This post was originally created in February; due to some sort of glitch, the original post has been deleted and replaced with this one. No changes have been made to the content.

Fiction alum Patricia Park (Fiction ’09)’s debut young adult novel, Imposter Syndrome and Other Confessions of Alejandra Kim, was released by Crown Books for Young Readers on February 23! To celebrate the book’s release, current program administrator Annaka Saari (Poetry ’21) was able to interview Patricia about the novel via email.

Annaka Saari: Imposter Syndrome and Other Confessions of Alejandra Kim is your debut Young Adult novel. How was the process of writing this book different (if at all) than the way that you approach writing novels targeted toward adult readers?

Patricia Park: I love the freshness of voice and raw honesty in YA fiction. So I made specific craft choices, e.g., first person POV, present verb tense—to convey the intimacy and immediacy of an experience, unfolding in real time.

In adult fiction, young protagonists are written with the benefit and maturity of adult hindsight; you can employ the retrospective narrator that contextualizes the gap between the lived experience and the reflection after. But you lose some of that immediacy of the experience.

AS: Both Imposter Syndrome and Other Confessions of Alejandra Kim and your first novel, Re Jane, focus on characters who inhabit a variety of identities. Ale, the protagonist of Imposter Syndrome, is both Latinx and Korean; she spends the majority of her time between her mostly-white high school and her more diverse neighborhood. How was the process of fleshing out such a complex character, and did you run into any unexpected challenges while honing her voice?

PP: I write about minorities within minorities—specifically within the Korean American identity. We contain multitudes! With Ale, my challenge was to both get a 17 year-old’s voice down, as well as to understand Argentine Spanish, which is heavily Italian-influenced. Prior to this project, I knew both Spanish and Italian. But I taught myself Argentine slang and studied with Argentine professors at Middlebury College’s Summer Language Institute (the one where you have to take a pledge not to read, write, speak, or listen to any other language but Spanish!). I did a several research trips to Argentina, where I attended churches, worked in businesses, and interviewed members of the Korean Argentine community, including my own family members.

The worst thing you can do with a teen character is talk down to them—or to your audience. So I’d do the kinds of writing exercises I do with my MFA students at American University—writing diary entries, poking in their fridges and school bags, writing from the character’s viewpoint at different ages of their life (childhood to adulthood). You learn to adjust their syntax and diction with each stage of the character’s life.

AS: Geography is an important facet of your novels – both Imposter Syndrome and Other Confessions of Alejandra Kim and Re Jane are set in Queens, New York (with much of Re Jane taking place in Seoul, South Korea as well) and place is clearly a lens through which your protagonists consider their own identities. What’s it like to create characters that are emotionally and otherwise anchored in specific locations?

PP: Queens stories are overlooked and untold. We’re a literal pitstop in literature, a “valley of ashes”—as anyone whose read their Gatsby knows! Yet Queens is the most ethnically diverse place in the world, with over 300 languages spoken. I was born and bred in Queens, and I am absolutely shaped by my geography. Richard Russo has a great craft essay on setting called, “Location, Location, Location,” which I teach to my students all the time. Russo talks about the importance of not giving the “tourist” version of a place; it should be real, emotionally honest, and embedded in character (I’m paraphrasing). If I just gave readers the Times Square version of New York, I could never live with myself.

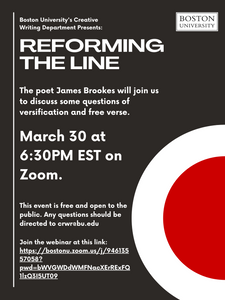

Tonight at 6:30PM, the poet James Brookes (Poetry '21) will join us (via Zoom webinar) for a discussion of versification and free verse poetry. James will begin by lecturing on the subject but will then take questions from the audience.

Tonight at 6:30PM, the poet James Brookes (Poetry '21) will join us (via Zoom webinar) for a discussion of versification and free verse poetry. James will begin by lecturing on the subject but will then take questions from the audience.