This week’s collection of links explores Don Quixote, Big Foot, William Shakespeare and Jane Austen (at the same time), and more!

- The Boston Public Library is celebrating the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death with two art exhibitions. The first, entitled “Shakespeare’s Here and Everywhere,” (open until Feb. 26 in the Leventhal Map Center) highlights vintage maps associated with the bard and his plays. The second show, “Shakespeare Unauthorized” (running through March 31 in the McKim Exhibition Hall) takes a look at the BPL’s Shakespeare collection. More information may be found in the Core office.

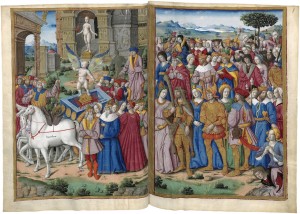

- It’s a big year for 400th anniversaries. Cervantes celebrates the big 4-0-0 (since his death, of course) this year alongside Shakespeare. In celebration, it seems that a Disney adaptation of Don Quixote is in the works.

Honor Daumier, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza (ca. 1850). Black crayon and wash, 16 x 22 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- Hieronymus Bosch’s c. 1500 work Garden of Earthy Delights, a triptych depicting the marriage of Adam and Eve, a grotesque Godless world, and a scene of eternal damnation that would make Dante jealous, has taken the fashion world by storm.

- Atlantic writer Edward links the frequency of Big Foot sightings across cultures to Enkidu, Esau, Rousseau’s noble savage, and Caliban from Shakespeare’s The Tempest. In other words, we’re pretty sure we stumbled upon a Core scholar.

- Will & Jane: Shakespeare, Austen and the Cult of Celebrity, an exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library of Washington, D.C., examines the similarities in the cultural stardom of Jane Austen and Shakespeare. It closes this Sunday, November 6.

- London-based theater company Border Crossings and the Palestinian ASHTAR Theatre present Ilium and Ithaka – Plays of Love and War: This Flesh is Mine and When Nobody Returns, retellings of The Iliad and the Odyssey set in the Middle East.

Photo: The Flesh Is Mine, by Jamie Wiseman.

That’s it for this week’s links! Let us know if you spot any Core-related news or cultural events by emailing core@bu.edu.