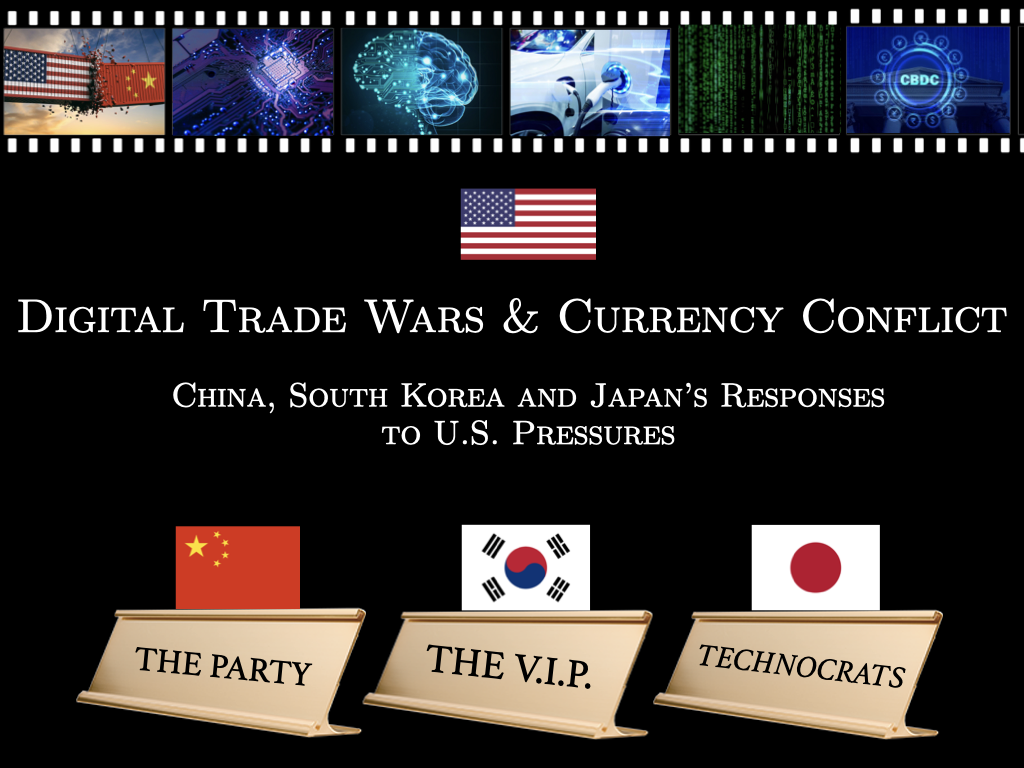

Why do China, South Korea and Japan respond differently to U.S. Pressures in the Digital Economy?

Imagine a world of full connectivity and digitization – realized by AI-driven technology that continues to upscale, amid geopolitical tensions around the globe. In the age of AI, countries around the world would be vying for supremacy in AI with the 5Cs of emerging technologies: cables,chips, (connected) cars, clouds, and coins. Digitization was accelerated and supply chains highlighted in the pandemic – the world witnessed a global chip shortage and vaccine development, amid the boom and bust of crypto and the move toward sovereign digital currencies. Towards the end of the pandemic, emerging technologies had become the centerpiece of geoeconomics, and digitization was taken to the next level with the advent of generative AI. As the AI revolution progresses, the digital economy is expanding rapidly.

Amid such transition, the return to industrial policy by the U.S. has compelled East Asian economies to react, but in different manner to the pressures from the U.S. in the domains of digital trade and finance. During the COVID-19 pandemic, supply chain disruptions prompted the U.S. to engage in de-coupling or de-risking from China – specifically on chips. The global chip shortage prompted the U.S. to onshore chip manufacturing via the Chips & Science Act, which has sparked a subsidy competition for foundries amid a series of sweeping semiconductor export controls by the Bureau of Industry and Security at the U.S. Department of Commerce. China’s ascendance in EVs and batteries has compelled the U.S. to up its game in renewables via the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) subsidies for EVs and batteries. U.S. industrial policy on chips and EVs are now compounded with a preemptive 50% tariff on Chinese chips and 100% tariffs on Chinese EVs, when they have not even entered the U.S. market. On cloud learning at data centers enabled by AI, the U.S. is preparing ‘know-your-customer’ regulations to cloud services to block foreign usage of GPU clusters to train large AI models. Such digital trade wars are ongoing in the absence of a functioning regulatory body (as the WTO DSB has come to a standstill), while digital currency conflict is on the rise as several central banks around the world examine the potential of a CBDC to go cashless amid the volatility of cryptocurrencies.

