It’s hard to believe fifteen years have passed since the release of the original Toy Story. I was four when it came out, and all I remember from that first screening is being absolutely terrified by some of the damaged toys. Of course, now that film is more remembered for introducing the public to the style of animation that now dominates the weekly box office and to the studio that so defines that style that their releases have become yearly national events: Pixar. No studio has ever had a role like that, and now, fifteen years and eleven films later, Pixar has looked back to its beginnings to craft its greatest work to date, Toy Story 3. Now, to be perfectly honest, Pixar’s great track record aside, I was worried that this would be another cheap cash-in sequel from Disney, and while it doesn’t cover much ground that they haven’t hit before, it covers it better in almost every way. Toy Story 3 is funnier and more moving than anything Disney has ever released, and in terms of animation, it probably falls just short of the magnificent Wall-E, but is still near the top of the Pixar cannon.

It’s hard to believe fifteen years have passed since the release of the original Toy Story. I was four when it came out, and all I remember from that first screening is being absolutely terrified by some of the damaged toys. Of course, now that film is more remembered for introducing the public to the style of animation that now dominates the weekly box office and to the studio that so defines that style that their releases have become yearly national events: Pixar. No studio has ever had a role like that, and now, fifteen years and eleven films later, Pixar has looked back to its beginnings to craft its greatest work to date, Toy Story 3. Now, to be perfectly honest, Pixar’s great track record aside, I was worried that this would be another cheap cash-in sequel from Disney, and while it doesn’t cover much ground that they haven’t hit before, it covers it better in almost every way. Toy Story 3 is funnier and more moving than anything Disney has ever released, and in terms of animation, it probably falls just short of the magnificent Wall-E, but is still near the top of the Pixar cannon.

This second sequel takes place ten years after the end of 1999’s Toy Story 2, with Andy on his way to college and Woody, Buzz and the rest of the toys facing a crossroads. Only the core group from the first two remains, with the rest having been broken or given away over time, and while Andy wants to take Woody with him, he decides to leave the rest of his toys behind in the attic (which is probably for the best, I can’t imagine someone with that many toys in his dorm doing too well in college), but a misunderstanding almost leads them to the dump and, angry with Andy for nearly throwing them away, Buzz, Jessie, the Potatoheads, Slink, Rex, Hamm, Bullseye and Barbie decide to donate themselves to a day care center. Woody follows and tries to convince them otherwise, but once they arrive, the group is convinced to stay by the leaders of the toys there, Lots-O’-Huggin’ Bear and Ken (Ned Beaty and Michael Keaton respectively). Woody tries to go home, but the others stay behind and discover that the leaders are sacrificing them to be played with by the youngest children there, who have a shocking ability to cruelly break everything. Once Woody discovers the truth, he has to rescue his friends and get back to Andy before college.

Now, if you’ve seen the first two, this plot should sound at least vaguely familiar, but, as I said, that’s not really the point. Sure the admittedly predictable plot can be a bit annoying and there have been other animated films that deal with growing up and moving on with life, but none have done it with such humor and emotion. After Up, which I found to be incredibly unfunny, I was worried that this type of humor wouldn’t appeal to me anymore, but no, the jokes just had to be funny. A much higher percentage of the humor in Toy Story 3 is aimed at the adults in the audience than the children, and I really think that this film will have the most appeal to people like me who saw the first film as a child. The smaller cast allows for much more character development, especially of the human characters, which has never been Pixar’s strength. Thankfully, the characters they kept are all voiced by very funny actors (with a possible exception for Joan Cusack’s Jessie, who I’ve always found to be somewhat grating), and the writing has matured over time, so the one-liners can just flow from all over the screen. Unlike Toy Story 2, where many of the new characters didn’t really work, the latest additions to the toy line, especially Ken, are all quite humorous, and the new cast members fit in perfectly. Aside from Beatty and Keaton, who are both fantastic, Timothy Dalton, Jeff Garlin, Whoppi Goldberg and Richard Kind all join the cast in smaller roles. The smaller cast also allows it to reach a greater emotional depth, especially during the film’s final moments, which are easily the most moving scenes in any Pixar film. For the first time that I can recall in a Disney release, there is an actual sense of danger and excitement, and even though you know everyone is going to be OK in the end, there will be moments where you’re so lost in the story that you just can’t be sure. I would also like to point out that the requisite short film attached to the beginning, “Day and Night,” is the strongest Pixar short that I can recall, both in terms of story and animation, and that alone makes the 3-D upgrade nearly worth it. Thankfully, unlike Disney’s last 3D release, the dreadful Alice In Wonderland, Toy Story 3 was meant to be seen with that extra dimension, and the upgrade is handled with much class and subtlety. Nothing pops at you, but the greater amount of depth to the story is reflected by the greater amount of depth and detail on screen.

