By Anto Rondón

Ever since I read Simone De Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, I have considered myself a Feminist. This has never been a problem, not for me nor for those close to me. My parents celebrate it, my siblings do so too, my friends also, but there are some who share with me their criticisms for the movement, expecting to hear from me an argument that would convince them otherwise. The one criticism I tend to get is this: “Why is it called Feminism if it is a movement about Equality?”

In the following text, I will briefly explain to you why I think it should be called Feminism, and not something else, perhaps Egalitarianism. It is quite simple, but I will also draw it so it can be understood fully.

Feminism is defined, “a movement or theory supporting women’s rights on the grounds of equality of the sexes” (Oxford American Dictionary), that is, a movement grounded on the idea—or truth—that women are equal to men, and thus, deserve having equal opportunities. When it first arose, around the 1920s in Europe, the movement aspired to achieve a milestone: to allow women to vote. It succeeded (the Suffragette movement in England), and made it clear that women could hope to participate more in social and political life. Back then, this meant breaking many stigmas and eliminating many boundaries that limited women to the household and forced them to obey the superior sex: men. Gradually, this dream or hope became present in many works of literature and art in the voices of women—and some men—who understood that Feminism did not mean establishing a Matriarchy or supporting the supremacy of the female gender. It only meant raising the female gender to the level in which the male gender already was. It was not about limiting male rights, but about giving females the same rights, too.

Those were the ideas that had been presented by many, including De Beauvoir and Hannah Arendt in the 20thcentury, and even Mary Wollstonecraft, back in the 18th: that women were able to be as good as men in politics, science, art, and any other academic or practical area in the world; that they should be allowed to prove this, and that this did not threaten men; that including women would help all fields with different insights, opinions, and an influx of great minds.

It would also become very clear that Feminism was not a female only movement. Men should be involved because it is the image of their mothers, their wives, their partners, their female friends, and their daughters they would be fighting for. Accordingly, Feminism could only work if Education in the household, and in Universities and Schools celebrated the participation of women, too, and understood that the only difference between men and women was physical, not intellectual or practical.

This is Feminism, and it has been so since it emerged in the 1920s; even when nowadays, there are different waves with different objectives—some, perhaps, more valid than others—that sometimes do not fully resemble what Feminism used to be.

The thing is… Feminism’s goal is that men and women get to enjoy the same opportunities and privileges. But this does not mean it should be called Egalitarianism, “belief in or based on the principle that all people are equal and deserve equal rights and opportunities” (Idem). And the reason why is the following:

The female gender must ascend for there to be equality.

When the first Feminists visualized what they hoped to achieve, they would see the mold, the scaffold that already existed: the privileges and opportunities that men already enjoyed. They saw that men stood in an elevated position, and dreamed of reaching that position.

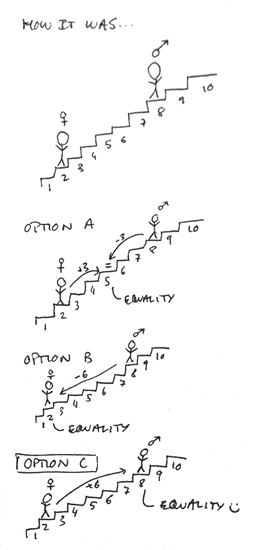

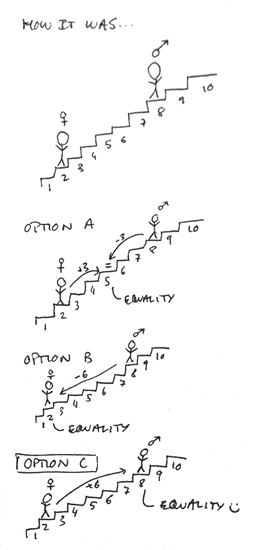

Let’s imagine a staircase of ten steps. The first Feminists realized that men stood in the eighth step, and that women were in the second step. There were only three ways to obtain equality.

Let’s imagine a staircase of ten steps. The first Feminists realized that men stood in the eighth step, and that women were in the second step. There were only three ways to obtain equality.

Option A: the female gender is elevated three steps, and the male gender goes down three steps. The problem with this is that in attaining equality, the male gender should not have to suffer any loss.

Option B: the male gender goes down six steps, and equality is achieved with both at the second step. Again, there must be a better way for the two genders to be equal, without one of them having to decay.

There is!—Option C: the female gender is elevated six steps and the male gender stays in the eighth step. Equality is achieved in step eight of the staircase.

In this scenario, women win privileges and opportunities they did not enjoy before, and men maintain the position they have always had. It is a win-win outcome, and equality is reached.

That is why it is called Feminism, because it is about elevating the female gender so it reaches the male gender. It is not about going further than that and establishing a Matriarchy, it is about achieving equality of the two genders. That is why it should be called Feminism, because it is about the hopes and dreams of women that aspire to be able to become anything they want to. It is about raising the female gender so it accompanies the male gender in step 8, or 10, or 100. After all, it is humankind, not mankind.

Images: Anto Rondón

Let’s imagine a staircase of ten steps. The first Feminists realized that men stood in the eighth step, and that women were in the second step. There were only three ways to obtain equality.

Let’s imagine a staircase of ten steps. The first Feminists realized that men stood in the eighth step, and that women were in the second step. There were only three ways to obtain equality.