The tech war combined with the trade war reveals that efficiency based on interdependence no longer holds and that self-sufficiency is crucial persisting geopolitical risk and fragmentation. Countries are now left scrambling to find their positions in the supply chain for survival. At such a pivotal point of digital transformation toward realizing seamless AI, this book aims to explain the reasons as to why China, South Korea and Japan’s responses to U.S. pressures are systematically different. This book argues that the East Asian states’ responses have not been uniform, not merely owing to the geopolitical underpinnings of the bilateral relationships, but because of the institutional variance in policymaking on digital transformation in each jurisdiction. For the longest time, bilateral security alliances were the basis of gauging policy responses from U.S. trading partners in times of U.S. economic pressures. This book offers an alternative narrative of governance by institutions and technological capacity that is wielded as policy leverage, and suggests a triangular framework – a nexus of ‘industry–state–bureaucracy’ – for predicting state responses by a three-step process:

- Industrial Capacity: assessing industrial rigor and competitiveness via technological capacity in each critical sector amid industrial policy (5G/6G, semiconductors, EVs and batteries for connected cars, cloud infrastructure for AI/ML, and digital currencies);

- Policymaking Structure: deciphering post-industrial state-business relations per critical sector in the digital economy;

- Policy Preference: identifying the dominant decisionmaker on the digital economy based on the levels of executive and bureaucratic autonomy and unlocking its policy preference.

Through the empirical findings and analysis using the institutional framework, this book finds that China has retaliated (against the U.S.), South Korea has hedged (between the U.S. and China), and Japan has followed the U.S. upon pressures from the U.S. in the digital economy. It argues that the varied responses can be attributed to the gaps in industrial capacity for emerging technologies toward digitization, coupled with the enmeshed government and business interest in the digital economy. Avid readers of technology who are eager to find out about the inside mechanisms of East Asian tech policymaking from a comparative perspective will benefit from this book, as this book will provide the means of policy projection when looking at geoeconomics conflicts in the digital realm into the future.

This book manuscript is supported by the Individual Impact Grant for 2022 International Strategy Forum (ISF) Fellows by Schmidt Futures (G-22-63371) and has been enriched by the 2019-2020 Next Generation Researchers Grant of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2019S1A5B5A07106479).

Chapter 0. |

PREFACE: Digital Trade Wars and Currency Conflicts in the AI Revolution U.S.-China Trade Wars continued: From Trump to Biden Ecosystems of the Digital Future: Cables, Chips, Cars, Clouds and Coins Why East Asian Economies are Not the Same: Tech Gaps & Policymaking |

Chapter 1. |

INTRO: The U.S. Plays the Same Game in Tech Two Elephants in the Ring: The U.S. and China for AI Supremacy The Puzzle: Why do they respond differently? Policy Relevance: Why this matters Argument: The Nexus of ‘Industry-State-Bureaucracy-Industry’ for AI Research Design, Data and Methodology Contributions Outline of the Book |

Chapter 2. |

HISTORY: How the Old, the New, and the Final Target came to Respond Pressures Remodeled: 'America First' & ‘Made in America’ U.S. Dominant Players in Trade Wars and Currency Conflict The Recurring Cycles of Pressures and Responses The Old Target Responds: Japan The New Target Responds: South Korea The Final Target Responds: China |

Chapter 3. |

STAKES: Inside Today’s Tech Wars on the Path to Digitization

U.S. Pressures toward AI: Tech War and Trade War Combined

The Digital Future and 5Cs of AI: Cables, Chips, Cars, Clouds and Coins

Cables: 5G/6G Connectivity by Antennas & Undersea Cables

Chips: From CPUs and GPUs to NPUs

Cars: EVs & Batteries, ADAS & FSD

Clouds: Data Centers for LLMs of Sovereign AI

Coins: Crypto, Stablecoins and CBDCs

|

Chapter 4. |

ARGUMENT: The ‘Industry-State-Bureaucracy’ Nexus Theorizing Institutional Variance in Responses to Pressures Limitations of Existing Explanations on Responses to Pressures The ‘Industry-State-Bureaucracy’ Nexus for Future Industries Industry: Capacity in High-Tech toward AI State: The Executive’s AI Policy Drive Bureaucracy: The Interlocutor between Industry and State |