It was obvious from the trailers that this film would be less risky than the last three from the studio—Ratatouille’s basic premise seemed like it would turn off some viewers, people though Wall-E’s silent first half and anti-consumerist environmental message would anger much of the audience and Up’s more mature subject matter, dealing with death, made it seem less likely to succeed with children—and I’m worried that some will see this as a regression for the studio. So now I think it’s time to remind everyone that you can’t look at a studio in terms of Auteurism. I know I can be guilty of it, but, high artistic ambition aside, Pixar is a business above all else, albeit an extremely successful one. This is the first film Lee Unkrich has ever directed (he edited the previous two in the series), and he can’t be judged according to the studio’s prior releases, even if their worst film (Cars) is still noticeably better than anything rival Dreamworks Animation has ever released. Even with the core group of John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton, Brad Bird and Pete Docter involved somehow in every project, every director brings their own stamp to the work. In Unkrich’s case, it’s an evolved focus on a sort of realism, with more natural colors and many shots showing just how small the toys are in the world, a perspective that was missing from the last two. On the other hand, it’s probably for the best that we treat some sort of animation that way. Until American audiences can accept animation as a legitimate medium and not something just meant for kids and so-called “family” movies, the best stuff will continue to come from Japan and other countries that are using it correctly (I would consider Richard Linklater’s two great rotoscoped films to be their own in-between medium). So no, Toy Story 3 isn’t quite as great as Hayao Miyazaki’s masterworks, but it is the closest I’ve ever seen an American animated film get to that level.

-Adam Burnstine

Toy Story 3 is rated G.

The film opens everywhere, including Imax, on June 18th.

Directed by Lee Unkrich; written by Lee Unkrich, John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton and Michael Arndt; original music by Randy Newman; directing animator, Michael Stocker; produced by Darla K. Anderson and John Lasseter; distributed by Walt Disney Studios. Running time: 1 Hour 49 minutes.

With: Tom Hanks (Woody), Tim Allen (Buzz), Joan Cusack (Jessie), Ned Beaty (Lost-O’-Huggin’ Bear), Don Rickles (Mr. Potato Head), Michael Keaton (Ken), Estelle Harris (Mrs. Potato Head), Wallace Shawn (Rex), John Ratzenberger (Hamm) and John Morris (Andy).

After watching Bigger than Life in all of its glorious, controlled, expansive, vibrant, claustrophobic, screaming Cinemascope glory I watched it again.

After watching Bigger than Life in all of its glorious, controlled, expansive, vibrant, claustrophobic, screaming Cinemascope glory I watched it again. It’s hard to believe fifteen years have passed since the release of the original Toy Story. I was four when it came out, and all I remember from that first screening is being absolutely terrified by some of the damaged toys. Of course, now that film is more remembered for introducing the public to the style of animation that now dominates the weekly box office and to the studio that so defines that style that their releases have become yearly national events: Pixar. No studio has ever had a role like that, and now, fifteen years and eleven films later, Pixar has looked back to its beginnings to craft its greatest work to date, Toy Story 3. Now, to be perfectly honest, Pixar’s great track record aside, I was worried that this would be another cheap cash-in sequel from Disney, and while it doesn’t cover much ground that they haven’t hit before, it covers it better in almost every way. Toy Story 3 is funnier and more moving than anything Disney has ever released, and in terms of animation, it probably falls just short of the magnificent Wall-E, but is still near the top of the Pixar cannon.

