Remember the Quebec student protests of two years ago? Those students were protesting the rise of their tuition from $2,168 to $3,793. This seems almost ridiculous to us at the Core office. Our tuition has been raised that much almost every year that we have studied here to increase our tuition from roughly $54,000 (with room and board) to $58,000 this year. How do the majority of us pay for this increase in tuition? Federal student loans, one of the few ways many of us can afford college.

Student loans seem like a wonderful government program at the outset. The government, the institution we, newly 18 Americans, can now elect, helping us immediately achieve the education that has been glorified by our high school guidance counselors for the past four years. There's a darker side though. These loans, according to this Rolling Stones article, could be crippling us as much the lack of a college education could leaving us with tens of thousands of dollars of debt for...what? Fancy dorms? 3-star dining halls? A gym, an olympic sized pool, celebrity professors who teach one, maybe two classes a semester, and constant new construction projects as colleges and universities compete to attract the most students for the upcoming years. Where will these debts leave us? Other students who have already graduated paint a dismal picture. Most of them can't pay the money they borrowed to pay for college:

The Chronicle of Higher Education charges that the government "vastly undercounts defaults." In 2010, it estimated that one in five had defaulted on their loans since 1995, that 31 percent of community-college students default and that an astonishing 40 percent of students attending for-profit schools end up defaulting. A report by the Inspector General of the Department of Education has come to similar conclusions about the reliability of the absurd and arbitrary "cohort" figure.

And a government that has almost complete power to exact these loans from us:

"Student-loan debt collectors have power that would make a mobster envious" is how Sen. Elizabeth Warren put it. Collectors can garnish everything from wages to tax returns to Social Security payments to, yes, disability checks. Debtors can also be barred from the military, lose professional licenses and suffer other consequences no private lender could possibly throw at a borrower.

To many, it seems that the large amount of debt and lack of jobs due to horrible credit makes college unnecessary at best, hurtful at worst to a whole population of middle and low-income class students attempting to make a better life for themselves. Yet, it seems we are stuck between a rock and a hard place:

There's a particularly dark twist to the education story, which is tied to the collapse of the middle class...: College degrees are actually considered to be more essential than ever. The New York Times did a story earlier this year declaring the college degree to be the "new high school diploma," describing it as essentially a minimum job requirement. They found an Atlanta law firm that requires even clerks, secretaries and runners to have four-year degrees and cited research that everyone from hygienists to cargo agents needs to have graduated from college to get hired.

Because of the poor job market, young people may have less of a chance than ever to actually get a good job commensurate with their education. If they don't have the degree, then they have no chance at all. So if they even want a clerking job, they must dive face-first into the debt muck and take their chances that they won't end up watching the federal government take bites out of disability checks while their law degree gathers dust downstairs somewhere. So, yes, a college education is a great thing, and you probably need one now more than ever – the problem is that it may very well be mandatory, may have less of a chance of ever getting you a job, and you may still be paying for it on your deathbed no matter what.

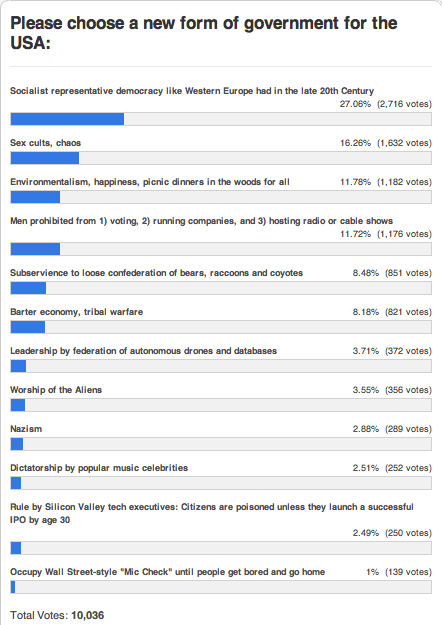

It seems that this year has prompted very little love for our new government. Despite the recent elections and the popularity of Obama that allowed him to be re-elected only a year ago, recent developments from the discovery of the NSA to the weeks long government shutdown, nothing seems to be going right up on Capital Hill.

Yet perhaps students should have been running to the streets earlier, bemoaning the loans that not only forces them into a slave-like relationship with their own elected officials, but also can ruin their life by accruing credit debt beyond what a normal person could ever accumulate in their life time for a degree that can only maybe lead them to a job.

So what do you think? Is college, even at its increasing costs, still necessary for everyone, or does something have to be done, now, about the rising tuition and federal student loan interest? Let us know in the comment.