December 1, 2010 at 6:07 pm

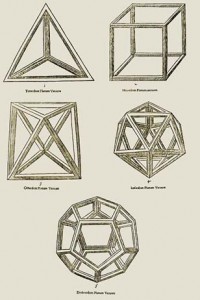

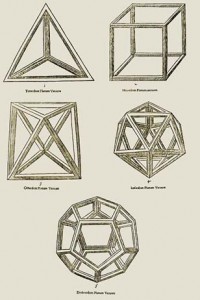

CC101 students, please be reminded that you are meeting for lecture at 9:30 AM tomorrow in the Tsai Auditorium for the second and final forays into the world of Greek (and contemporary) mathematics. Prof. Hall’s lecture tomorrow will be on the nature of mathematical proof, with an example from Platonic solids. Current students can view his lecture handout here.

Above: One of Leonardi da Vinci's drawings of the five Platonic solids

By CAS Core Curriculum

|

Posted in General Announcements

|

Tagged C101, lectures, math

|

December 1, 2010 at 5:19 pm

Je ne dirai rien de la philosophie, sinon que, voyant qu'elle a été cultivée par les plus excellents esprits qui aient vécu depuis plusieurs siècles, et que néanmoins il ne s'y trouve encore aucune chose dont on ne dispute, et par conséquent qui ne soit douteuse, je n'avois point assez de présomption pour espérer d'y rencontrer mieux que les autres; et que, considérant combien il peut y avoir de diverses opinions touchant une même matière, qui soient soutenues par des gens doctes, sans qu'il y en puisse avoir jamais plus d'une seule qui soit vraie, je réputois presque pour faux tout ce qui n'étoit que vraisemblable.

I will say nothing of philosophy except that it has been studied for many centuries by the most outstanding minds without having produced anything which is not in dispute and consequently doubtful 'and uncertain'. I did not have enough presumption to hope to succeed better than the others; and when I noticed how many different opinions learned men may hold on the same subject, despite the fact that no more than one of them can ever be right, I resolved to consider almost as false any opinion which was merely plausible.

-- René Descartes, in his Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One's Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences, 1637. The English text above -- suggested for today's analect by Kalani Ho McDaniel (Core '10, CAS '12) -- is taken from the translation by Laurence Lafleur used in CC201. The French text may be found online at Project Gutenberg.

By CAS Core Curriculum

|

Posted in Analects

|

Tagged analect, CC201, Descartes, philosophy, proof, truth

|

December 1, 2010 at 12:51 pm

Additional messages came in over the weekend from alumni who wish to express their condolences to the friends and family of Professor James Devlin, and to share memories of having him as a teacher and a friend.

- Dr. Devlin is an unforgettable man. As an 18-year old student sitting in his CC101, I found him to be both terrifying and inspirational as I listened to him talk about everything under the sun for 3 straight hours. Nearly 20 years later, I continue to think of him as one of the most influential people in my life, and I have yet to encounter a more passionate, enthralling lecturer. I am truly honored to have had him as a professor.

-- Cheryl Rosenberg (née Gonda), CAS '96

- I'm saddened to learn of the passing of our dear Professor Devlin. My deepest condolences. May his inspiration and leadership live on through the Core community past, present, and future.

-- Ryan Ives, CAS '00

By CAS Core Curriculum

|

Posted in Great Personalities

|

Tagged alumni, faculty, in memoriam, memories

|

November 30, 2010 at 5:52 pm

In a narrow circuit strait'n'd by a Foe,

Subtle or violent, we not endu'd

Single with like defence, wherever met,

How are we happy, still in fear of harm?

But harm preceeds not sin: only our Foe

Tempting affronts us with his foul esteem

Of our integrity

Today's analect -- suggested by Sarah Cole (Core '10, CAS '12) is taken from Milton's Paradise Lost, lines 323-29 (Eve addressing Adam), edited by Prof. Christopher Ricks, whose lecture last week for CC201 was received with great enthusiasm. Students or alumni who wish to borrow a recording of the talk may sign out a VHS in the Core office.

By CAS Core Curriculum

|

Posted in Analects

|

Tagged CC201, milton, Ricks

|

November 30, 2010 at 5:29 pm

You can’t become a good writer by watching YouTube, texting and e-mailing a bunch of abbreviations.