It’s hard to believe fifteen years have passed since the release of the original Toy Story. I was four when it came out, and all I remember from that first screening is being absolutely terrified by some of the damaged toys. Of course, now that film is more remembered for introducing the public to the style of animation that now dominates the weekly box office and to the studio that so defines that style that their releases have become yearly national events: Pixar. No studio has ever had a role like that, and now, fifteen years and eleven films later, Pixar has looked back to its beginnings to craft its greatest work to date, Toy Story 3. Now, to be perfectly honest, Pixar’s great track record aside, I was worried that this would be another cheap cash-in sequel from Disney, and while it doesn’t cover much ground that they haven’t hit before, it covers it better in almost every way. Toy Story 3 is funnier and more moving than anything Disney has ever released, and in terms of animation, it probably falls just short of the magnificent Wall-E, but is still near the top of the Pixar cannon. You know, I really wanted M. Night Shyamalan’s The Last Airbender to be good. It’s been too long since the last good fantasy action movie that I was willing to try to go easy on it because it’s a kid’s film and there’s no fun in trashing Shyamalan for his decade-long losing streak anymore, and I tried to like it, I really did. Kids and adults both seem to really love “Avatar: The Last Airbender,” the Nickelodian show on which the film is based (I assume you can guess why they had to drop the “Avatar” part), so I had hope for the story, and there was no way he’d be able to throw a pointless twist onto part one of an already written trilogy. I was right about that second part by the way, but to go easy on this film would be a disservice. You see, it turns out that Shyamalan’s ineptitude as a writer extends beyond the ends of his films. The Last Airbender isn’t poorly written like, say, The A-Team, just to name another bad summer movie, no, this one is more in line with The Room. In fact, the idea that someone read this script and said “sure, here’s three hundred million dollars,” makes pretty much the same amount of sense as someone reading The Room and saying “sure, here’s six million dollars.” At least the second financer here may have seen the comic value in Tommy Wiseau’s cult hit. People have always said that Shyamalan is a better director than a writer, but whatever hope I had for an aesthetically pleasing film went out the door the second it was converted to 3D. This is by far the worst use I’ve seen of the new technology, although, to be fair, as far as I could tell, the only time the audience in the screening reacted to anything was to laugh at the general laziness of the 3D.

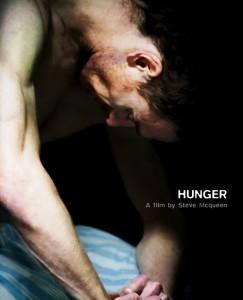

You know, I really wanted M. Night Shyamalan’s The Last Airbender to be good. It’s been too long since the last good fantasy action movie that I was willing to try to go easy on it because it’s a kid’s film and there’s no fun in trashing Shyamalan for his decade-long losing streak anymore, and I tried to like it, I really did. Kids and adults both seem to really love “Avatar: The Last Airbender,” the Nickelodian show on which the film is based (I assume you can guess why they had to drop the “Avatar” part), so I had hope for the story, and there was no way he’d be able to throw a pointless twist onto part one of an already written trilogy. I was right about that second part by the way, but to go easy on this film would be a disservice. You see, it turns out that Shyamalan’s ineptitude as a writer extends beyond the ends of his films. The Last Airbender isn’t poorly written like, say, The A-Team, just to name another bad summer movie, no, this one is more in line with The Room. In fact, the idea that someone read this script and said “sure, here’s three hundred million dollars,” makes pretty much the same amount of sense as someone reading The Room and saying “sure, here’s six million dollars.” At least the second financer here may have seen the comic value in Tommy Wiseau’s cult hit. People have always said that Shyamalan is a better director than a writer, but whatever hope I had for an aesthetically pleasing film went out the door the second it was converted to 3D. This is by far the worst use I’ve seen of the new technology, although, to be fair, as far as I could tell, the only time the audience in the screening reacted to anything was to laugh at the general laziness of the 3D. There is a man lurched forward. His shirt is off, but his striped blue and white pants radiate in the background. The man’s face is emaciated but his expression is without pain or happiness. Where his skin isn’t stained red from blood or bruising, it is a bland pale white. This image is featured on the cover of one of Criterion’s latest release, the 2008 film Hunger. The man is Irish Republican Army member Bobby Sands (Michael Fassbender) during his (in)famous hunger strike in 1981 as shown in Steve “not that one” McQueen’s debut masterpiece.

There is a man lurched forward. His shirt is off, but his striped blue and white pants radiate in the background. The man’s face is emaciated but his expression is without pain or happiness. Where his skin isn’t stained red from blood or bruising, it is a bland pale white. This image is featured on the cover of one of Criterion’s latest release, the 2008 film Hunger. The man is Irish Republican Army member Bobby Sands (Michael Fassbender) during his (in)famous hunger strike in 1981 as shown in Steve “not that one” McQueen’s debut masterpiece. Photography and cinema, Siegfried Kracauer observed, have a special power to portray happenstance. Often films, trying to use this power, spoil the effect with a certain portentousness: see Crash or the execrable 13 Conversations About One Thing. People encounter one another haphazardly, but random luck sends them in directions already meticulously charted: Initial conflict! Reluctant interpersonal perestroika! Self-discovery! Highly engineered “chance” and transparent moral messages tend to combine rather fretfully. The big problem is that “random encounters can affect people” is not a compelling insight, and seems only present as an excuse for Hollywood’s over-rationalized psychology of human connection.

