It's that time of month. Tonight, EnCore-sters met to discuss Nathaniel Hawthorne's novel, The House of THE Seven Gables. One of the club attendees, the lovely Kim Santo, took great issue with one nefarious, print-on-demand copy of the novel present at the meeting that clearly lacked the necessary article on the volume title (I'll let you guess who brought that copy to the meeting). To make up for that frightening book's omission, all references to the "THE" will now be capitalized.

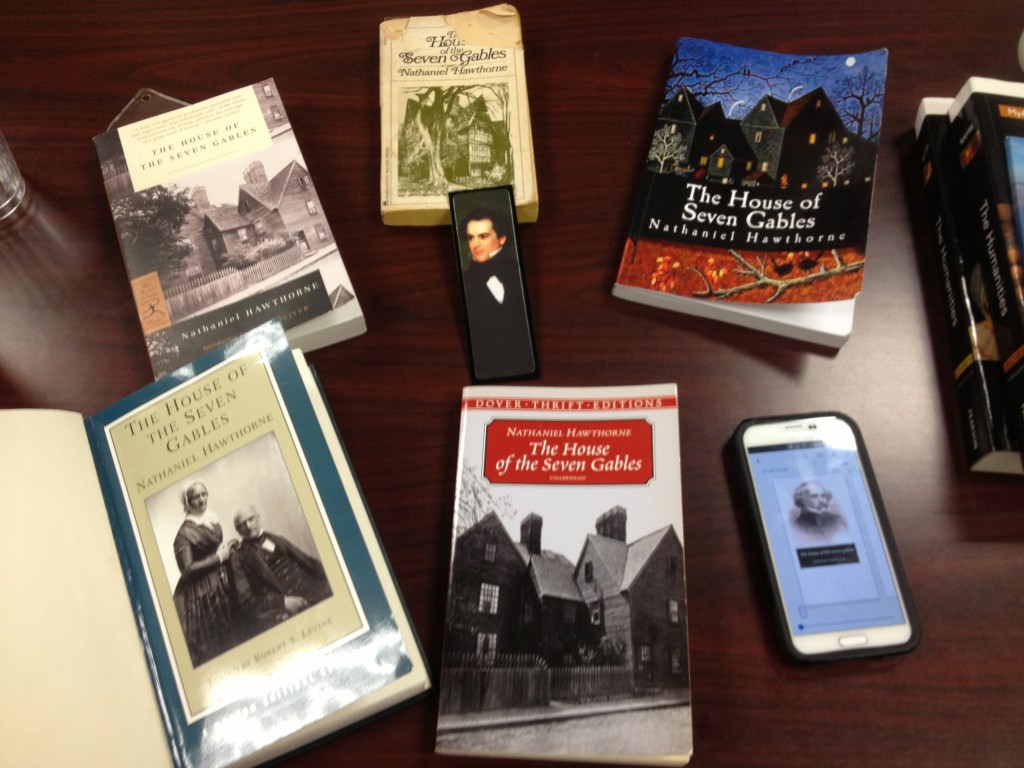

Pooling our copies

The novel follows a few generations of two New England families, the Pyncheons and the Maules, detailing their blood-soaked history and insinuating the presence of a curse laid on the Pyncheons and their stagnant, stately home. Is Hawthorne's novel unduly ignored in current book currents, shunted to the shadows of its more popular cousin The Scarlet Letter? Or is it a rightfully ignored, repetitious, impish rapier-thrust at colonial America's values and the centuries of social battle engendered from our forefathers? Can we trust this mischievous narrator? And is Kim slightly crazy for wishing she could purchase and live in the House of THE Seven Gables?

All of these questions were explored, as we nommed Bertucci's pizza (much love of sporkie was expressed at the outset of dinner) and drank copious amounts of red wine. We also dissected the very important topic of Hawthorne's perceived hotness or, to use the technical term, "foxy-ness."

From the start of the novel, we are treated to repetitious and heavy-handed descriptions of character features, and there was disagreement as to the necessity of this bloated prose. Do we NEED to hear 500 different times how a character's scowl does not reflect her true nature, or how a man's smile can be so sunny and "sultry" it dries the dirt in the road? While different readers had different reactions to the narrator's florid and overgrown language, it led to the important topic of Hawthorne's attitude towards puritanism, the aristocracy, and plebeianism. No one is (figuratively) left standing by the end of the novel.

