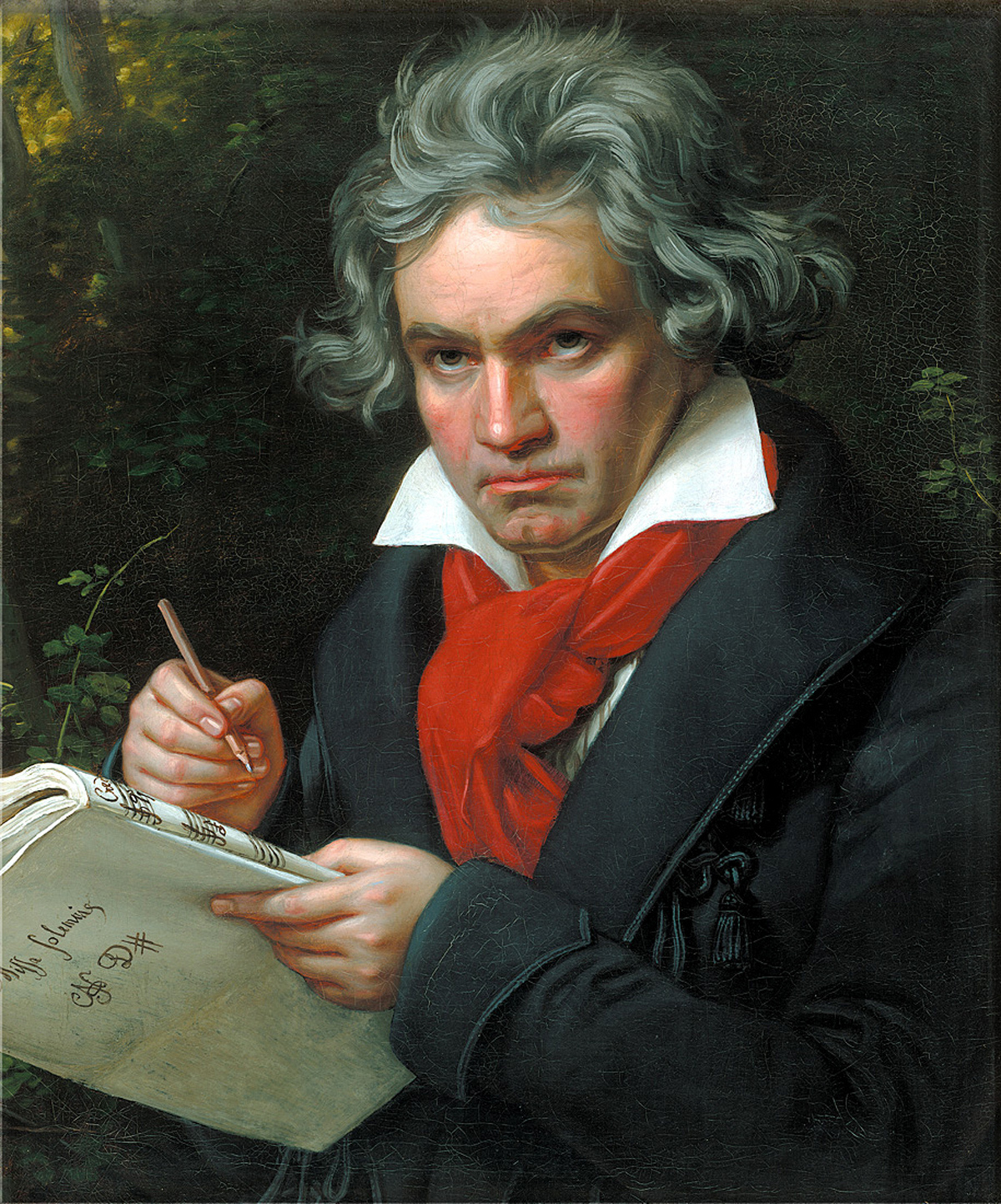

A depiction by Achille Devaria of Voltaire greeting Ben Franklin and his nephew as they visit France.

—© DeA Picture Library / Art Resource, NY

CC202 has just moved on from Candide. Voltaire strikes even the casual reader as a captivating persona, with wit and intelligence.

However, Voltaire's role in the "Republic of Letters" is certainly worth a mention. To escape arrest, Voltaire lived at Cirey for fifteen years. He wrote a steady stream of letters to stay connected with his friends in Paris and others who were abroad, which helped promote his plays, historical works, and essays, while keeping him up to date with the latest intellectual developments.