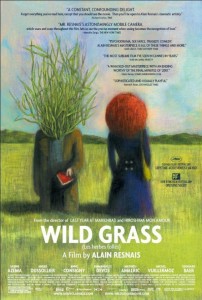

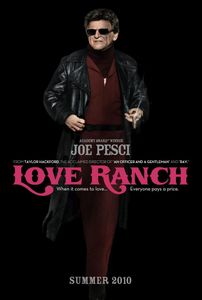

Photography and cinema, Siegfried Kracauer observed, have a special power to portray happenstance. Often films, trying to use this power, spoil the effect with a certain portentousness: see Crash or the execrable 13 Conversations About One Thing. People encounter one another haphazardly, but random luck sends them in directions already meticulously charted: Initial conflict! Reluctant interpersonal perestroika! Self-discovery! Highly engineered “chance” and transparent moral messages tend to combine rather fretfully. The big problem is that “random encounters can affect people” is not a compelling insight, and seems only present as an excuse for Hollywood’s over-rationalized psychology of human connection. How many times have we seen this picture of the modern American West: kitschy, raunchy cities naïvely clinging on the edge of enormous, bare landscapes? The backdrop of Taylor Hackford’s Love Ranch is not unique in the movies; Nevada and California’s mountains and canyons, juxtaposed with a protagonist’s capitalist hubris, make for an instantly recognizable theme: the futility of trying to control one’s fate when the world is so unforgiving. But if Love Ranch, written by Mark Jacobson, starts off in this well-explored territory, some narratives are worth repeating--especially when the main character is not the little man fighting destiny, but this vain American dreamer’s tragically resigned, clear-sighted wife.

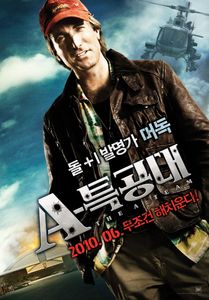

How many times have we seen this picture of the modern American West: kitschy, raunchy cities naïvely clinging on the edge of enormous, bare landscapes? The backdrop of Taylor Hackford’s Love Ranch is not unique in the movies; Nevada and California’s mountains and canyons, juxtaposed with a protagonist’s capitalist hubris, make for an instantly recognizable theme: the futility of trying to control one’s fate when the world is so unforgiving. But if Love Ranch, written by Mark Jacobson, starts off in this well-explored territory, some narratives are worth repeating--especially when the main character is not the little man fighting destiny, but this vain American dreamer’s tragically resigned, clear-sighted wife. I think I’ve only seen one episode of “The A-Team,” but thanks to the show’s comically strict adherence to formula and more than two decades of parody since its cancellation, I think I do get the general idea. Maybe if I was older, I’d be able to enjoy the show for some nostalgic purpose, but alas, I cannot, and am thus left with absolutely no reason to enjoy it. Conveniently, “absolutely no reason to enjoy it” is also a pretty good way of summing up my thoughts on Joe Carnahan’s big-budget remake of the show, which comes out this week. It seems difficult, but the creators of this origin story have failed in a way that even the worst recent superhero origin stories basically succeed: they forgot to actually create characters. Forget that this is an idiotic, aesthetically inept production that is chock full of poor dialogue, inept and possibly dangerous morals and no real plot to speak of, those are simply the problems of most Hollywood action movies, The A-Team goes a step further by actually ignoring character development and anything even resembling a story arc for any of its characters. The film covers a nearly nine-year span, and during that time, there is not a single instance of development or permanent change in any of its major characters. The actors at least kind of try, but there is no overcoming a script which is nothing except nearly two hours of setup punctuated by the occasional flash of rather dull action.