-- Marcia Blondel, a teacher of English at Woodside High School in California, as quoted in "Growing Up Digital, Wired for Distraction," one in a series of articles The New York Times is publishing in order to explore how "a deluge of data can affect the way people think and behave." The author of the article, Matt Richtel, summarizes the strain on students' attention as an overabundance of choices: "Computer or homework? Immediate gratification or investing in the future?"

By CAS Core Curriculum

|

Posted in Future of the Book, Great Questions

|

November 30, 2010 at 4:39 pm

The Times Literary Supplement recently addressed how people are often mislead into thinking Jonathan Swift presents a negative view of human nature in Gulliver's Travels, a book read in the second year of the Core Humanities:

Yet what readers tend also to be told is that the moral system of Houyhnhnms, according to which no value is to be attached to personal affections, and death, whether that of others or one’s own, should not be the occasion of any emotion, represents Swift’s notion of an ideal civilization. Gulliver’s account is perfectly explicit.

"They [the Houyhnhnms] have no Fondness for their Colts or Foles; but the Care they take in educating them proceedeth entirely from the Dictates of Reason. And I observed my Master [a dapple-grey horse] to shew the same Affection to his Neighbour’s issue that he had for his own. They will have it that Nature teaches them to love whole Species, and it is Reason only that maketh a Distinction of Persons, where there is a superior Degree of Virtue . . . . If they can avoid Casualties, they die only of old Age, and are buried in the obscurest Place that can be found, their Friends and Relations expressing neither Joy nor Grief at their Departure, nor does the dying Person discover the least Regret that he is leaving the World."

That Swift means us to regard the Houyhnhnms as an ideal contrast to the wayward or sinful behavior of ordinary humanity is plainly false – indeed, frankly, rather absurd. The sooner a reader has cleared his (or her) mind of this idea the better; for it obscures the function that Swift has, in fact, and most ingeniously, assigned to the Houyhnhnms in his scheme. What he presents us with in his Houyhnhnms is an only slightly exaggerated version of the outlook of an early eighteenth-century Deist or devotee of Nature and Reason; and the point that his narrative is making, with steadily increasing force, is that, for a fallible and unwary mortal like Gulliver (or ourselves) an encounter with such rationalizing and Pharisaic doctrines could have a quite lethal effect on our character.

Care to offer an opinion? Is Swift really giving the reader a warning about rampant misanthropy rather than presenting a version of it himself? Feel free to leave a comment elaborating on your perspective, or discuss it on the EnCore Facebook page.

By CAS Core Curriculum

|

Posted in Core Authors

|

Tagged CC202, Swift

|

November 29, 2010 at 4:42 pm

Tomorrow afternoon, the students of CC201 will attend a lecture by Prof. Michael Zell on the art of Dutch master Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn. In acknowledgment of this artful inclusion of painting in the second-year Humanities, today's Analect -- suggested by Tom Farndon (Core '10, CAS '12) -- is an image rather than a text quote.

(Self-portrait at the age of 34, by Rembrandt, 1640, oil on canvas, 102 x 80 cm, National Gallery, London.) Tom writes: "Rembrandt was very well known for his etchings, but even more so for his devotion to portraying a true interpretation of himself in his self-portraits, avoiding vanity and exaggeration. See more examples of his work and find a directory of museum holdings at RembrandtPainting.net, a clearing house of information about the artist maintained by independent art historian Jonathan Janson."

By CAS Core Curriculum

|

Posted in Analects, Art

|

Tagged CC201, painting, Rembrandt

|

November 29, 2010 at 10:49 am

Core Lectures this week:

CC101: Professor Hall on Plato and a Math Education 11/30

CC101: Professor Hall on Proofs 12/2 (note second lecture this week! In Tsai from 9:30-11)

CC105: Professor Faul on Plate Tectonics 11/30

CC105: Professor Faul on The Earth's Oceans 12/2

CC201: Professor Zell on Rembrandt van Rijn 11/30

CC203: Professor Shipton on Exchange and Reciprocity 12/2

Watch for the final exam schedule to be listed next week.

This Week

- Tuesday, November 30. The Core Film Series presents Good Will Hunting. See Boston circa 1997, and how math is cool!Free pizza. Screening in the Core House, 141 Carlton Street. All are welcome. See a trailer at YouTube.

- Wednesday, December 1. The EnCore Book Club meeting to to discuss Siddhartha. 6-8 PM in the Alumni Lounge, 595 Commonwealth Avenue, West Entrance, 7th Floor. RSVP at the Facebook event page.

Core Stuff:

- Do you want to improve your writing? Core writing tutors are available in CAS 129 M-F 10-1 and from 2-4; sign up for an appointment in CAS 119.