When you stare into the void of Hawthorne's foxy eyes...does the void stare back?

One reader ventured that Hawthorne equally mocked all social classes, being the literary maverick that he was. Another pointed out that the playful mockery in the text was not just directed at political and social targets. Hawthorne goofs around with elements of the Gothic literary genre; as attendees of October's book club might recognize, Hepzibah and Clifford Pyncheon, molding away in their lugubrious mansion, resemble nothing so much as a parodic version of the sibling tenants of Poe's "House of Usher."

Soon, we moved into the topic of morality. Clifford's languid obsession with the Beautiful provided a fascinating clash with the dynamism and sometimes greedy actions of other characters. Where does virtue lie? The novel does not allow for simplistic moralizing, and that may be what keeps the story interesting (that and the mystery behind the family curse, and the burning question of whether ghosts are lurking in dark corners).

When we tired of intellectual discussion, we proceeded to mock the summary of the novel printed on the back of the nefarious POD edition. Here's where some of the silliness led us:

"...the tenants of the many-gabled house...what? Many-gabled? Are you serious?"

**pause**

"...Multi-gabled!"

"Poly-gabled."

And the clear winner:

"#that'ssogabled"

If you want in on this fun, please do join us for January's book club, taking place on Wednesday the 7th. We will be reading A Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens. A nice, swift read. Festive treats and boozes will be involved. And you don't even need to read the book.

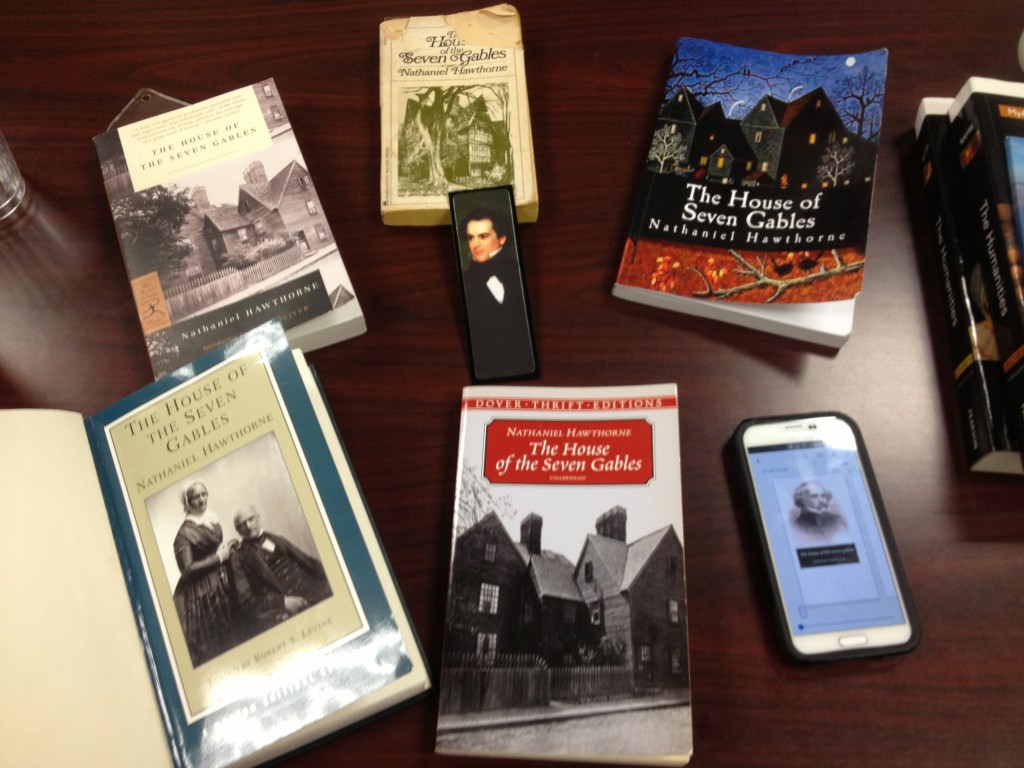

Rare sighting of Stephanie Nelson!

Homer is known to CC 101 students as the author of the Odyssey, but surprisingly enough, not much more is known about his life story. Even his place of birth and gender are a mystery to us.

Homer is known to CC 101 students as the author of the Odyssey, but surprisingly enough, not much more is known about his life story. Even his place of birth and gender are a mystery to us.