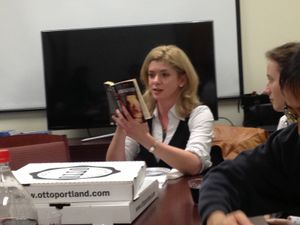

Big turn-out this month: EnCore book club members met to discuss the much-beloved Gothic novel Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, written by Mary Shelley.

Big turn-out this month: EnCore book club members met to discuss the much-beloved Gothic novel Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, written by Mary Shelley.

The discussion began with the novel's framing device. The story begins with an exchange of letters between Captain Robert Walton and his sister. The captain, on an expedition to the North Pole, meets with Victor Frankenstein, a broken man on a journey to destroy a creature he brought to life using unspeakable secrets of science. The rest should be familiar to many readers/horror fans. These opening letters are a Gothic device meant to give a veneer of plausibility to otherwise extraordinary events.

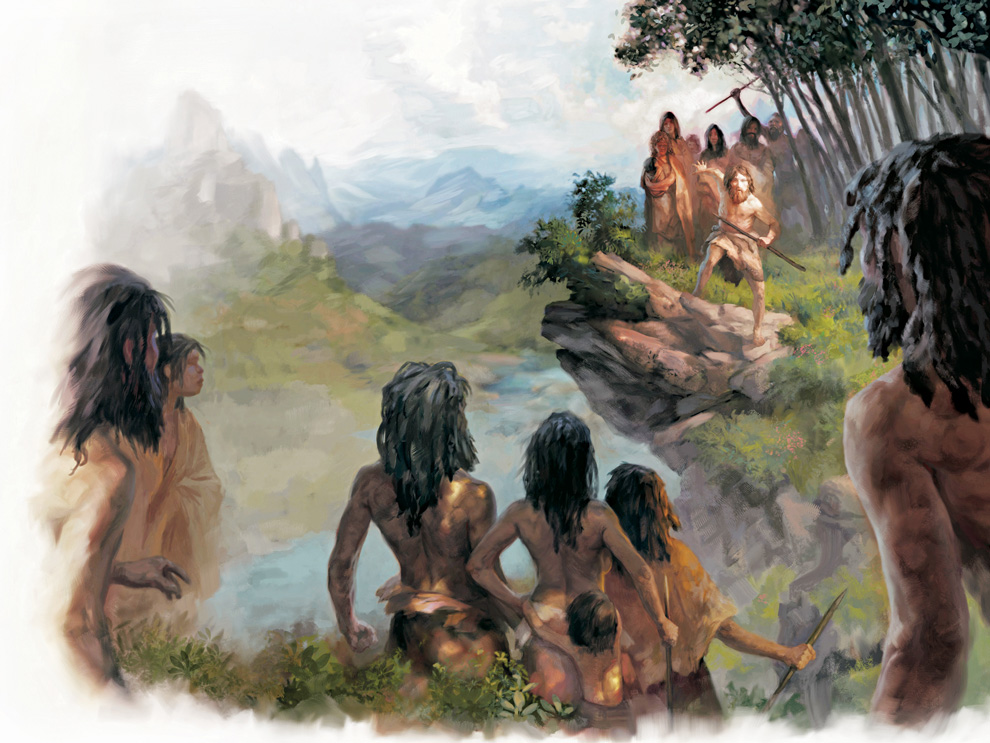

Attendees discussed the Romantic influences at work in the story: the majesty of nature and its terrifying power, the consequences of stepping beyond the bounds of human ability, and the inevitable comeuppance that will follow he who does not know his limits.

"Why do we like the Gothic? Why do we like scary things?" "Cos our lives don't have danger anymore." "Have you SEEN the MBTA?"

We also discussed why we enjoy works that make us afraid, make us feel revulsion, make us weep. Is it because we no longer fear for our lives on a regular basis, and we are searching for a stimulus? What is more fearful: explicit gore, or what our imagination produces? The violence in Frankenstein is much more muted than that which 21st century horror films often provide for us. Is what we're afraid of so different from what terrorized the Victorians?

We can all agree that what is truly terrifying is not the creature's crimes, but rather Victor's inability to empathize with the living being he has created. The creature has feelings, language, can walk...who is truly the inhuman one?

In his attempt to stop death, Victor succeeds in producing life, but what a life.

"There is a serious birth control message in this book."

Hilarious, but true: the novel clearly warns against producing life in non-Christian-sanctioned ways, and the Bride of Frankenstein never comes to be due to Victor's fear the two monsters will choose to populate the world with horrid spawn. Clearly, Victorian men know best how to control women's bodies.

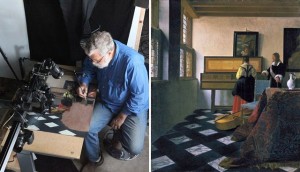

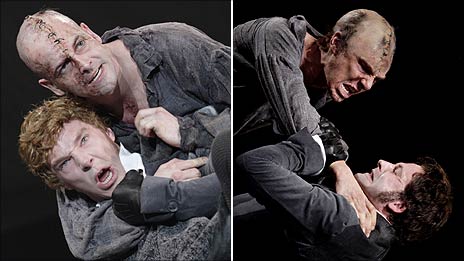

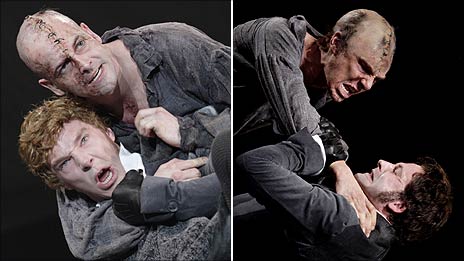

The themes of dehumanization and defilement are manifold. Perhaps this explains why, in the incredibly popular UK National Theatre stage adaptation of the play, directed by Danny Boyle, starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Johnny Lee Miller alternating in the scientist/monster roles, Elizabeth, Victor's bride-to-be, is not only murdered by the creature, but is also raped. He defiles and destroys her as completely as Victor desecrates and destroys his second creation.

Benedict Cumberbatch and Johnny Lee Miller alternating roles in Frankenstein.

In the end, it is hard to say who exactly is the monster. It must be no coincidence most people erroneously believe the creature's name is Frankenstein.

Sorry you missed out on the discussion? Join us at our next meeting: on December 4th, we will be meeting in the Core office to discuss J. R. R. Tolkien's The Hobbit. If you are of age, BYOB, and there will be free food for all!

Memorable Quotes from the evening:

"Who has done that? Who has put organs together to make a live thing?" "I have!"

[In discussing the onstage violence in King Lear] "When your eye is being plucked out, I'm sure you'd be smelling his hand and thinking 'That guy uses Dial.'"

Best line of the evening? Core's new motto, in light of Victor's attempt to have a more, shall we say, complete education:

"Read the books. Come to class. Don't destroy mankind."