This recent article from the National Endowment for the Humanities tells us more:

“Republic of Letters” sounds like a term coined by a historian, but it was one used by the participants themselves. In an era defined by monarchical government, class hierarchy, and religious divisions, the members of the “republic” saw themselves as engaging each other on intellectual—and therefore equal—terms. “Letters” refers to both learning and the way that intellectual and scholarly developments spread throughout Europe and abroad. In thousands upon thousands of letters, members tried out new theories, critiqued ideas, relayed the newest gossip, and chronicled the mundane matters of life. The more international your network, the more cosmopolitan you were thought to be.

Correspondence was such an integral part of scholarly life that Montesquieu mocked it in his Persian Letters, when he has a boorish astronomer brag, “I have very little contact with people, and among those I do see, there are none that I know. But there is a man in Stockholm, another in Leipzig, and another in London, whom I have never seen, and no doubt shall never see, that I maintain such a regular correspondence that I never fail to write each of them with every mail.”

Scholars have used these letters to trace networks of friendships and shared knowledge. Who wrote to whom? Where did that idea come from? Did the English influence the French? Or, mon dieu, did the French influence the English? What about the Dutch? Have you heard the latest about Voltaire and his endorsement of Newton?

Much like our late-night Facebook chats or Skype calls with our old friends, these letters document how people at that time stay abreast of the trends and news of their time.

Working with the Packard Humanities Institute and the Electronic Enlightenment Project, the Stanford team created a database that logged the metadata for each letter, including sender, recipient, date, and location. A team of students led by Jeffrey Heer, then an assistant professor at Stanford, designed the visualization software. The tool, RPLVIZ, lets users select which authors to display, along with options to render the full correspondence, or only letters sent or received.

The resulting maps not only proved that correspondence could be visualized in a useful way, but also yielded surprising results. “Most of the correspondence networks were far more national than you would gather from reading the letters,” says Edelstein. Voltaire’s network explodes like a firework over France, with tails to England, Russia, and the Swiss cantons. John Locke’s covers England and Scotland, with a foray to Dublin. Correspondence by Joseph Addison, who founded The Spectator, sprawls from London to Dublin, Paris, Chennai, and Venice.

It is not surprising to see these spheres spread to the newly-formed United States of America.

If Voltaire left an indelible mark on eighteenth-century France, then the same can be said of Benjamin Franklin and America. Before Franklin became one of the Founding Fathers, he made a name for himself in Philadelphia as a publisher and innovator. In 1727, at the age of twenty-one, he formed “Junto,” a group of tradesmen and artisans who gathered to discuss key issues of the day. Four years later, he came up with the idea of creating a subscription library, which made it possible for members to read and share books they might not otherwise be able to afford. He also founded the Academy and College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania), becoming its first president in 1749. Along with running his own printing business, Franklin also served as the publisher of the Pennsylvania Gazette. When he wasn’t moving type and discussing politics, Franklin conducted scientific experiments, inventing the Franklin stove (a metal-lined fireplace) and bifocal glasses, not to mention his famous proposal of flying a kite with a key during an electrical storm to prove that lightning is electricity.

If the Republic of Letters was an imagined community of Western thinkers, then Franklin was certainly a member. But as a resident of Philadelphia, which had a population of 25,000 in 1750, Franklin didn’t have the same resources as someone who lived in a European capital. Paris had 565,000 residents, while London was bursting with 700,000. There’s also the matter of the Atlantic Ocean, which presented a vast physical obstacle to connecting with his European counterparts.

Perhaps, this "Republic of Letters" has evolved into Tweets and vlogs, and Snapchats. Do you see our communication as a natural successor to what happened in Voltaire's time? Leave a comment and let us know!

This month, EnCore book club attendees struggled with Erwin Schrodinger’s slim volume, What is Life?, a book that, as quoted in Goodreads, was “written for the layman, but proved to be one of the spurs to the birth of molecular biology and the subsequent discovery of DNA.”

This month, EnCore book club attendees struggled with Erwin Schrodinger’s slim volume, What is Life?, a book that, as quoted in Goodreads, was “written for the layman, but proved to be one of the spurs to the birth of molecular biology and the subsequent discovery of DNA.”

Professor Frederick Wasserman

Professor Frederick Wasserman Professor Jelle Atema

Professor Jelle Atema