- CC105 walk-in tutoring occurs every Monday, 3-5 PM in the Core office with ERC tutor John McCargar.

Get connected with Core!

Do you have any ideas, or comments about Core activities? Email Professor Kyna Hamill.

By CAS Core Curriculum

|

Posted in e-bulletin

|

Tagged e-bulletin

|

November 24, 2010 at 5:11 pm

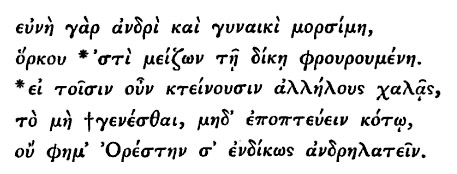

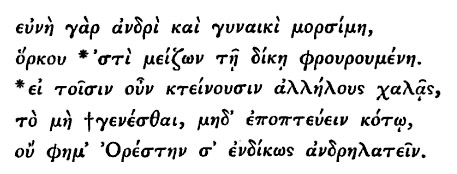

Marriage of man and wife is Fate itself,

stronger than oaths, and Justice guards its life.

But if one destroys the other and you relent --

no revenge, not a glance in anger -- then

I say your manhunt of Orestes is unjust.

-- Apollo addressing the Leader, in Aeschylus's Eumenides, the final play in his Oresteia trilogy (from the translation for Penguin by Robert Fagles, p.240, lines 215-19)

By CAS Core Curriculum

|

Posted in Analects

|

Tagged Aeschylus, Analects, CC101, justice, Oresteia

|

November 23, 2010 at 3:48 pm

Prof. Christopher Ricks lectured today for the students of CC201, on the subject of the John Milton. He is the author of Milton's Grand Style (Oxford University Press, 1978). In the spring semester, he often lectures on the English Romantic poets. Students, with their Kerberos password, can access his packet of selected readings here. Today's analect is drawn from his study of one of those poets, his book Keats and Embarrassment, published by Oxford University Press in 1974:

Embarrassment can be an antagonist whom even love may sometimes succumb to fearing: this seems to me a perceptive and seldom said. It is not only those who suffer from ereuthophobia, a morbid propensity to blush or to fear blushing, who should acknowledge this. The difference is the size of the self-recognition in Keats, and this has its bearing on the odd relationship of embarrassability to empathy. [page 24]

Ricks and other scholars participated in a panel discussion, sponsored by the Keats-Shelley Association of America, following a special screening of the movie Bright Star, based on events in the life of Romantic poet John Keats. An audio recording of that discussion is hosted by the Romantic Circles blog, and can be downloaded as an mp3. He also wrote in response to this film for the New York Review of Books.

An interview with Prof. Ricks can be found here, as published in the Spring 2010 issue of the Core Journal. In another interview, conducted by Sally Mapstone in Hilary Term 2009, and published in the second issue of the newsletter for the English faculty at Oxford, Prof. Ricks addresses the bothersome convention which separates poetry and prose into distinct categories of accomplishment:

When it comes to the lectures given by a Professor of Poetry, you can't expect people to do any specific reading in advance, so naturally enough the lectures tend to concentrate on short poems. (Not that all short poems are lyrics.) So I think that there are distortions of literature, and of thinking about literature, that come from having a Professor of Poetry, and poets have on the whole colluded with this flattery. I think that it’s wrong – this was the subject of my first lecture – simply wrong of Coleridge to enjoin the distinction that he made: prose is the words in the best order, poetry is the best words in the best order. Shakespeare never wrote better (better words in a better order) than when he wrote the great sequence 'Hath not a Jew eyes?' And there is the supreme prose of Hamlet to Horatio before the duel, and of Edmund on astrology. As to the related question of whether the Professor of Poetry has to be himself or herself a poet, I’d like to think that if there were a Professor of Prose, there wouldn’t be the assumption that it would have to be a novelist, say, as against a philosopher, historian, or John Maynard Keynes. I’m very much in favour of the holder’s often being, perhaps almost always being, a practising (as they say) poet, but this isn’t without its own difficulties or pressures. Granted, there have been many great poet-critics, and this Chair [of Professor of Poetry at Oxford] has enjoyed more than its share of them. But then there was Tennyson, and there was Hardy, and William Barnes, none of whom wished to be a critic and whose poetry in a way depends on their not being.

By CAS Core Curriculum

|

Posted in Academics

|

Tagged CC201, Keats, poetry, Ricks, Romantics

|