Chapter 5. |

RESPONSES: Varying Degrees in Responses to Pressures China: "Retaliate" China's Industrial Capacity for AI - Leader in 5G/6G, AI, EVs & Batteries, Clouds, e-CNY - Leaper in Chip Design & Foundries - Seeker in Advanced Chips China's 'Industry-State-Bureaucracy' Nexus: Centralized - State Control of Industry - Authoritarian System for Indigenous Innovation - Empowered Bureaucracy China's Policy Preference: Escalation - Party Secretary and Premier - Politburo and Committees (CFEAC & CNSC) - MOC, MOF and PBOC South Korea: "Hedge" South Korea's Industrial Capacity for AI - Leader in 5G/6G, Foundry & Memory Chips, Blockchains - Leaper in AI, EVs & Batteries - Seeker in AI Chip Design South Korea's 'Industry-State-Bureaucracy' Nexus: Hybrid - Industry Bargains with State - Presidential System in a Post-Industrial Economy - Subservient Bureaucracy South Korea's Policy Preference: Balancing Act - The V.I.P. - Presidential Aides & METI, MOSF, and the BOK - Industry-State-Bureaucracy Committees Japan: "Follow" Japan's Industrial Capacity for AI - Leader in Materials - Leaper in Robotics - Seeker in Foundry Japan's 'Industry-State-Bureaucracy' Nexus: Technocratic - Industry at Arm's Length from the State - Parliamentary System in a Contracting Economy - Dualistic Bureaucracy Japan's Policy Preference: Adherence - MOF & METI, and the BOJ - Zoku - PM and his Cabinet |

Chapter 6. |

CASES: Digital Trade Wars

Cables

Pressures: U.S. Huawei Ban and Open-RAN

Responses: China - Huawei’s Lead in 5G/6G Patents and Global Expansion

South Korea - 5G Commercialization and 6G Readiness

Japan - Attempts at 6G

Chips

Pressures: U.S. Export Controls, Subsidies, Investment Screening

Responses: China - The Revitalization of Huawei X SMIC

South Korea - Samsung vs. TSMC, Fabs in U.S. & China

Japan - TSMC in Kumamoto for Sony, Rapidus in Hokkaido

Cars

Pressures: U.S. EV Subsidies and Tariffs

Responses: China - BYD Overtaking Tesla, CATL in the lead

South Korea - SK ON & LG Energy Solutions X U.S. Autos

Japan - Late in the EVs & Batteries Game, Toyota X Panasonic

Cloud

Pressures: AWS, Microsoft Azure & Google Demand Market Access

Responses: China - Huawei, Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu vs. AWS

South Korea - Naver, KT (Public) vs. U.S. Players (Private)

Japan - Public & Private Clouds dominated by U.S. Players

|

Chapter 7. |

CASES: Digital Currency Wars

Coins: DeFi (Cryptocurrencies/Stablecoins) vs. CeFi (CBDCs)

Pressures: The Fed’s Big Steps, Strong Dollar amid Inflation

SEC's Crypto Crackdown, Divided Views on CBDCs

Responses: China - Voiding Crypto, PBOC's e-CNY for De-dollarization

South Korea - Regulating Crypto, BOK's CBDC Pilots

Japan - Vibrant Crypto Market, BOJ's Delayed CBDC Pilots

|

Chapter 8. |

TAKEAWAYS: The ‘So What?’ Question Recognizing the New Normal of Tech Wars and Trade Wars Combined Utilizing the ‘Industry-State-Bureaucracy’ Nexus as Policy Predictor Strategies for the Future based on Anticipated Responses |

Chapter 9. |

CONCLUSION: It’s ‘Who Has’ and ‘Who Decides’. The U.S. is no longer No.1 in Everything China, South Korea and Japan have Tech Gaps Alliances Still Matter but Capacity Matters More |