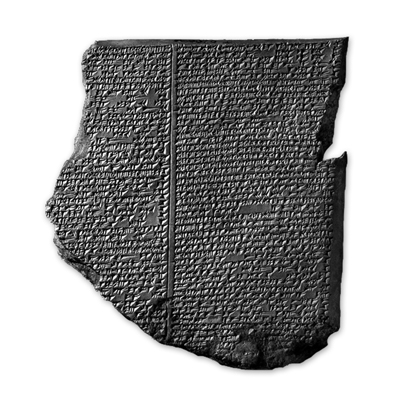

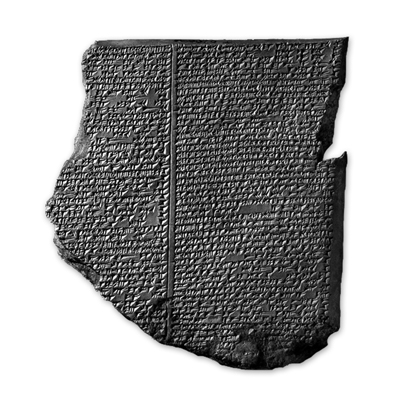

The Flood Tablet, relating part of the Epic of Gilgamesh

To inaugurate the launch of the Core blog, Prof. David Eckel—Director of the Core Curriculum—conducted an interview with respected author and translator David Ferry, whose poetic rendering of Gilgamesh is the first book read by students in Core Humanities. This is the second half of that interview.

[... in continuation of the interview from yesterday's post... ]

David Eckel: Many students are puzzled by the text’s approach to sexuality. It is hard to know, in the case of Shamhat, the temple prostitute, whether we should admire her or fear her. The same could also be said about the goddess Ishtar. Could you give us any guidance about how to interpret these figures?

David Ferry: I don’t see how any issues of admiration or fear come up about the temple prostitute. She’s sent on a sexual mission. She invites the wild man, who is more animal than not, into a week of sexual intercourse that, along with beer and cooked food, brings him into human or more human, identity and human culture. She invites him to Uruk and his service to human beings, his love for Gilgamesh, and ultimately his fate. But I don’t see that there are issues of our response to her as a character. She’s an agent, with a religious function of seduction. Ishtar of course, we do fear. But there are other words to use about her, for example in the great comic but also dire scene where she hits on Gilgamesh, and then in her interview with her father god Anu. What does one make of her in the Flood, where she seems contrite. She’s the goddess of love, the goddess of taverns, the goddess of lots of things. Complex in the way Venus is in the Aeneid, Aphrodite in the Iliad, and in the ways that Juno (Hera) and Minerva (Athena) are. Admiration, well, yes, fear, certainly, uncertainty, certainly. Too many possible words to use to describe how we take her in our experience of the poem.

DE: When we last spoke about the Epic, you said that its account of the Flood seemed more convincing to you than the account in the book of Genesis. What did you have in mind?

DF: I don’t know that I said “convincing.” I do think the narrative, the telling of the story, is thrilling detailed beyond the telling of the story in the Hebrew version; especially as preceded by the story of how Utnapishtim is taught by the god Ea to deceive his doomed townspeople. I think. The Hebrew telling has nothing like those tears running down the sides of Utnapishtim’s nose. I’m just a reader. I have no right to interpret the differences between the two great tellings. If the criterion is justice, the Hebrew tale seems much more coherent to me. The Flood is a punishment of men for their bad conduct and Noah is saved because of his virtue. (I know this is an oversimplification). In Gilgamesh (and in the Sumerian flood story that precedes it) the Flood is a flood and the gods are bewildering (and themselves somewhat bewildered). There isn’t a clear justice pattern. But there is questioning of the gods, not stated directly but involved in the very telling. Both are convincing, which is to say, we recognize their relevance to what happens to us in our lives. But so different.

DE: In the text of the Epic, Gilgamesh fails in his quest for immortality. But the story of Gilgamesh is as close to immortal as any text in the literature of the world. Why do you suppose the Epic has had such enduring significance, not just in Mesopotamia but in the rest of the world?

DF: It’s hard to answer this. It appears in different versions in several languages, in ancient times. On the other hand, since it was only discovered for us in the nineteenth century it came close to not being immortal. On the other hand it’s enduring significance is, I guess, in the great political and moral lesson it teaches: immortality is unavailable to us human beings; we are going to die; we need to define ourselves and our behavior, within the constraints of that knowledge. I think the “intention” of the poem was to teach something like that, politically and morally. But of course that’s an oversimplification. It’s also, for example, a great enduring love story, between Gilgamesh and Enkidu, comparable to the love between David and Jonathan, Achilles and Patroclus. The vocabulary, in the Gilgamesh telling, is in some ways maybe more particularly sexual. I think one of the lessons of the poem, along with the teaching about the acceptance of the constraints of mortality, is there in “Two people, companions, they can prevail.” They don’t prevail, but the love story is a great, beautiful, enduring example.

Do you have your own questions for David Ferry? Core students and alumni are invited to email their inquiries to Core, to be forwarded to Prof. Ferry and answered in a follow-up post next week.

Related links:

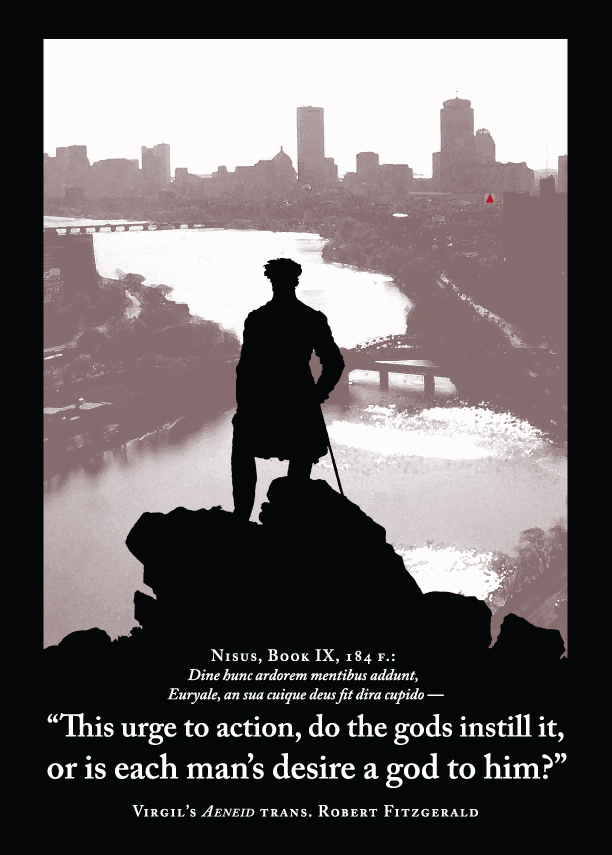

This image and quote appeared on the back of the Spring 2010 Core tee-shirt

This image and quote appeared on the back of the Spring 2010 Core tee-shirt