to the box office chances of Miguel Sapochnik’s debut feature Repo Men, a film that portrays the business side of medicine as so evil that it may as well have been funded by the Obama administration. On the other hand, it may fail because, once again, it simply is not a good film. In fact, for large portions of its runtime, it is a spectacularly awful one, although it eventually rises above this to become simply bad. Since taking his first foray into seriousness with Annie Hall in 1977, Woody Allen has been nothing if not upsetting, morally and emotionally. His earliest films were one laugh riot after another—ingenious, cheeky, odd—but he really hit his stride when he embraced his inner Ingmar Bergman in the late 1970s and beyond, asking the Big Questions with an uncommon, mature solemnity. Manhattan surveyed the emotional wreckage of a man whose wife left him for another woman. Crimes and Misdemeanors implied that murder was an acceptable solution to a mistress problem. Match Point argued that morality is meaningless in a world dominated by luck and happenstance.

Since taking his first foray into seriousness with Annie Hall in 1977, Woody Allen has been nothing if not upsetting, morally and emotionally. His earliest films were one laugh riot after another—ingenious, cheeky, odd—but he really hit his stride when he embraced his inner Ingmar Bergman in the late 1970s and beyond, asking the Big Questions with an uncommon, mature solemnity. Manhattan surveyed the emotional wreckage of a man whose wife left him for another woman. Crimes and Misdemeanors implied that murder was an acceptable solution to a mistress problem. Match Point argued that morality is meaningless in a world dominated by luck and happenstance. If you plan to see J’ai tue' ma mere with the hopes of seeing a film about matricide, you will be disappointed. The protagonist does not kill his mother, physically at least. But Xavier Dolan’s directorial debut, J’ai tue' ma mere, has won international attention and for plenty of reasons. The plot may not be the most original—a teenage boy has a strained relationship with his mother—but the powerful performances of Dolan and Anne Dorval, combined with the intensely colorful and artistic images interspersed throughout the film linger in the mind long after the film has ended.

If you plan to see J’ai tue' ma mere with the hopes of seeing a film about matricide, you will be disappointed. The protagonist does not kill his mother, physically at least. But Xavier Dolan’s directorial debut, J’ai tue' ma mere, has won international attention and for plenty of reasons. The plot may not be the most original—a teenage boy has a strained relationship with his mother—but the powerful performances of Dolan and Anne Dorval, combined with the intensely colorful and artistic images interspersed throughout the film linger in the mind long after the film has ended.