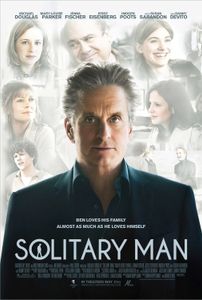

I think I’ve only seen one episode of “The A-Team,” but thanks to the show’s comically strict adherence to formula and more than two decades of parody since its cancellation, I think I do get the general idea. Maybe if I was older, I’d be able to enjoy the show for some nostalgic purpose, but alas, I cannot, and am thus left with absolutely no reason to enjoy it. Conveniently, “absolutely no reason to enjoy it” is also a pretty good way of summing up my thoughts on Joe Carnahan’s big-budget remake of the show, which comes out this week. It seems difficult, but the creators of this origin story have failed in a way that even the worst recent superhero origin stories basically succeed: they forgot to actually create characters. Forget that this is an idiotic, aesthetically inept production that is chock full of poor dialogue, inept and possibly dangerous morals and no real plot to speak of, those are simply the problems of most Hollywood action movies, The A-Team goes a step further by actually ignoring character development and anything even resembling a story arc for any of its characters. The film covers a nearly nine-year span, and during that time, there is not a single instance of development or permanent change in any of its major characters. The actors at least kind of try, but there is no overcoming a script which is nothing except nearly two hours of setup punctuated by the occasional flash of rather dull action. The title "Solitary Man" sounds a bit like "A Serious Man," but the two movies are polar opposites. Whereas the Coen brothers' film is about a good man struggling to keep his life in balance, the 2009 film by Brian Koppelman and David Levien concerns a bad man resolutely tearing his life apart. More importantly, A Serious Man is odd, scary, and philosophically ambitious; Solitary Man seeks nothing better than to titillate people who find Michael Douglas totally fascinating. If this sounds like an exaggeration, go see the film and count how many monologues the script spoon-feeds its star. Consider the midfilm monologue, delivered to the unfortunate Jesse Eisenberg, that begins something like "Lemme tell you a story" and then continues for a good two minutes without a single cutaway for relief. Eisenberg may have been grateful for the lack of a reaction shot, which would have forced him to feign interest. In that sense, he's luckier than Susan Sarandon, Danny Devito and all the other co-stars crammed into the film just to ask Douglas helpful questions.

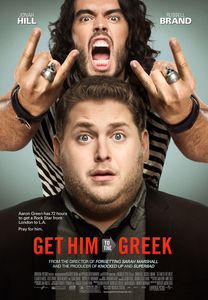

The title "Solitary Man" sounds a bit like "A Serious Man," but the two movies are polar opposites. Whereas the Coen brothers' film is about a good man struggling to keep his life in balance, the 2009 film by Brian Koppelman and David Levien concerns a bad man resolutely tearing his life apart. More importantly, A Serious Man is odd, scary, and philosophically ambitious; Solitary Man seeks nothing better than to titillate people who find Michael Douglas totally fascinating. If this sounds like an exaggeration, go see the film and count how many monologues the script spoon-feeds its star. Consider the midfilm monologue, delivered to the unfortunate Jesse Eisenberg, that begins something like "Lemme tell you a story" and then continues for a good two minutes without a single cutaway for relief. Eisenberg may have been grateful for the lack of a reaction shot, which would have forced him to feign interest. In that sense, he's luckier than Susan Sarandon, Danny Devito and all the other co-stars crammed into the film just to ask Douglas helpful questions. The premise is a simple one, one likely heard many a time during the endless bombardment of commercials: a record company employee must get a rock star to the Greek Theater in 72 hours. However, producer Judd Apatow has built his career by taking these simple stories, mixing in some raunchy humor, adding a moral, and turning them into comedic and box office gold. Get Him to the Greek is no exception.

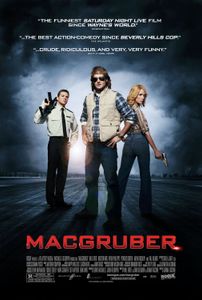

The premise is a simple one, one likely heard many a time during the endless bombardment of commercials: a record company employee must get a rock star to the Greek Theater in 72 hours. However, producer Judd Apatow has built his career by taking these simple stories, mixing in some raunchy humor, adding a moral, and turning them into comedic and box office gold. Get Him to the Greek is no exception. One of the few good aspects of Saturday Night Live’s long, slow descent into complete irrelevance has been the lack of any films based on the venerable show’s sketches. After eleven releases between 1990 and 2000, of which only Wayne’s World even approached watchability, there were none in the last decade. Jorma Taccone’s Macgruber is proof that this was probably for the best. Basing a film on a mediocre recurring sketch from a now irrelevant TV series that satires a TV series that has been off the air since 1992 never seemed like the best idea, but even I was shocked by how awful the film really was. Macgruber is not simply unfunny; it actually lacks almost anything that I could actually think of as an attempt at a joke.

One of the few good aspects of Saturday Night Live’s long, slow descent into complete irrelevance has been the lack of any films based on the venerable show’s sketches. After eleven releases between 1990 and 2000, of which only Wayne’s World even approached watchability, there were none in the last decade. Jorma Taccone’s Macgruber is proof that this was probably for the best. Basing a film on a mediocre recurring sketch from a now irrelevant TV series that satires a TV series that has been off the air since 1992 never seemed like the best idea, but even I was shocked by how awful the film really was. Macgruber is not simply unfunny; it actually lacks almost anything that I could actually think of as an attempt at a joke.