The kestrel is a spectacular bird, known for its tendency to hunt by flying into the wind at windspeed, resulting in a unique kind of hovering called “wind-hovering”. While it is not a true hover, which is achievable only by insects and hummingbirds, it is an effective hover with respect to the ground, and gives the bird an edge in finding prey in flight.

The American kestrel. More colorful than the common kestrel. Photo (c) J. B. Churchill

Wind-hovering while hunting has been shown to be extremely effective, resulting in 2.82 prey caught an hour, as opposed to 0.21 when perching, 0.31 when soaring, and a measly 0.07 when sitting. The kestrel wind-hovers in bouts of about 25 seconds, after which it either strikes against its prey or breaks the wind-hover and finds a new position to hunt, where it reestablishes a wind-hover. During its lack of motion relative to the ground, the kestrel looks downward and keeps its head remarkably still. This is imperative to the kestrel’s hunting, as any movement of the head disrupts its vision and makes it unable to see its targets.The importance of the stability of the kestrel’s head results in a new element being required in its flight: intermittent bursts of gliding and flapping.

Ideally, a method of hunting should require a minimum amount of energy and yield a maximum amount of food. Hunting while wind-hovering has already been shown to have a very high food yield, but gliding , which would be ideal in terms of its requirement of energy, results in a downward velocity of the bird, disrupting the glide and the stability of the kestrel’s head. With its astounding neck flexibility, the kestrel is able to glide and keep its head fixed while allowing its center of gravity to sink for a short amount of time, but the bird will eventually no longer be able to stretch and its vision will be disrupted, compromising its hunt. Constant flapping flight would solve this problem, but it requires a great deal of energy, making it an impractical method of hunting. The kestrel therefore finds a happy medium: intermittent bouts of gliding and flapping.

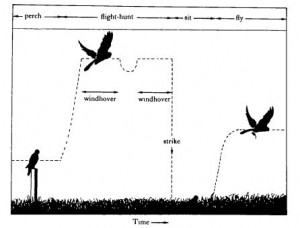

Hunting behavior of kestrel.

The kestrel enters a glide as it begins its wind-hovering hunt. It then maintains this glide for as long as its neck flexibility will allow without its head stability being disrupted, about 25 seconds. It is then required to flap several times, returning its center of gravity to its initial position close to its head. The kestrel does not always immediately reestablish a wind-hover, but sometimes strikes against its prey at the end of the 25 second period. This may explain why the kestrel wind-hovers in 25 second bursts.

Kestrels are some of the most successful birds of prey, occupying all parts of the world with the exception of Antarctica, the tundras, and deserts. Their remarkable manipulation of the elements to aid their survival no doubt contributes to their resounding success.

Sources:

- Photo of the American kestrel, by J. B. Churchill

- Intermittent Gliding in the Hunting Flight of the Kestrel

- The Raptor Foundation

- The Cornell Lab of Ornithology

One Comment

Lorena Barba posted on December 12, 2011 at 10:39 pm

Nice post. Very beautiful bird indeed!

(I added a note to the copyright holder of the photograph of the American Kestrel, as it is not public-domain.)